Spawn in Hollywood

Or…How A Now Barely Watchable Movie Made Comic Book and Hollywood History: Part One

Spawn in Hollywood

(This is the first entry in a series looking at how Todd McFarlane changed how Hollywood approached comic book creators when it came to making movies from their creations. And, before you scoff, trust me, he did change things for the better. There’ll be more, a lot more, to come)

Rob Liefeld had led the way when it came to negotiating with Hollywood from Image, selling several properties to various Hollywood studios. He managed to convince Steven Spielberg and Dreamworks studio to buy his Dooms IV concept, before the comic book existed.

Liefeld and Image were new, fresh, and insanely popular with young people. They led the comic book market, selling millions of comics and products. It wasn’t hard to see why Hollywood saw the attraction. It became somewhat of a running joke after Image got up and running – Rob wakes up, thinks of a name for a comic book, calls his agent, sets up a meeting, sells the name, goes to sleep a million dollars richer. Wash, rinse and repeat.

Money for nothing really.

No matter how many concepts Liefeld sold, and he sold a lot, the movies weren’t forthcoming. It would take McFarlane to lead the way and get the first Image related movie into the marketplace.

McFarlane had been shopping Spawn around since he launched it in 1992. Once Hollywood began to hear McFarlane bragging about how many Spawn comics he had sold, how many it was selling per month, their interest was piqued. Studios came calling, all wanting to get in on the action. They thought they’d be dealing with an idiot who drew comic books. A kid, ripe for plucking. Someone who’d freak out at the sight of a check with six figures in it.

How wrong they were. Todd McFarlane, along with Liefeld, Jim Lee, Valentino, Erik Larsen and the rest of Image had all grown up learning the lessons of Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and more. They’d heard the horror stories and seen how it all ended when you signed over your creations. They knew how people had died in poverty, forgotten by an industry that spat people out and left them to fend for themselves while the companies sought out the Next Big Thing.

They weren’t going to let that happen to anyone at Image, that much was for sure. If they wanted Spawn, then they’d have to agree to McFarlane’s terms, not the other way around. This wasn’t how things in Hollywood were done, especially when it came to comic books.

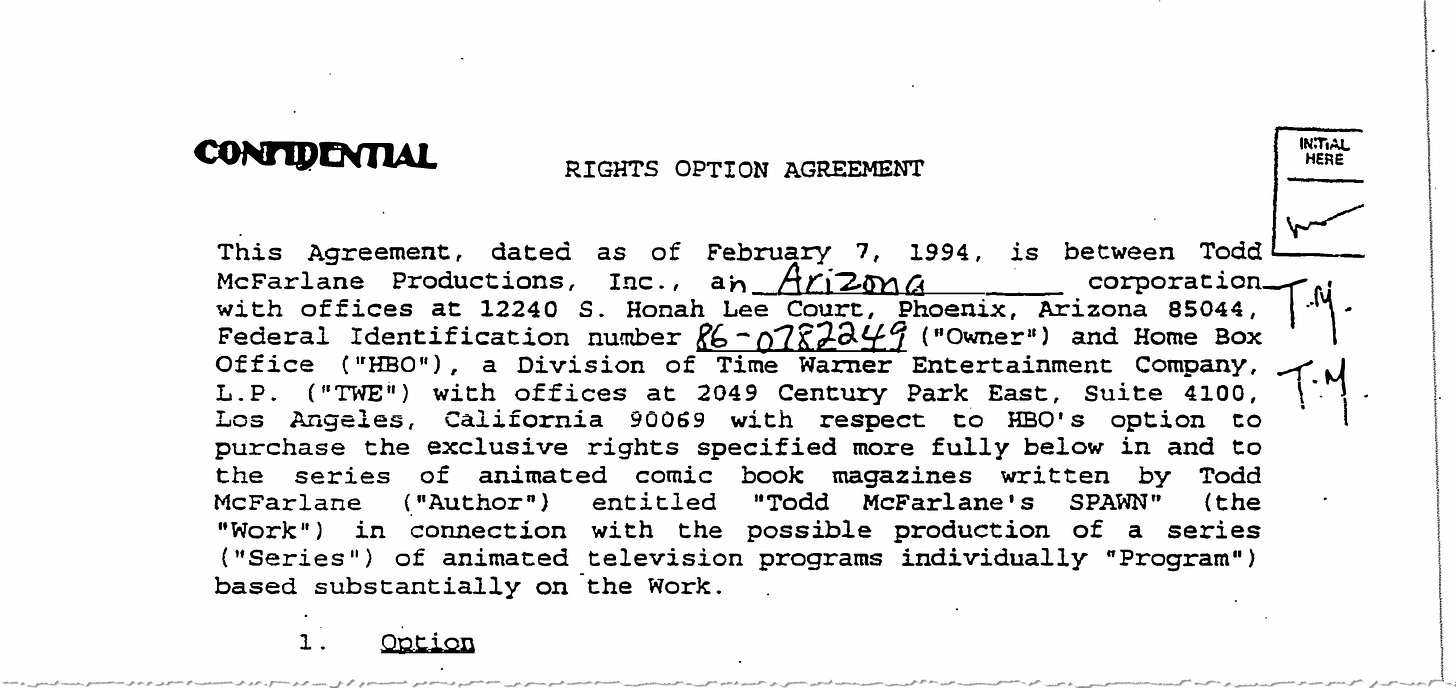

McFarlane entered negotiations with HBO in 1994 for an animated Spawn TV series. By October 1995 the contracts had been signed and production started on the animated series in early 1996.

McFarlane drove a hard bargain. It wasn’t enough to see Spawn on TV, he wanted to see his name up there in lights. After all, it wasn’t Mickey Mouse, it was Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse. It was Stan Lee Presents. It simply had to be Todd McFarlane’s Spawn.

The contracts showed that each episode of the animated series was to be called ‘Todd McFarlane’s Spawn’, albeit with the name ‘Spawn’ in larger type than McFarlane’s name, and it was also made clear that all characters and concepts in the series would be, ‘Based Upon Characters Created by Todd McFarlane’. Much like the Uslan/Swamp Thing contract, these characters would include anything created for the Spawn universe by others, such as Neil Gaiman.

This was just one clause that would come back to haunt McFarlane, along with another indemnifying HBO from any potential damages if a lawsuit was filed against them, say, for example, for the use of a name that might cause angst. Another unique aspect of the HBO series was the presence of McFarlane himself. He would physically appear on screen, introducing each episode.

One non-negotiable for McFarlane, as with anything he signed related to Spawn, was that the character was issued on license. Nobody, other than McFarlane would be able to claim ownership or control of Spawn.

The animated Spawn series made its debut on American television on March 27, 1997. It became a hit and would run for three seasons, winning an Emmy Award in 1999 (its last season) for Outstanding Animation Program. Following Spawn would be Erik Larsen and Savage Dragon and Jim Lee’s WildC.A.T.S. Both were picked up for animated series but neither had the same impact as Spawn.

Part of this can be put down to how hands off Larsen and Lee were, compared to how hands on McFarlane was. McFarlane’s contracts called for a level of creative control that he exercised. He wasn’t just prepared to cash the cheques and move on. Spawn had to be done properly, or not at all.

The animated Spawn series would prove to be both a blessing and a curse for McFarlane. It was a blessing as it got Spawn into more households than the comic book ever could, but it was a curse as this is where the mother of hockey player and professional thug Tony Twist saw his namesake. Twist’s mother contacted her son and told him that he was being portrayed as a fat, immoral, murderous, foul-mouthed mobster. Twist tuned in and believed himself slandered, leading to the lawsuit that would see Todd McFarlane Productions being placed into Chapter 11 and costing McFarlane millions over the next decade.

That was in the future. For the time being, the Spawn series was popular enough for Hollywood to take a punt on a film. McFarlane had been holding meetings about the film as early as 1993. As he would later recall,

A lot of Hollywood people approached me about doing Spawn as a movie just because it was the number one book. It was a no-brainer for those people who are paid to buy options. Hollywood is notorious for that. But most of these people hadn't done their homework, they hadn't even seen the book and had no love for it. They figured, well, we made a comic book movie before, we made Batman or Superman or whatever. We'll just plug it into our formula. Ultimately, that was why I felt I had to maintain control of it.[i]

At the same time as McFarlane was establishing his independence in the comic book industry, three employees of Industrial Light and Magic, the firm owned and run by George Lucas, were also breaking away and going it alone.

Mark Dippé, Clint Goldman and Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams had become disillusioned with the lack of recognition and credit afforded to them while working at ILM. While working for Cameron, Dippé and Williams had created some of the more impressive effects for the films The Abyss and Terminator 2. They had also worked on Jurassic Park for Steven Spielberg and designed Jim Carrey’s signature mask for The Mask. But they had zero artistic control. They came up with the ideas and brought them to the screen, but it was the directors who took all the credit.

This was a situation that McFarlane could identify with. Williams was already known to him via Liefeld, and the two had hit it off immediately, bonding over a mutual love of sports. ‘Toddy just wanted mavericks,’ said visual effects supervisor Steven Williams. ‘He was sick of dealing with Hollywood greaseballs. He was totally right about that. We hit it off right away as soon as we learned we were both into hockey.[ii]

I was animation supervisor on Jurassic Park. I guess McFarlane saw it and he was in negotiations with Columbia to do Spawn, his character. And of course, Todd being a Canadian maverick as well didn't want to give up ownership of his character, so he went to New Line. And I had just started a relationship with New Line as visual-effects supervisor for The Mask and they did very well by that. Todd said, ‘Look, I want you and one of my other partners Mark Dippé and another guy named Clint Goldman to produce my movie Spawn for me -- you know, very much in the same kind of effects-driven genre as Jurassic’.[iii]

A meeting was set up between Dippé, Goldman, Williams, and McFarlane and the three men pitched their plans for a Spawn film. McFarlane liked what he heard.

‘We met Todd McFarlane, who had just brought Spawn out to the public and he was interested in making a feature based on his characters,’ Dippé said. ‘Of course, as soon as I read the first few books, I saw the potential of the characters and I enthusiastically jumped aboard. I wrote a story with Todd, which formed the basis of the project, and it went very quickly from there. Initially, I'd just wanted to help him because I liked the book, and Todd's graphic style and storytelling were the best. I liked Todd's attitude, who he is, what he is doing. He is a very talented, bright guy. So, I gave him a few ideas and a month later, he said, ‘You make the movie. Here, it's yours.[iv]’’

McFarlane was still dealing with Columbia and was very close to signing a lucrative deal with the studio. The negotiations always reached a hurdle – Spawn wasn’t for sale, only rent. McFarlane wouldn’t sign away any rights to the character including merchandising.

The first major deal came when Columbia Studios offered to make a Spawn movie with a budget of $100,000,000, using A-List stars and a name director. They offered McFarlane a seven-figure sum to sign on. After months of negotiations between lawyers, a contract was drawn up and sent to McFarlane to sign. He had his legal team go over it. As he went over it McFarlane discovered that, under the terms of the Columbia Studios contract, he would have to surrender all merchandising rights for a Spawn movie and sign away ownership of Spawn for the film medium.

With the contract literally on the table, just waiting for him to sign, reportedly in front of the studio heads, McFarlane got up and walked away, leaving millions of dollars to go begging.

I thought that the bigger the movie got, the more I'd be out of the picture on some level. I'd rather have the opportunity to provide input in a positive way for the character. I see Spawn like a creative child, and I treat him like one of my children. Therefore, the neighbors aren't going to dress my kid, they're not going to adopt him and take away visitation rights. If they get Spawn, they also get the Little League father with him.[v]

Columbia was stunned. This was money he was walking away from. All to retain the rights to a comic book character. And merchandising? Only George Lucas got that clause. And, of course, Walt Disney. And, for all his bluster, Todd McFarlane wasn’t Walt Disney.

McFarlane later explained his reasons for turning down the contract.

To them, it's just another licensing deal with another faceless entity. You make the deal and, next thing you know, these characters have suddenly got talking dogs and spaceships and all this stuff that had nothing whatsoever to do with the original concept. And all because there was nobody around to say, ‘No, that is not what you bought. That is not our character.’ I was like, ‘What, you're gonna make me rich and famous? Too late! You guys got here about five years too late. I don't care if I get to go to a party and meet Demi Moore’.

All I'm interested in is putting a good product on the screen. To me it's just a part of the process of making Spawn a household name. Sure, it might have been a bigger budget with bigger stars and a bigger director, and it might have made 10 times the money our film is going to make. But I never want to be sitting in a theatre, with my dad sitting next to me, and he says, ‘Wow, Todd, that was cool. What did you have to do with it?’ And I have to say to him, ‘Uh, well, I cashed the check.’ I'd rather die.[vi]

Of course, McFarlane didn’t want to meet Demi Moore. He was happily married, another concept that Hollywood has a hard time understanding. After all, didn’t everyone want to meet Demi Moore and perhaps chance their arm (and other appendages) with her? Those at Columbia might have been thinking that they should have offered McFarlane the chance to go to a party and meet Nathan Lane instead.

The next studio to come calling was New Line Cinema, best known for small, low budget films and as a distributor for equally low budget horror movies and independent films. They didn’t have the money to throw around in big advances, but they could offset that liability in other areas.

New Line hit big when they sealed the distribution rights to 1990s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and its sequel. As a studio, they were relegated to making sequels to the Nightmare on Elm Street, Critters and House Party series. The success of these films saw New Line bought by Ted Turner for $500 million in January 1994.

The comic book-based film, The Mask, was distributed by New Line and had proven to be amazingly successful on a small budget. More importantly, Clint Goldman was producing the film, so he had direct access to Mike DeLuca.

‘Mike DeLuca knew about Spawn when nobody else did because it was brand-new,’ Dippé recalled. ‘He said, ‘Spawn?! That's the hottest comic book around.’ He knew even then, before most people had heard of the book, so in that sense he was really with us. It went from there, basically.[vii]‘

With the New Line deal falling into place, McFarlane formed a new company to handle the film and its negotiations, Todd McFarlane Entertainment, and both he and New Line settled down to hammer out a deal that would be beneficial to everyone. Beneficial, for McFarlane, was simple. He would retain full creative control over the film and keep his merchandising rights. In return for these two clauses McFarlane sold the rights to Spawn to New Line Cinema for the bare minimum allowable - $1.

Another Image partner resting at New Line in the mid-1990s was Rob Liefeld. He had signed a deal with the studio to produce adaptations of his Avengelyne and Badrock characters. Liefeld’s contract followed the same terms as the McFarlane deal, with Liefeld’s Extreme Studios to become co-producers of the finished product with New Line.

Liefeld also had deals with Tri-Star Entertainment for Prophet, Dreamworks for Dooms IV and Fox Studios for a Youngblood animated series. Yet another of his projects, The Mark, was sitting at Paramount Studios with Tom Cruise attached.

Unfortunately for Liefeld, although his strike rate of selling properties for film was still batting 100, the production of those films was 0.

NEXT: Preparing Spawn

[i] Aberly, Rachel. (1997, October). The Making of the Movie Spawn.

[ii] The Globe and Mail, 9 Aug 1997

[iii] Canada AM - CTV Television, Toronto, 1 Aug 1997

[iv] Aberly, Rachel. (1997, October). The Making of the Movie Spawn

[v] Ibid

[vi] Toronto Star, 2 Aug 1997

[vii] Aberly, Rachel. (1997, October). The Making of the Movie Spawn

(Text is copyright 2024 Daniel Best and cannot be reproduced or published without express permission)

Discovered this show via HBO recommendations a few months ago. Really exciting to read and can’t wait for the next rendition :)