Norm Breyfogle (Auto)Biography: Indie Artist: 2003 - 2008

"I was thinking about different scenarios where I could burn a number of pages a week or maybe one page a day and the only thing that would save them from the fire would be somebody buying the page."

Indie Artist: 2003 - 2008

Conversation with Norm, plus contributions from Chuck Satterlee.

Even though the door for Marvel and DC had shut, Norm had other options available. Once people discovered his presence (both via the internet and via advertisements that he’d placed in the CBG) he was inundated with requests for commission work, with the bulk of the orders being for Batman. Small press publishers also began to vie for his services, with companies such as Angel Gate, Speakeasy/Markosa, First Salvo and others all lining up and offering Norm the chance to draw both cover and interior art, and in the case of First Salvo and Markosa, launching flagship titles based around Norm as the regular, and in some cases the star, artist.

Daniel: How did Black Tide come about?

Norm: That’s a good question. I haven’t thought about it for so long that I’m drawing a blank! I don’t know. It must have been due to some reference by somebody that I’ve forgotten about now. You could ask Debbie Bishop, the creator, publisher, editor, and writer of Black Tide. It’s amazing I don’t remember, I always remember things like this. For whatever reason, I haven’t filed it in my long term memory, I guess.

Daniel: You once mentioned to me that although it was only five issues, it took you the better part of a year.

Norm: I forgot how many issues there were but yeah. They were longer issues, for one thing, and I was doing the covers, too. There were 26 pages per issue, I think. But the main thing was that Debbie was really particular about the pencils and the inks, particularly the pencils because I don’t really change much in the inking stage. She gave more editorial overview than anybody that I’ve ever worked with before; and I’m not really complaining, they were her characters, she was writing it as well as self-publishing it, and all of her changes made sense, but it did slow the process down a bit.

Daniel: They were full pencils that you had to submit to them, as opposed to your usual breakdowns and the preliminaries that you did.

Norm: I believe they were drawn 8 x 11, so they were halfway between my typical roughs and my complete pencils. They qualified as full pencils but they weren’t full size.

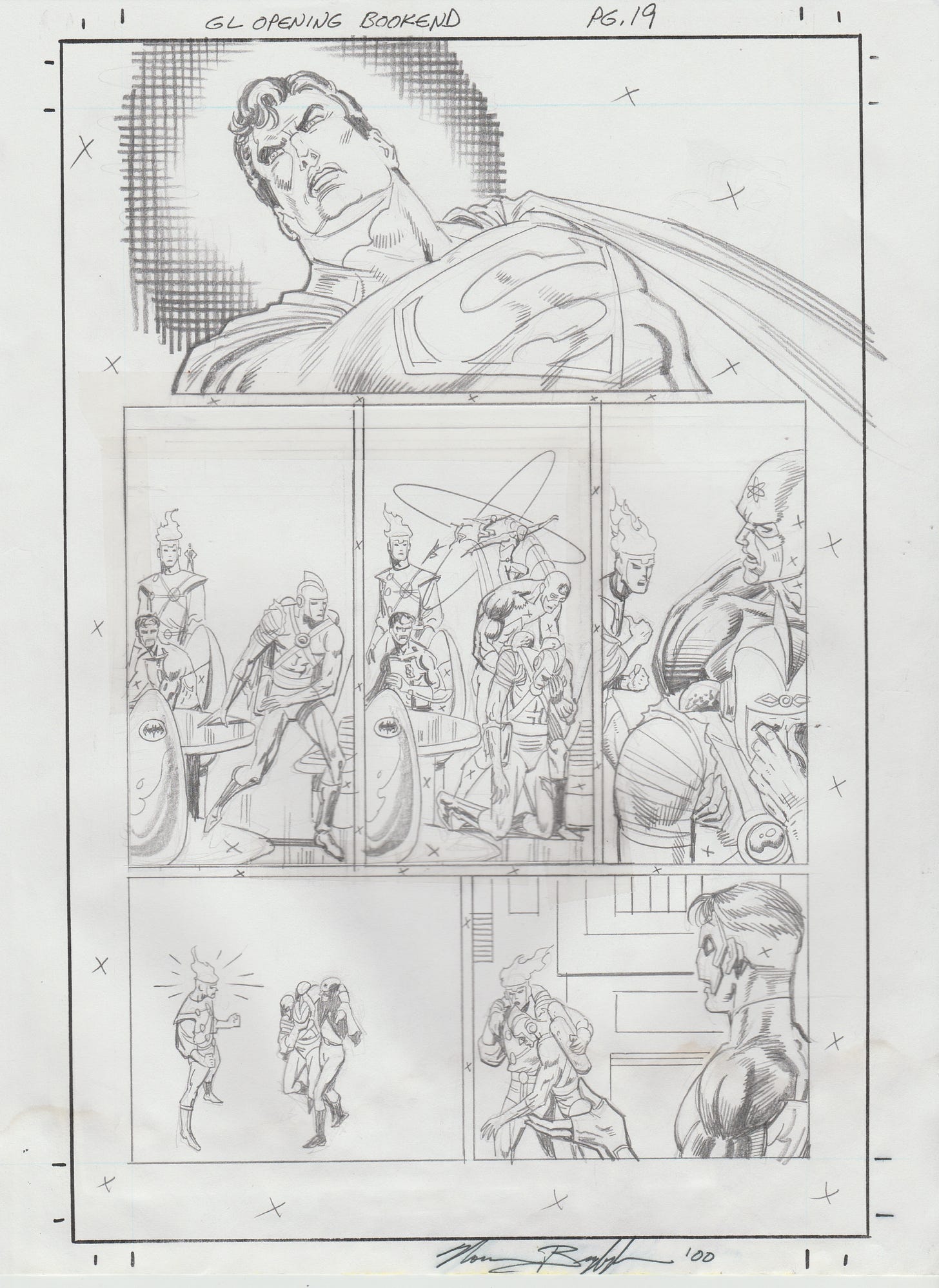

This was how I penciled the Green Lantern: Circle of Fire book, by the way. The inkers that worked on those GL pencils of mine inked them each in their own way. I never talked to any of them about it, but it looks like some or most of them inked the pencils at the actual size I drew them, which I would not have advised, because what I do when I ink my own pencils is I blow up my thumbnails or my 8 x 10 pencils to full size and then I ink them on a light box.

Few inkers have seemed to work that way, at least in the past. For instance, Steve Mitchell didn’t like the idea of working on overlays (on that Detective #627 job where my pencils were lost), he was complaining about the surface of the vellum that he used. Now, I don’t know if he even considered using a light box on that job instead of vellum; you might want to ask him this because I’m curious, too. Inking on a light box is different than using vellum. On a light box you can use actual Bristol board because the light shines right through it and the inker wouldn’t have to worry about it buckling (as vellum does); it would be the exact same surface that an inker is used to. However, using a lightbox you don’t see the pencils quite crystal clear. They’re definitely clear enough for me to ink on a light box and I’ve gotten used to it but it was an adjustment period when I first tried doing that. I didn’t really like it at first. But in fact, that’s how I ink almost everything nowadays, almost all my own pencils, because it’s faster and also because it’s neater: the end results are much neater because there’s no pencil smudges on the final inked pages.

I’ve gotten used to working that way and I can’t say that I prefer it to actually working on the penciled pages directly, but then, I suppose it would depend on the penciller I was inking. For instance, I recently inked three Ron Frenz pages for First Salvo without using a lightbox, and I enjoyed it, but it was an adjustment period back to a different way of working. The main plus with inking on a lightbox is that the ink goes so smoothly on the paper because there are no pencil smudges or skin oils on the untouched surface. Also, different pencillers use different amounts of pressure, and they use different types of pencils too. Any inker will tell you that they have to adjust their inking style dependent on the pencils and that’s something you don’t have to do when you ink on a light box.

Daniel: You wouldn’t ink anyone’s physical pencils anymore; would it all be light box?

Norm: Oh no, that’s not true.

Daniel: Not true? Because I know there are some inkers that just sit there now and go, ‘No, we preserve the pencils, we don’t ink on them’. They will ink either light box or Vellum overlay.

Norm: Oh really? Are there some inkers that prefer inking the way that I ink?

Daniel: Yes.

Norm: That’s interesting.

Daniel: So you’re not alone on that one.

Norm: I’m not in contact with other professionals on a regular basis, so I didn’t know that.

Daniel: So your preference would be to do it on the light box?

Norm: No. My preference is to use a light box on my own pencils because it saves time. When I’m inking my own pencils there’s no reason to do completely detailed pencils. It’s a lot faster if I do them smaller, blow them up on a copy machine, tape them to the back of the Bristol board, and ink them on a light box. It’s just a matter of saving time; and there is the added plus that it’s a cleaner end result, like I said.

But if I had to say what my preference was in general, I guess it would still be inking the actual pencils. But I don’t really know, because I haven’t inked a very wide variety of others’ pencils. So I suppose it would depend on the penciller. An interesting little titbit: I don’t know who it was, but with somebody’s job that I inked about ten years ago, the penciled pages came to me smelling heavily of smoke (obviously, whoever drew it was a heavy smoker). But pencillers will put either more or less body oil on the page, for instance, and that also effects how well the ink adheres to the paper, which is probably one of the reasons you’ve heard inkers say they prefer inking on a light box.

Daniel: I look at Ross Andru pencils that I’ve got and they’re so deep that they’re almost going through the page.

Norm: Wow.

Daniel: Someone once told me that it almost seemed that you could pour a bit of ink in the top corner of an Andru page and it would just flow over the pencil lines, and Paul Neary told me the same about Alan Davis’s pencils.

Norm: Like the intaglio printing process! [Laughter]

Daniel: When you see the original art to the Ross Andru Spiderman sketch that I had you ink you’d see that the pencils marks are so deep, that you can see the indent through the other side.

Norm: Right. I haven’t inked enough of a range of different pencillers for me to really make an objective statement on whether or not I would prefer inking most of them on a light box. My suspicion is that if I were to try out everybody’s pencils, I’d also agree that I prefer inking most on a light box.

Daniel: What pencillers are out there that you actually would want to work on?

Norm: I love inking any others’ pencils, partly because it’s easier than inking my own pencils, and frankly, when a penciller pencils for another inker the penciller’s going to tend to give more complete pencils. When I ink my own pencils I generally have to add some details in the inks. There’s a grey area on how to interpret my pencils when I’m inking on a light box, because I don’t do complete pencils when I ink myself.

Daniel: You’re not overly fond of some inkers. Now what inkers were you fond of? Who do you think did a good job?

Norm: The best inking that I’ve seen so far on my own pencils would be from Kevin Nowlan. I’ve always liked his work. I think he added a certain illustrative quality to my pencils, and our styles blended really well. Nowlan’s a very accomplished penciller in his own right, with a very unique style.

Daniel: And preferred inker of Alan Weiss as well.

Norm: Really? That’s interesting.

Daniel: Weiss likes him and he likes to work with him. He keeps mentioning how he wants to get Kevin Nowlan to do things; in fact they did collaborate on the Young Tom Strong stories.

Norm: Kevin inked Young Tom Strong?

Daniel: He did, he inked at least two stories over Alan’s pencils.

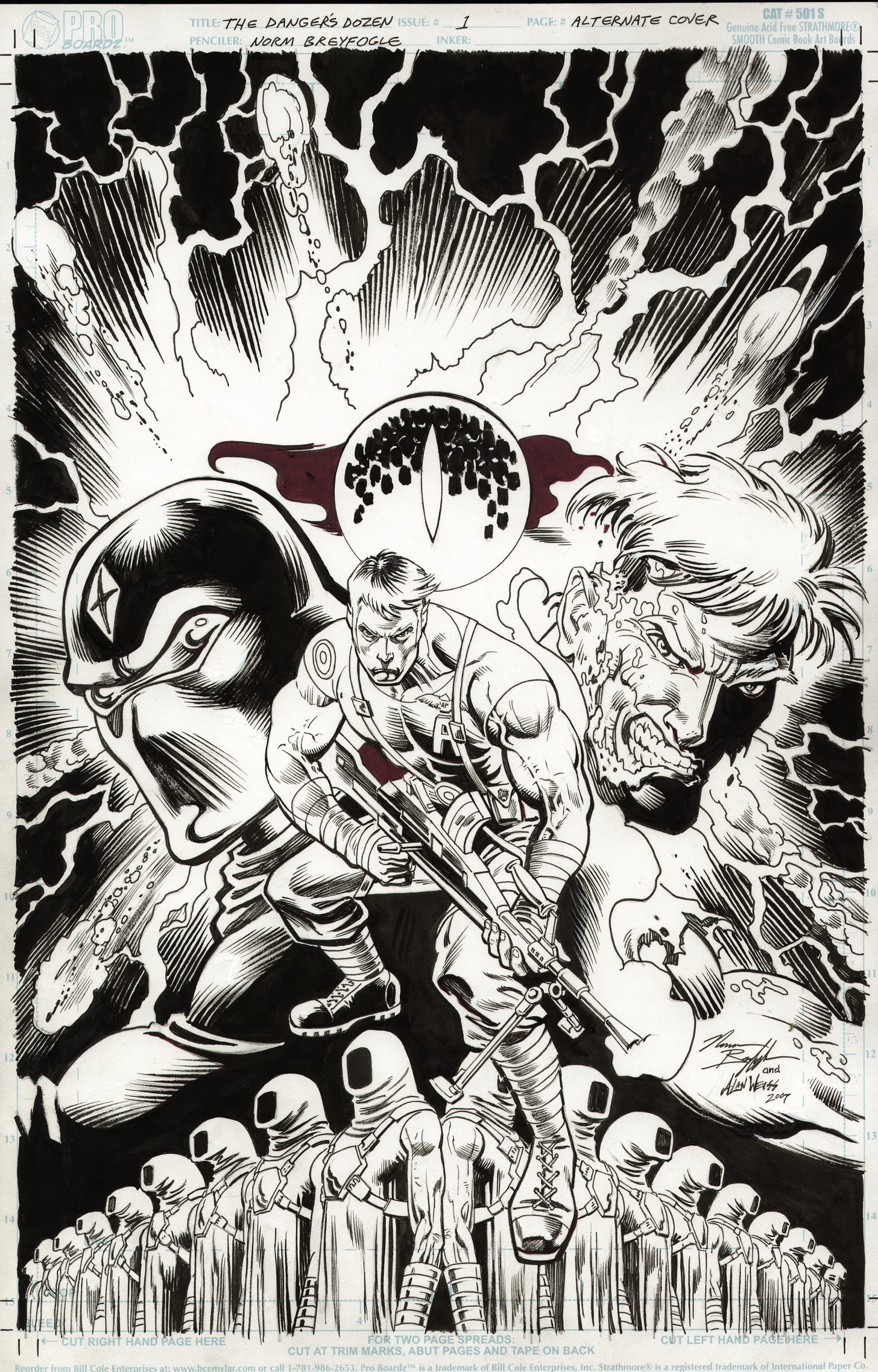

Norm: I’m inking a Danger’s Dozen pinup penciled by Weiss right now. And that’s fun. It’s the first time I’ve ever seen Weiss’ actual pencils. They’re very detailed, very naturalistic. I’ve always considered that Weiss and I come from a similar school, kind of a realistic illustrative school, kind of a Neal Adams school, and yet when I put his pencils next to an alternate Danger’s Dozen #1 cover that I just penciled for him to ink - we’re like swapping like jobs here; he’s going to be inking my pencils, too - when I put my pencils next to his pencils there are big differences, really big differences. It’s amazing.

Mainly my stuff is more influenced by exaggeration than Weiss. Weiss is very naturalistic. I’ve got a naturalistic flare, too, but he’s much more rigorously naturalistic and I tend to exaggerate and be a bit more expressionistic, which anybody that’s a fan of my Batman work wouldn’t be surprised by at all.

It’s funny, people talk about my expressionism on Batman but from my point of view back then and even looking back on it now, the main reason I gained a kind of an expressionistic style was because it was the first long period of deadlines that I was applying myself to. There was Whisper (from First Comics) but that was only for a year or two and I was still warming up. When I finally got the Detective and Batman gigs I was hitting my stride as a professional and the expressionism was largely the result of meeting the deadlines under pressure.

Daniel: You can see a definite growth through the Batman series and I think that’s why people look at the expressionistic style of it. When it starts it’s almost straight art, if that makes sense, but as it went on it just went into a completely different area, certainly with Detective, and then when you went onto Batman.

Norm: Are you saying that my artwork changed a lot from Detective to Batman?

Daniel: Not from the end of the Detective run to the beginning of the Batman run. It just that it kept evolving all along. Certainly from the beginning of the Detective run to the last Detective series you did; you can see a definite change. You can see the progression of growth and the expressionism coming out along with the Will Eisner influences that we’ve pointed out. It’s almost like you were pulling everything in from everywhere and distilling it through yourself.

Norm: I was meeting deadlines so I was always striving for the maximum amount of impact in the quickest amount of time; and this makes me wonder about somebody like Alan Weiss. His style’s remained relatively unchanged from way back in the 1970’s. It’s just as good as it ever was, but I’m wondering what kind of deadline pressures he’s really faced in the past on a long term basis, because for me personally, those pressures really changed the quality of my work, and in my case, for the better, in some ways, in my opinion. I guess it’s just a question of following one’s own sensibilities.

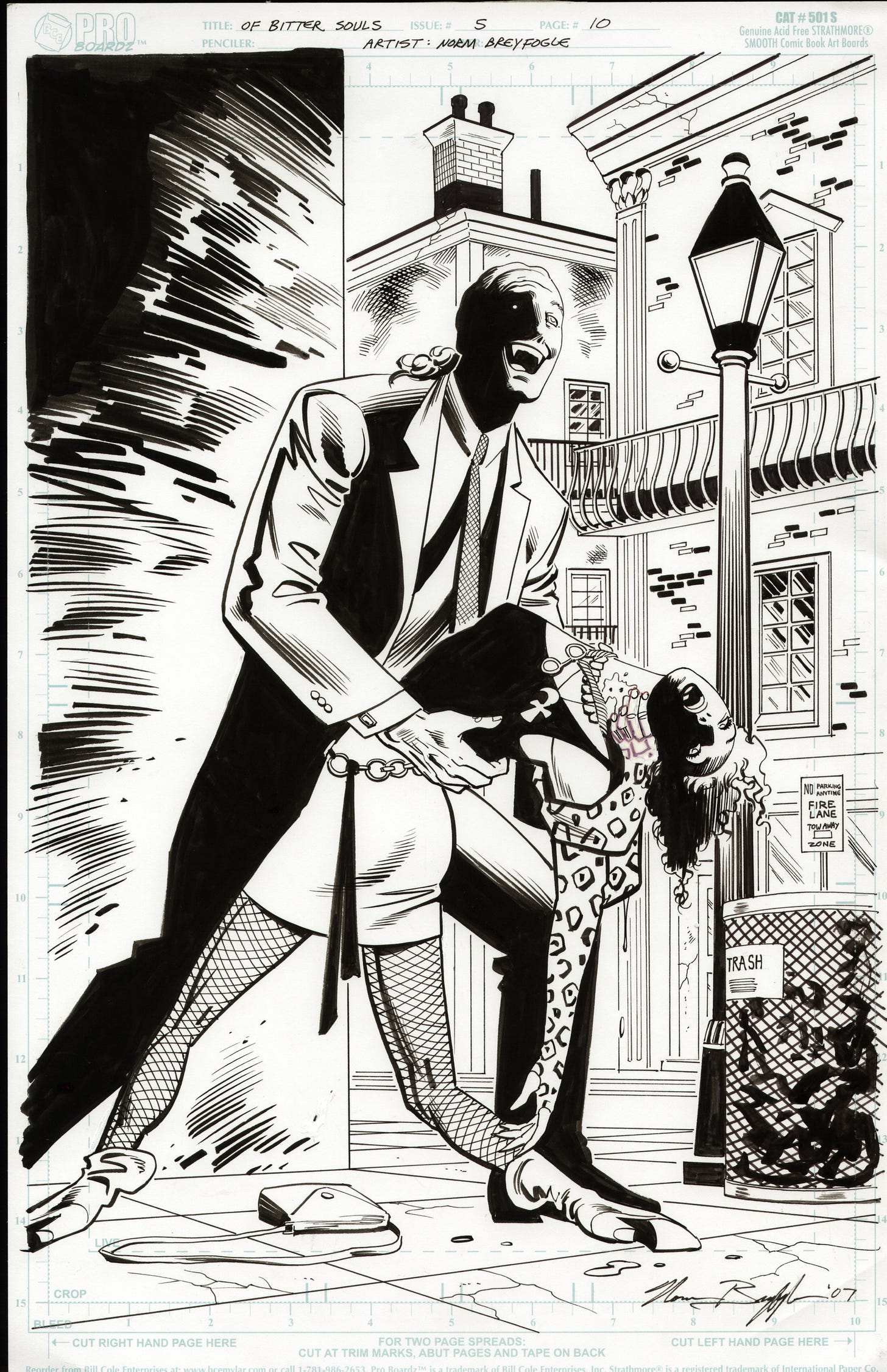

Daniel: We’ve gone completely off track, not that that’s a bad thing. Of Bitter Souls. How did you hook up with Chuck Satterlee?

Norm: Let’s see, it was 1995 or 1994 when I was working on Metaphysique. Chuck was self-publishing Agony Acres and he’d been a fan of mine for a while. He contacted me to do an interview for another publication. After the interview he mentioned Agony Acres and he sent me some copies. I talked to him about Metaphysique and there was a certain similarity between what we were was doing, there was the virtual reality scenario which was somewhat common between them.

So Chuck suggested that I do a pinup for Agony Acres and I did. It was a drawing of the Metaphysique characters meeting the main character in Agony Acres in virtual reality, which was kind of neat. I have a copy of that pin-up somewhere.

But Chuck always wanted to work with me but he never had the funds. In 2005 he came across the funding that would allow him to do his own projects for a while and pay me as well.

Daniel: It was a good series and it didn’t get as much exposure as it should have because of the problems that were going on with the publishers at the time.

Norm: That’s what it’s like for independent publishers in general. My present collaborators at First Salvo seem to be a bit outside of that whole loop because they’ve got their own financial resources. I definitely get a different feeling from them than I do from most American independent publishers.

Daniel: They seem to be more, I suppose, feet on the ground, head screwed on type.

Norm: Well that’s probably it, too. It’s a complex equation but all I can say is I get a different feeling from First Salvo, outside of maybe Dark Horse which is pretty established now.

Typically or traditionally the term ‘independent publisher’ in comics just means anybody outside of Marvel and DC; and Marvel is or has been an independent publisher, too, when you compare them to Warner Bros, who owns DC. DC is the only one that’s not really ‘independent;’ they’re owned by a much larger company. For that matter I might be wrong about Marvel now. Maybe Marvel has changed its financial backing situation.

Daniel: I don’t even think Marvel knows who owns Marvel now.[i]

Norm: I’ve worked for Marvel since that whole confusing stock selling situation of ten years ago, on the Hellcat mini-series. But that was it for me; it was only a few issues and then they weren’t interested in anything more from me.

Daniel: You and Steve Englehart always wanted to work together; how did you hook up in the first place?

Norm: Don’t really recall. After Hellcat we tried to interest Marvel in other ideas and they said, ‘No.’ Steve and I came up with a number of different ideas, I did some drawings for them and showed them to not just Marvel but DC, Dark Horse, a number of publishers in the industry, and none of them were buying so that was that.

Daniel: It seems that you’ve been associated with writers that end up having problems with companies.

Norm: With writers?

Daniel: Yeah. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

Norm: That might just be reflective of a statistical inevitability because most comic creators, writers and artists, end up being dumped by these comic companies, once the creators have had enough exposure. That’s the typical rule throughout the working world, too. They dangle this carrot in front of all the millions of poor people saying, ‘You can get rich too, just follow the system that we’ve set up for you,’ and yet the whole system excludes them almost totally and only a tiny fraction of people ever get through. It’s a giant scam.

Daniel: Yes but we all live in it.

Norm: Yeah, well, I’m not saying that there’s anything better! [Laughter] I’m just saying that it’s a scam. I was allowed to believe that if I applied myself I could work for these companies for life, and yet it isn’t true.

When I was dumped by DC and Marvel and I had no work to do, I started writing because I didn’t want to draw anymore, I was burnt out. I had drawn all my life. First, all my amateur years, all my years growing up, I’d drawn and painted for no money at all, just for the sheer joy of it. And then I started making a living at it, and after 15 years of doing that on a regular basis and meeting the deadlines and suddenly being cut off, I had to face the fact that I didn’t have any motivation to draw if I wasn’t going to get paid for it! It was terrible. It was like they’d used up my talent. My talent was still there, but they had commandeered it, they’d hijacked it for a buck, exhausted it in a sense. They’d hijacked my own motivation for drawing. So instead of even bothering with that I began writing instead.

When my career was cut off I did in fact try to find comics work, with Steve Englehart, for instance, and there were numerous other examples. There were numerous proposals I made to DC which were all shot down. And that was the main reason that I said, ‘Why should I even bother with this anymore?’ I could have kept drawing but I did feel kind of burnt out with drawing, so I switched to writing instead. God, if I could make a living just at my writing! Of course, there would have to be no deadline pressure and I’d have to be paid as much as I want. [laughter] That would be my ideal life.

Daniel: We all want that.

Norm: Not all of us have the talent or the opportunity to concentrate on it. There are a lot of people out there that don’t really have talent and they think they do.

I had some difficult experiences, looking at some fans’ work when they’re so gung-ho about their stuff and they have this naivety and energy that’s challenging in some way. ‘I challenge you to tell me that there’s something wrong with it and the work is crap.’ So what do I tell them? It’s difficult to face a person like that, who can’t see their own work objectively. And I know I can be like that myself sometimes! Heck, sometimes it’s even difficult to praise some people’s work, due to their attitude. [Laughter]

Daniel: Look, we’re all like that. I find it hard to accept praise. Actually I think almost everything I do is crap anyway, so I find it hard to be objective and accept it.

Norm: Oh, you’re being overly modest. You can tell when you write some good stuff.

Daniel: I like to think I can, but sometimes I can’t. I suppose I don’t know if it’s any good because nobody ever tells me.

Norm: Nobody tells you?

Daniel: It’s a lack of feedback. However I get too embarrassed to ask at times. But then on the other hand it can’t be all crap or people wouldn’t come back to read more.

Norm: That’s true.

Daniel: For you, it would be like you’d drew your Anarky series and no-one ever told you if it was any good.

Norm: Yeah.

Daniel: How do you know if it’s any good? You may think it’s good, but do you know it’s good?

Norm: Well, that implies that there’s some kind of objective standard. Is that what you’re meaning to imply?

Daniel: Well, no.

Norm: You’re not completely dismissing it though.

Daniel: No, not completely dismissing it, that’s not what I’m implying. It’s that reinforcement, the outside reinforcement.

Norm: Right, that’s the point. That’s what you’re getting at, is that reinforcement is important.

Daniel: Yes.

Norm: That’s exactly what happened with me with comic book art. When I suddenly wasn’t getting any bites anymore, I wasn’t getting any more work, the reinforcement was completely gone. It was like the floor just dropped out from under me and I was falling. I had to change, I had to do something different, I couldn’t just keep drawing. That’s how I felt.

But it changed, it changed. Once I got used to the new situation, outside of my debt which has kept me working for companies for page rates, which is fine, I’ve been lucky. I suppose I’m lucky that I got Batman when I did because I probably got a name in the industry which will always find me some work somewhere.

Or at least it has so far, and I’ve been kind of surprised by that, frankly. I was prepared to completely leave comics entirely when I moved up to Michigan. I thought my career was over! I didn’t know what I was going to do. All I knew was I had a bunch of debt and I was facing a life changing situation.

Daniel: The Batman stuff, as you said that will always carry you through, you’re always going to be a Batman artist and being one of the Batman artists means you could go to any convention and they’re always going to put you out there as, ‘Batman artist Norm Breyfogle’. You’ll always have that and it means people are always going to come and ask, ‘Oh can you draw me the Joker, can you draw me Batman, can you draw me Robin, can you draw me Ace the Bat-Hound’. [Laughter]

Norm: Nobody’s asked for that.

Daniel: Well, there’s still time.

Norm: Well, actually probably somebody has, but I just don’t recall it.

Daniel: You drew a good Ace. If you’ve got a pencil, someone could ask for Ace.

Norm: Yeah, I actually feel very grateful. It’s like what Pelé once said, ‘Soccer has been very, very good to me.’ People have made that statement in so many other areas. I feel the same way about Batman and DC Comics. Sure, I’ve got complaints about the bureaucracy and about the transitory nature of fan and editor appreciation. Very few fans stay comic fans all their lives, although that number seems to be growing. I hope it’s growing. But traditionally it’s been considered true that a fan is a comics fan for about three years and then they move on to girls or whatever, and I think there’s still a lot of truth in that.

Although I must say I was watching the show about the San Diego Con and they have all these adult fans in the background walking around while the filming was going on with the interviews and at one point I thought, ‘You know almost everybody there would probably recognize my name’. Which is kind of neat.

Daniel: Absolutely, that’s the rush, that’s the positive reinforcement. Just how bad did things get after you did your last stint at DC?

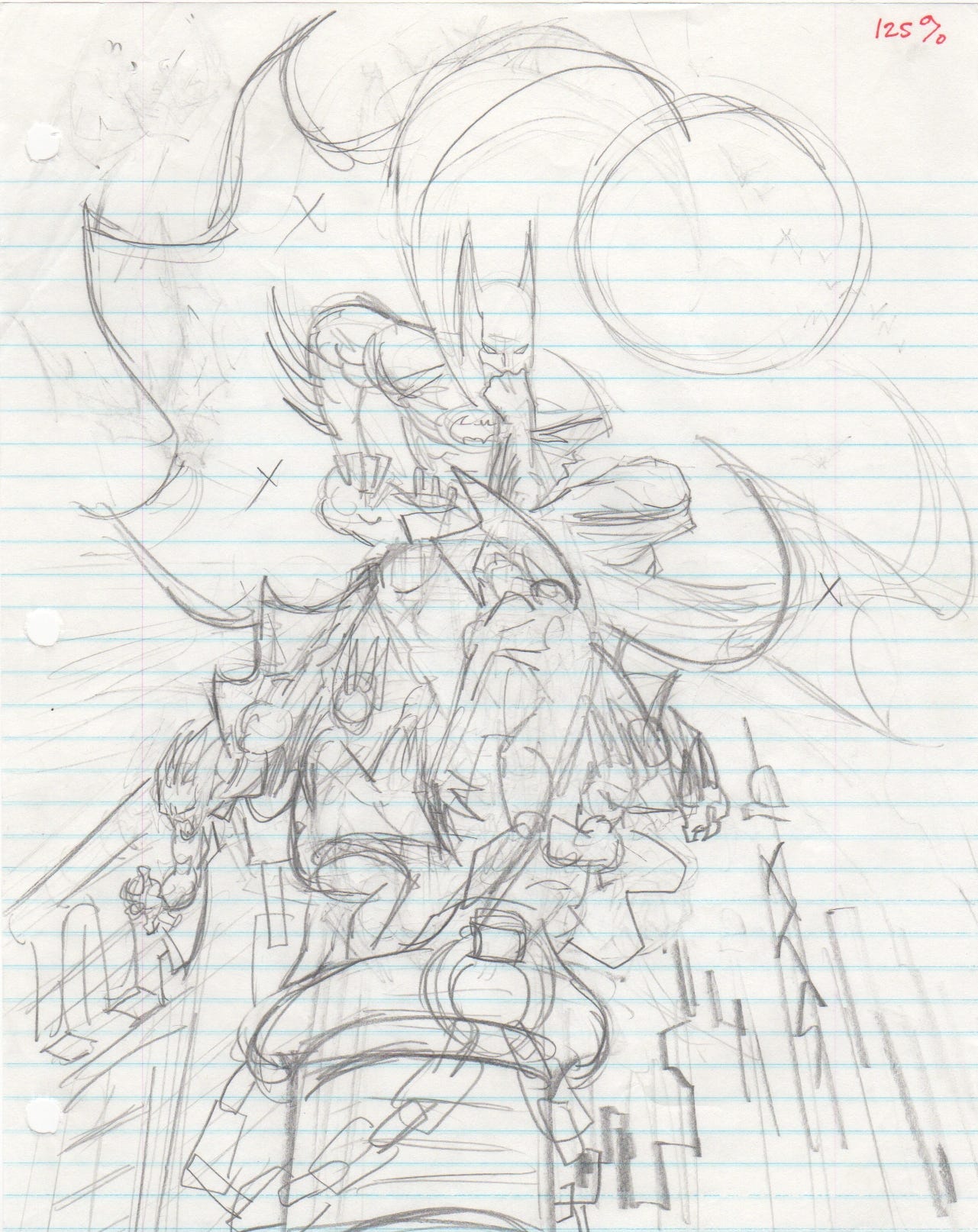

Norm: I thought my comic book career was over, because Marvel and DC suddenly just pulled the rug out from under me and that was it. So I threw all my Batman thumbnails out, along with the photocopies of all the pre-inked penciled pages. Part of me is kind of glad that it happened. It’s an interesting bit of news isn’t it? A dramatic illustration of how I was feeling.

Daniel: I can respect the reasons why you did it.

Norm: There’s something else that I don’t know if I’ve mentioned to you before. When it first happened that I wasn’t getting any more comics work I came up with the idea of holding a fire sale for all my original comics art pages. I was going to put it on the ‘net; I was thinking about different scenarios where I could burn a number of pages a week or maybe one page a day and the only thing that would save them from the fire would be somebody buying the page.

Mike Friedrich, my agent at the time who was going through as big a transition as I was, of all the people that I talked to, thought it was a brilliant idea. He thought it was absolutely great. Obviously he had some frustration about how the publishers were treating older, experienced talent. So I was actually getting gung-ho about my fire sale idea. I called the organizers of the San Diego Con back in 2000 or 1999 or so and I brought this idea up to them. I would have a panel discussion at the con where I was would unveil my idea. And they hated it! They said it was too negative.

Daniel: It’s funny but it’s…

Norm: It’s funny but they didn’t think so, they thought it was negative. They were horrified! It was like I said, ‘I want to rape your daughter on film,’ or something.

Daniel: It is shocking. I’d sit there thinking, ‘You’re going to do what?’

Norm: Well that was the whole point. Somebody had pulled the rug out from under me. I felt like I had been capped, knee capped, like Nancy Kerrigan, so that I couldn’t skate.

And I felt like, well, they’ve painted me into a corner, I’m impotent. So what can I do? And the only thing I had of value were all those Batman pages and all the other pages that I’d published. I thought, ‘Hell, this is a lot of historical value here. I could hold this stuff hostage!’ I actually considered doing it, very seriously. In fact, I wouldn’t even write off the possibility that I might still do it someday.

Daniel: Oh God, just don’t you dare. No, that’s not fair.

Norm: Well, this world is insane.

I’ve got to admit, though, that enough time has passed, that difficult part of my life has largely blown over, and I’ve been selling my pages, and I’m now really glad that I didn’t burn those pages. But life is short and it was a good idea. Nobody’s done it before or since. I still like the idea. After all, it expresses something beyond mere desperation. It expresses something about the fundamental value of money or even about history. It’s an existential message. It forces those who hear about the Fire Sale to confront basic existential issues such as: what is the value of art? What is the value of physical reality? How important is a person’s public persona? Can we exist without it? Am I strong enough to be a human being without all this stuff? These are not living beings; this stuff is just ink on paper.

Daniel: At the end of the day, they’re your pages you can do what you like with them.

Norm: Well, that’s true.

Daniel: You can put them on the floor and soak up water, like Marvel used to do with Kirby art back in the ‘50s. It’s your artwork.

Norm: It’s the only thing I had left, when I thought my career was over. All I had left was original art and it suddenly dawned on me that this stuff’s worth a lot of money. So I could do something with it. I could make a social statement; I could get attention. I could even get money out of it. But in any case it’s a powerful commodity to some degree, it’s got a certain amount of value, and so I wasn’t completely impotent and that’s what I liked about the Fire Sale idea. I was feeling so fucking impotent at that time that it rejuvenated me, and obviously Mike Friedrich felt the same way. I was very surprised at how enthusiastic he was.

People have asked me if it bothers me when I see my sketches, commissions, or pages that I’ve previously sold now selling for more than I got for them. My painted covers going for thousands of dollars when I’d sold them for mere hundreds. It would bother me more if art was going for a dime. I was stupid and I did sell a lot of that stuff myself way too cheaply, but I did sell it for what I considered to be a decent amount of money and I was willing to let it go. I didn’t sell it out of desperation because somebody offered me something that I thought was way below its value. It was my free, stupid decision. So it doesn’t really bother me.

But it’s amazing. I’ve often said that when I sell a piece of original art to somebody they can do whatever they want with it I’ve even said at times they can use it for toilet paper if they want because they bought it and they now own it. I have copies of the art, scans of it, so, fine. Right? But when this recent thing came up with the DC trading cards, where somebody was selling the originals that they’d colored themselves and their painted colors are mixing with the non-waterproof ink I’d used, well, that changed my opinion!

Daniel: Why did it change your mind?

Norm: What it comes down to is I don’t mind if a person resells the art for whatever money they can get it for or who they sell it to, but when it comes right down to it though it is insulting to have the artwork destroyed. That’s all. Just please respect the physical integrity of the art.

But it’s not that big a deal to me because I was willing to have a Fire Sale and potentially burn everything, so how insulted can I be? [Laughter]

Daniel: Well you can be highly insulted.

Norm: I can be but it wouldn’t be very consistent.

Daniel: No, it’s your art. If you want to destroy it, that’s your choice. However if I buy it, deface it and try and flog it off to someone without informing them of what I’ve done, well that’s misleading. My main complaint about those two trading cards wasn’t what they’d done to the original art; it was more that they were selling it as an original painting by you when clearly it wasn’t. It was false advertising.

Norm: Well, they misrepresented it. That’s got to be illegal.

Daniel: You can burn your stuff, you can use it to line the kitty litter tray, you can do what you like with it, and at the end of the day the art is yours. But if I do it, well I might as well slap you in the face and say, ‘This is what I think of you as an artist’.

Norm: Well that brings up some interesting side experiments that I’ve never really thought about.

Let’s say somebody, for instance you, were to buy all of my original art and you can even tell me up front, ‘Okay I’m going to give you this price for it,’ and I agree on the price and maybe it’s a good price, could even be a great price, but the stipulation is that you’re just going to burn it all? Actually burning it all wouldn’t be as bad as defacing it. Because if it’s defaced it still exists but in a lousy form, and people might get a bad opinion about the original. Obviously there’ll still be a scan of it somewhere.

Daniel: Well the original will always appear in a book. I could buy all of your Anarky stuff and go right, ‘Now I’m going to let the three year olds around the corner with their crayons color it all in’, but at the end of the day anyone could pick up one of those Anarky books and read it and there it is in its, not in its purest form, but it’s there.

Norm: It’s funny. After working for 20 years in this industry I haven’t really thought these things through thoroughly. I guess I was on such a treadmill and the system is already set up and the laws are there and general rules of behavior are there that have never really been challenged until recently (like, for instance, with those trading cards).

But when I think about it, I realize that I haven’t really thought about it much at all.

When you get right down to it, all of my comics work isn’t as intrinsically valuable to me in the greater sense as are some of my favorite poems or short stories. If it’s sold, if it changes hands, it still exists. What’s the difference? It’s not in my possession anymore. It’s when it comes to defacing the work permanently that it’s a whole new territory for me.

Daniel: Did you read what I wrote this morning about the Ross Andru pages that someone used for target practice because he couldn’t sell them?

Norm: Someone used them for target practice?

Daniel: When I was writing the Andru and Esposito book I started looking for pages from Zen the Intergalactic Ninja. I was told that there were none left. I asked why that was and an art dealer contacted me and said, ‘The reason there are none left is because I bought them all. Bought them for $5.00 each or something, couldn’t sell them. Someone offered me $1.00 each for them, so I took them out and used them for target practice and then sold what was left’. I thought ‘You stupid tit’. He shot up about 30 pages. To me that’s just wrong.

Norm: It should be illegal! If you ask me, it should be illegal to destroy art. There’s a grey area, obviously and it brings up an endless amount of questions. If I want to destroy my car, if I want to burn my car I can’t. I haven’t looked into it but people have told me that that would be illegal. Even though I own the car! I don’t owe anything on it. I own my car lock, stock and barrel, but apparently it’s illegal for me to burn it, although I might be able to find some special circumstances in which I could burn it. But obviously there are a lot of grey areas here that most people don’t even think about at all.

Speaking about some of the treatment of original art of the past brings something else to mind: the loss of all the pulp magazine cover paintings from the 1940’s, before comic books got big. Out of all those painted covers, there’s only like a very tiny percentage, less than 10% of those paintings that are even in existence. Most of them have been destroyed or lost and it’s astonishing when you think about that. And at the same time so much stuff is being produced all the time that it begins to seem almost inconsequential. How valuable is this stuff?

Daniel: It’s like anything. It’s worth what everyone’s prepared to pay for it.

Norm: Right, right. But in the long term sense, in the cosmic sense of time, our entire culture is nothing but a grain of sand.

Daniel: It works for me.

Norm: Given our own culture with its capitalistic value of the bottom line, its reduction of everything to an economic commodity, and given human nature, the transistorizes of the length of a human life, and the rarity of the finer appreciation of things in life, most of the valuable things are just going to be lost to time. Eventually everything is going to be lost to time, of course.

Daniel: Now one of the things we haven’t spoken about is the Valiant stuff that you did.

Norm: I didn’t do much for them at all. It was right during the implosion of the comics industry. Valiant was apparently experiencing the pressures of lower sales and so they had this publicity stunt called Break Through, or actually maybe that was the name of an Ultraverse stunt. Valiant had something like that though; I forget what they called it.

Anyway, basically they hired a number of higher profile artists and writers from outside of the Valiant stable to contribute to their books. They actually flew many of us out to New York and there was a press conference and I wore a suit with this Swiss cheese tie. Actually, it just looked like Swiss cheese; it was made out of rubber. It looked like a polka-dotted tie from a distance, but up close folks commented on it. ‘Oh that’s great; I like your Swiss cheese tie.’ That was the first place I met Neal Adams too, because he was contributing to the Valiant stuff, as well. He was doing that female vampire; I forget the title. He was writing and illustrating it. Beautiful work. I met Neal Adams and shook his hand and then he just started talking. That was it, man. Once he starts talking, you can’t get a word in edgewise unless you’re really on the ball and I frankly didn’t feel like I was.

Daniel: He’s got a lot to say.

Norm: He seems to have a lot of motivation to say it, too.

I felt a little strange because he was an idol of mine and sometimes I wish that I’d accepted an invitation back in - when was it? - 1989 or so, to join Continuity.

I talked to Alan Weiss and a little bit to Alan Kupperberg, and they told me stories about Continuity. They had negative and positive stories, but it was definitely a formative experience for them, and I can’t help but think that I missed out on that. And I did have that opportunity but I turned it down.

Daniel: We’ve spoken about this before. How would you have thought if you’d become a Neal Adams clone?

Norm: I’m sure that would’ve happened, actually. I don’t have that temperament. In fact it’s a good question: what would have happened? I’d have to speculate, but more than likely I would’ve ended up getting into arguments with Neal Adams and I would’ve had to leave. They would’ve been very abstract arguments but I suspect it would have been just too much and I would’ve had to leave.

Adams is definitely a lightning rod of interest, that’s for sure, and he was and is very talented. And he’s very extroverted, while I’m not. Not as much, anyway. I’d like to know a lot of things about him that I don’t know. I’d like to know what his astrological sign is. I’d like to know what his home life was or is like. Does he have brothers or sisters, I don’t even know that. Do you know that?

Daniel: I don’t know if he’s got brothers and sisters. I know he’s got kids.

Norm: Right. I know he’s got children too; they’re about my age. In fact, I’d be just the right age to be one of his kids, and in a sense I am. A lot of us in the comic book community are Neal’s artistic kids. Even though I didn’t belong to Continuity, Adams was a comic book god to me for quite a while.

Adams was by far the best comic book artist that I was fully aware of in the 1970’s. He stood out heads and shoulders above everybody. Of course, I wasn’t very aware of a lot of other stuff. I wasn’t really aware of what was being done in European comics, well some of it I was. Or like in the large sized Creepy and Eerie and Monsters Unleashed, the oversized black and whites, they had a large variety of illustrative styles that I sometimes saw. That stuff blew me away, but I didn’t see a whole hell of a lot of it. Mainly it was the Marvel and DC stuff I gravitated to, and Adams stood out so far above almost everybody else in that milieu, at least for some of us.

Daniel: But certainly lot of people my age would say the same thing about artists like Paul Gulacy, Michael Golden, John Byrne, Walter Simonson and Frank Miller. I know I started with those guys and then worked my way backwards. In Australia we used to have these little digest size Marvel reprints of three or four comics and they were about 50 cents or 60 cents each and I’d buy them. I’d sit there and read them and it would be Jack Kirby or Gene Colan and I’d think, ‘This is good, I like this’ and I’d work my way back from there. Whereas a lot of people worked their way forward, it was only by going backwards that I actually found an appreciation for that stuff. I always thought Jack Kirby’s stuff wasn’t as good as Gulacy or Byrne’s, that’s how I saw it at the time, albeit through younger eyes.

Norm: I always said that, too, as younger person.

At my very first San Diego Con, I attended a seminar taught by Sal Amendola, along with a small number of relatively new artists who’d contributed to New Talent Showcase, the DC Comics title Sal was editing. Anyway, I went to a McDonald’s for lunch with one of the up-and-coming artists and I told him that I didn’t like Jack Kirby’s stuff, that I couldn’t understand why anyone liked it because it looked so cartoony, it didn’t have any realism to it. Well, it was like I’d said the Pope raped babies or something! It was tantamount to a religious affront to him, and so I started thinking about it thereafter, I looked at it more closely, and I pretty quickly changed my mind about Kirby’s value.

I’d only pursue what attracted me, and I didn’t really look into the stuff that didn’t. When I finally researched Kirby and discovered what he brought to comics, I realized why he’s called the King of Comics. He brought dynamism to comics that didn’t exist before. He was the first one in mainstream American comics to really play with panel designs, bringing in the single page spread or double page spread, making that of essential dynamic interest; and he brought in lots of special effects and over-the-top machinery and a lot of amazing characters.

But I still don’t like the thing that didn’t attract me from the beginning, which was Kirby’s lack of illustrative naturalism.

Daniel: John Romita once told me that Kirby was the best there was. He said, ‘Look this guy had imagination that none of us ever had. But he created a living planet as a villain; do you know who else could do that?’ I agree with that but I felt that Kirby’s failing was his actual dialogue.

Norm: That’s why he and Stan Lee made a good combination. Stan brought in a more hip and modern feel to the dialogue. Kirby was great at the big picture and idealization of storytelling, but when it came to the dialogue, from what I understand, he wasn’t really that great. But of course looking back on it, from today’s perspective, Stan Lee’s stuff wasn’t that good either. But it was a big change; you’ve got to take it all in context.

I didn’t see Kirby’s strengths because I was so focused on developing my modernistic, naturalistic, illustrative skills. I didn’t see the big picture. I wasn’t aware of the fact that when he was breaking down these plots from Stan Lee, Kirby was largely telling the story, and he was inspiring Stan and bringing a lot to it that Stan didn’t specify in his plots. I wasn’t aware of any of that; and when I did become aware of it I changed my opinion about Kirby. In the final analysis, Kirby was the King of Comics because he was a consummate storyteller in terms of the heart of comics, which Scott McCloud innocuously calls ‘structure’ in his book Understanding Comics. I think it’s like his step three in the production of comics, the middle step. He doesn’t call it the heart of comics as I do, but just like the heart chakra in the esoteric energy system of the Far East which you can call the fourth chakra, it’s also so much more than that; it’s at the center of the ladder from the concrete to the abstract, so it’s therefore the heart, it’s the middle of the whole system and it holds the whole thing together.

In the same way, McCloud’s step three ‘structure’ is more than that; it’s the very heart of comics. McCloud calls it structure because he’s a very rational guy and almost scientific in his analysis of the comics form.

Structure sounds innocuous but that’s the thumbnail stage, when the artist translates the script into visuals for the very first time, and that is literally the heart of comics, the bridge between the abstract and the concrete. I don’t know if Scott has ever called it that, but that’s what I call it all the time; and that was one of Jack Kirby’s greatest strengths.

Daniel: Just talking about Batman, for example, in the late ‘70s you had the likes of Jim Aparo ,Michael Golden, Don Newton, Gene Colon, David Mazzuchelli, Trevor Von Eeden, Starlin and Simonson. Each of them had their strengths and merits, and all are stunningly good artists, however out of all of them I always liked Aparo’s clean line.

Norm: You can’t find a better storyteller than Aparo. Even Kirby wasn’t a better storyteller than Jim. It’s awesome how well his best storytelling flowed visually speaking. Even his later stuff where the illustrative qualities, the actual rendering and anatomy and all the details of the illustrator’s craft started to look hacked out, the storytelling remained because he had internalized it so completely. And good storytelling, like anything rare, is going to be rarely appreciated unless it’s focused on by those sensitive to it.

If we were to lose our modern culture, if we were to lose our technology, diamonds wouldn’t be considered culture, wouldn’t be considered valuable anymore because they wouldn’t be viewed as rare because you can’t do much with a diamond. The best you can do with a diamond is make a better axe or a spear to kill your enemies. It’s only with a certain amount of sophistication - and this is only a metaphor of course - it’s only with a certain amount of sophistication that we realize how rare, how valuable a diamond is because of its latticework of carbon atoms.

It’s the same with anything else. Statistically speaking, the most rare and valuable things are going to be appreciated only by the few unless the rarity is hyped, unless it’s advertised, unless it’s pushed by people in power. People that control the flow of information.

Now, you’ve often said - and I’ve really appreciated this - that quality will win out in the long run. And I think that’s somewhat true. I think it’s largely true. In fact in the longest run it’s probably ultimately true. And so, in the long run we appreciate Kirby’s storytelling abilities; in the long run we appreciate Aparo’s fluid storytelling; in the long run, hopefully, folks will appreciate Breyfogle’s storytelling abilities.

Daniel: Your work hasn’t deteriorated over the years, whereas you can look at other artists and as they became disinterested with a book or disillusioned you could see it reflected in their work. But you’ve not succumbed to that jadedness and that problem that a lot of artists do and a lot of writers do as well, when the book’s been taken from you.

Norm: Well, I’m desperate. [Laughter] What I mean by that is that this is something that I’ve devoted my life to. I ‘desperately’ want to produce quality.

Daniel: I don’t know whether you will admit to it or not, whether unconsciously or consciously you’re aware of the fact that everyone will remember the last thing you did. People look at your last Batman and go, ‘Oh that was good’.

Norm: I’m really not aware of that. That’s interesting, because to me that’s not how I look at things. If I don’t have any knowledge at all of a creator and all I see is the last thing they did and it’s crap, yeah I’ll get a bad impression. But generally speaking, I would never assume that the last work that somebody did is representative of their total output.

But that brings up something else, and it’s something that I became aware of very early in my comics career when I first started seeing my stuff in print: I felt I could see it more objectively then. I suppose it’s true for a writer to a certain degree, too. I know that for me, when I type something up I can be much more objective about it than I can when it’s handwritten. It’s the same thing with art, for me. When I see my art in print I can see it objectively much better than I can during my drawing process. Well, what that did for me early on when I was drawing Batman and Detective, was that it put me in my place. It made me realize that, okay, inside of me I may have this consummate storyteller, this dynamic artist that I’d love to get out, but after the production process when I saw my stuff in print it looked kind of crappy in comparison to how I’d thought of it. What it brought home to me was how important, how permanent print is. It’s not really very permanent, of course, but in terms of my lifetime it’s pretty permanent, and that’s all that I’m really concerned about, because once I die I’ll probably be in some other solar system or in another universe or whatever. [Laughter]

But I became very aware, very early, that the stuff that gets into print is going to be there when I’m 90 years old if I make it that long, and that’s going to haunt me either for good or ill, so it became very important to me to produce quality work as often as possible, no matter the purpose of the work.

I’m reminded of the Pulp and Golden Age comics artists and how so much pressure was put on them to work quickly but in fact they often produced brilliant paintings regardless. And almost all of them believed that their stuff was worthless! It’s utterly amazing. Even the best among them thought their work was worthless because the culture told them that it was worthless and paid them very little. And yet something in them, some dedication to quality made the best of them produce good work.

Daniel: Are you capable of producing a bad job?

Norm: Of course, everybody is. I’m not sure what the spirit of that question is. What do you mean exactly?

Daniel: Are you physically, consciously capable of producing a bad job?

Norm: You mean would I ever choose to do a bad job? For what reason?

Daniel: Well, for whatever reason.

Norm: I can’t imagine a reason. Can you imagine a reason?

Daniel: Let’s say a book’s been cancelled or you’ve been promised a certain amount of money or creative freedom and you find out that you’ve been lied to.

Norm: No, that doesn’t affect me. You’ve mentioned that before and I don’t get that at all.

If I’m going to see something in print I know it’s going to haunt me for the rest of my life and even if few see it, I know that it’s going to exist. The scans will exist, the originals will exist and I want them to be good.

I guess I should be proud of this. I’ve never really thought about it because it’s just so intrinsic to my nature. But obviously I’ve been pressured by deadlines to produce work that wasn’t as good as it could have been. But under the pressures that I was facing, I always strove to produce the best work that I could, and frankly it’s a big sacrifice to do so.

Being an artist, let alone a comic book artist, where the pressures are so great, but even any kind of artist, if you care about your work your artwork becomes your life. It becomes just about the most important thing. In fact, I would say that in my opinion the definition of an artist of any kind, whether it’s musical, visual, you could call an athlete an artist, an actor an artist and so on. The definition of an artist is one who puts the quality of his artistic work ahead of everything else, except maybe his soul. And that’s why it can potentially be compromised for family and marriage, or other life situations. The classic example is Van Gogh. He was completely alone; he was miserable his whole life and now he’s considered the greatest artist of all time. It’s a terrible stereotype and it’s not true across the board at all, of course, but it is one of the archetypal signposts in the life of an artist. Obviously the truth is more a mixture of talent, vision, motivation, and all the other pressures put on one. But to the degree to which a person or an artist dedicates himself to the quality of his work, that’s largely the degree to which he’s going to be a good artist; and obviously if you dedicate yourself to one area, you’re going to have to take some dedication away from another area because there’s only so many hours in the day.

I think it’s true for everybody, not just artists. If you’re a mailman and you really think that doing a good job is important, then the same thing applies there, too. It could apply to a family man, to being a father. If I had a child, that child would be more important to me than my career, no doubt! Obviously there’s a complex interaction of values there because my career and its success is going to affect the child, so it’s not a cut and dried situation, but the child is going to be of utmost importance to me.

Daniel: I think what comes across to me is the dedication of the artist, the dedication of a person to do the best possible job you can do. So why would anyone want to hack something out. Do they not have any dedication or discipline, or are they doing it deliberately just to prove some stupid point? I’ve never understood anyone hacking anything out. Vinnie Colletta I can understand hacking out; he needed the money and he generally got the stuff at the last minute and had a few days at best to ink an entire book. But when you’re dealing with a professional who hacks out and deliver sub-standard artwork saying that it’s his best effort, or even worse, admit later that they didn’t put any thought or care into the work, well I just don’t understand it, I really don’t. I can’t think of why you’d knowingly and deliberately want to put crap out there and put your name to it.

Norm: Obviously if you think you can get a fast buck with less effort that could be motivation for a person. Here’s a good example: when Mike Grell was doing John Sable Freelance, did you ever see any of that?

Daniel: Oh, years ago.

Norm: Well his last few issues were done when it was to be cancelled, he did the last two or three issues in a very rough style where it he looked like he was, well, you know Mike Grell’s style. It’s extremely detailed. It has all these really close parallel lines and shadings and frankly, I’ve never really liked it because it appears he’s too overworked, it’s too mannered, it’s too stylistic, it’s not naturalistic enough for me. Anyway, I was surprised at those final issues of John Sable because they were apparently whipped out, but the results were better! I told Grell that when I met him at a convention. I said, ‘Wow, I loved those last few issues because they were more gestural, you could see the quality of the brush on the page, you weren’t obsessing over all these highly mannered details.’

Now the fans, in reaction to those issues, which I read in the letters column, considered Grell to be just hacking that stuff out and I got the impression when I talked to Mike Grell briefly about it, that he felt the same way. He’d basically been convinced or maybe believed from the beginning that he was hacking it out because he was getting more gestural and he was not putting as much effort into it. But from my point of view it was better work! It expressed more of the gist of his ability to draw.

But you’ve got to understand that traditionally, comic book fans have been quite young, and young people obsess over detailed renderings and the intricate, sparkling jewels of awesomely time-consuming work, and they often miss the big picture. They miss the basic structure, the storytelling which I told you before is the most important thing, and that’s what I was trying to get out before is that such an appreciation is a refined sensibility. Well that’s what came through for me in Grell’s last John Sables stories (from the late ‘80s; I know Sable has been back since then).

I almost feel kind of sorry for Grell because he’s created an expectation in the fans for this highly stylized, highly detailed, time consuming artwork that frankly wasn’t as good as his more gestural stuff. But then again, subjective taste plays a big element in all of this. I’ve always had an appreciation for Joe Kubert and Nick Cardy because you could see the brush strokes. It’s not highly time consuming stuff, but its pure gold.

Alex Toth is probably the penultimate example. Toth could make an economical statement that showed such a deft knowledge of what he’s doing that it was almost like he was doing it with joyless abandon, although of course there’s actually a lot of concentrated skill there.

I think what it comes down to - and this gets down to the core issue of why the comics companies tend to expunge the older creators - I think part of it is because older creators develop beyond an adolescent mentality. Adolescents want a certain look and feel and style, and when an artist matures they often kind of outgrow that. I hate to say it, but it’s often true. Obviously not everybody does, not every fan or creator fits that assessment, and there is shelf space for more sophisticated drawing styles, more sophisticated storytelling, and more sophisticated stories.

Daniel: That’s an interesting theory.

Norm: It’s not just a theory; it’s at least partly the way things really are. It gets right down to the root of human nature. Why have comics been considered for the young, even today? Have you seen the TV show Who Wants to be a Superhero?

Daniel: No we’ve had it here a couple of times but I’ve…

Norm: Oh my God, it’s awful.

Daniel: And that’s why I’ve not watched it.

Norm: Apparently unintentionally, it shows how adolescently ludicrous the very concept of superheroes are when looked at it from the most general or universal of viewpoints. Because this TV show’s not highly stylistic, it’s just a TV reality game show featuring people making their own costumes and stuff. In contrast, in a comic book you can control all the details and give a kind of idealized impression of the end result. But in reality, a guy running around in a bat costume is going to look absurd. That’s why it’s so hard to do well on film, because it’s fundamentally pretty absurd.

I know you might disagree with me to some degree on this because we’ve discussed it on my message board, but in the last Batman film with Christian Bale, the costume still looked absurd. They did their best to make it work, but they had to go way out of their way. It’s not like it naturally and easily looks cool. It’s a Halloween costume! They have to go out of their way with lighting and camera angles and editing and special effects to make it look as cool as possible because in reality it’s really ridiculous and I think that speaks to the fact that not just comic books but all of Western culture is aimed primarily at the young, and the more refined a sensibility gets, the more mature one gets, the more one starts looking for something that not a lot of others are looking for.

Daniel: Is it a Peter Pan syndrome in that as you get older you lose your childhood and that’s why it’s considered to be juvenile?

Norm: I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with juvenility. Obviously it’s inevitable and I heavily, very deeply cherish my own childhood. But the older one gets the more one wants to see something better. My ideal Batman film, I haven’t even really had much of a chance to think about it, but it would be so low key that it wouldn’t be the kind of thing that would be considered a blockbuster. In my ideal Batman film, Batman would be much more like a ninja, he’d be in the shadows, avoiding most of the pyrotechnics and multiple lighting sources of the present films; it wouldn’t look like a three ring circus. The Christian Bale version got away from that to some degree and maybe the next one will get even further away from that. Hopefully that’s very possible, and I see evidence of it. I’m sure you have, too. Perhaps pop culture mentality, like a group consciousness that we have going with modern electronic culture, is slowly maturing. Kids are savvier than their same-aged counterparts were 20 just years ago. I hope that continues.

You look at the quality of movies that are inspired by comics these days and how radically they’ve changed, just in the last ten years because of CGI alone and because of more serious creators getting involved and making these films.

Robert Downy Jr. is going to be Iron Man. Serious talents are getting involved in these comics’ characters.

Daniel: You look at the latest Batman movies and you’ve got Oscar winners in that. You’ve got Michael Caine, Morgan Freeman, Christian Bale, Liam Neeson and Gary Oldman. It’s not like you’ve got bums running around the place anymore, or one name star like Jack Nicholson and some up and comers. You’ve got all these people, incredibly talented people, lining up wanting to do these. V for Vendetta is virtually a who’s who of the upper echelon of the English acting fraternity. The last Batman film was a stunner, actor wise.

Norm: That’s right. I agree with you that it was definitely the best Batman film yet. The only thing that I liked better about the original Batman film starring Michael Keaton was the music, really. That’s it, there’s very little else I can point to that was any better. The music really was great, though. The same film edited the same way can either fail or succeed for me based entirely on the music, and I never would have guessed that when I was a child. You know, even though some films had such an impression on me, I just didn’t realize at the time that it was the music that was doing it.

Like The Good, The Bad and The Ugly for instance. Did you see that?

Daniel: You’re kidding aren’t you?

Norm: Hah. That’s one of the greatest movies of all time. And at least 50% if not more - probably 80% - that is due to the music. In parallel to that, I think the music of comics is in the storytelling. It’s in Step Three, structure. Music in film functions similarly to what structure or storytelling does in comics; it provides a large part of the rhythm, and just like storytelling in comics, the younger fans don’t recognize just how valuable the music is. They might feel it but they don’t pinpoint it consciously. People are wowed by the flash and the exaggeration and the bright computer colors and the special effects, and they don’t really realize what’s most important in comics or in films which is the rhythm. I know some recognize this, obviously. Everything I’m saying is a generalization.

Daniel: Someone once asked me, ‘Do you know what makes a good artist in a comic book?’ and I said, ‘Well as I’ve been told, a good artist is one that you don’t notice’. You know a bad artist is one where you pick up the book and you notice how bad it is.

Norm: That’s an interesting way of putting it. Frankly, I feel the same way about the general style that came out of Image Comics, to some degree. There are counterexamples, of course. I didn’t feel the same way as strongly about Jim Lee, for instance. But even Lee’s stuff has a similar quality to it; it’s got such a surface gloss that you can see that much of the selling point isn’t really in the heart of what’s most important to the story. A lot of the selling point is just all these little intricate lines and all these glittery special effects on the page.

Frankly a lot of Jim’s figures look kind of stiff and younger fans don’t really recognize it because they’re just wowed by all the complex line work. Give me a Jim Aparo in the early 1970’s, a fluid Jim Aparo figure where it just feels like there’s a stream going of ink or movement going across the page. When I look at Jim Lee’s stuff, it looks like everything is carved in granite, it’s like a stone and it’s just sitting there. Even when they’re in movement, they look basically like they’re sitting there, set in granite. That’s how they feel to me. Now I’m not really dissing on Jim Lee; I’m just meaning to point out the difference between surface gloss and inherent spirit.

Daniel: Did you ever feel that you somehow ‘owned’ Batman, or the other books you worked on, other than your own titles like Metaphysique?

Norm: When I visited DC around 2000, I came to New York to see if there was any available work. It was right after Dan Jurgens had been let go by DC and apparently there’d been an interview that I hadn’t read wherein Dan was miffed by the fact that DC had cut him off (just like they’d cut me off, by the way), and he said something like, ‘They didn’t even so much as give me a...’ I forget exactly how he put it.

Daniel: The gold watch.

Norm: Yeah, and he also said something that gave the impression that he had a sense of ownership for Superman and maybe it was just the impression I was getting from the editors there when I visited and maybe it’s unfair, I don’t know, but I told the editors right at that point that I didn’t feel the same way about Batman, not at all.

I always knew the score from the beginning. I had a very realistic appraisal of my own position with Batman. I knew I didn’t own any part of the character, that they could let me go at any time and that there was nothing that I could really say about it. There’s a tendency to develop a sense of ownership of a character when you put a lot of effort into it. I just never really did that with Batman. I always knew that I was just a hired hand. I put in my best effort, I didn’t let that affect the quality of my work, but I still knew the score and when they let me go it hurt, sure, but I didn’t feel like I had any kind of claim to Batman, no.

Chuck Satterlee: I honestly wanted to write an Ultimate Doctor Strange book, set in New Orleans where I thought he belonged. But Marvel had some unknown writer, who did a little TV show called ‘Babylon 5.’ I think his name was...uh...J. Michael Stracynski. He wrote a Dr. Strange mini, so being an unknown, which I still am, it was nixed. My pitch was not looked at. So, I still wanted to do a book in New Orleans. I'm a fairly religious guy and I love New Orleans, so I put mythology and theology together and set it in New Orleans. And I called up Norm and asked him if he wanted to draw it and luckily he said yes, so it all worked out.[ii]

Daniel: How did you come to work for First Salvo?

Norm: I was approached by Anthony Cannonier and Thad Branco. I was first approached by Thad to do a commission of their main character that I didn’t know anything about. I didn’t know anything about First Salvo at that point either. I just thought that they were a pretty small time operation, I didn’t look into it and I just did a quick commission drawing the character. I think Thad then joined my forum and put a link up to the First Salvo website and I checked it out.

Daniel: What attracted you to work for First Salvo?

Norm: I was looking for work and Thad mentioned the possibility of doing another commission in an email. In the same email he mentioned that he was publishing comics and I asked if he needed anyone else. It’s funny that he didn’t even think to ask me but once I suggested it he was more than happy to have me aboard.

Daniel: He might not have thought to ask you because he might have thought you’d be either out of his price range or busy elsewhere.

Norm: [chuckles] I guess.

Daniel: You are an established artist with a long and illustrious track record.

Norm: That’s true, but if you’re not working for Marvel or DC then it’s pretty hairy out there. More and more independent creators are working for literally nothing. It’s funny because when I first tried to break into comics back in the early ‘80s I would sent stuff to Marvel and DC and in my cover letter I would say, ‘I’m willing to work for free.’ [laughter] It was unprofessional and it’d have set a precedent. But now almost all independent companies have a large portion of their creators working for free. They all have full time jobs and are doing it out of the love for the medium. At least that’s the impression I’m getting. I don’t know how accurate that is, but I expect that it’s somewhat accurate. I can’t afford to do that myself, so frankly…[laughter] Doing a full issue a month is hard work. That’s full time work for me. One or two. [laughter] I’ve been doing two for the last six months or so.

Daniel: The cover for the first issue is some of the best work I’ve seen from you in a long time, and that’s not taking away anything from your other work.

Norm: Thank you. Maybe part of the reason why it’s good is because I did it last. I went through the whole issue doing the pencils and inks and there were a lot of exotic locales and horses and I’d already drawn the cosmic storm in the background, and the characters including the two main ones there and the gun he’s holding. I was sent reference for that gun by Thad by the way. In fact they sent a lot of reference, almost more than any other company I’ve worked for. I didn’t even ask for it, they just sent me the reference. It’s actually really helpful because it means I don’t have to do any of the research myself. So by the time I did the cover I think I had a real feel for the characters, I had just inked the book so it was really flowing out of me at that time.

Daniel: Does it help doing the cover last?

Norm: I guess it depends. Generally I’d have to say that, yes, it would be ideal because it represents the whole of the interiors and if you haven’t done the interiors you’re representing something you haven’t completed yet. In general I’ve always felt that way, that covers are best done last, but it’s rarely that I get to do that.

Daniel: You shouldn’t be getting better as you get older; you should be like a few other artists and just stop drawing backgrounds. [laughter]

Norm: Hopefully not. Some people have maintained their sense of quality all along. Joe Kubert and Neal Adams have sustained the quality of their work for decades.

Daniel: This issue has pages of detail after detail after detail, and then you show a splash page (page 9) that’s just sparse and devoid of background and simplistic. Is it a conscious thing to do when you’re drawing?

Norm: Oh no, that was in the script.

Daniel: Was it full script or Marvel method?

Norm: This was more or less full script, only a few things were changed, but the simplicity of that page was called for in the script. (With page 9) I had a choice to show the desert ground below, in the second panel. They’re not parachuting down, they’re just dropping because they have powers and can just land, manipulate air and other things…it’s a long story. Actually the whole multi-cosmos behind Danger’s Dozen is a big, long story and that’s the trickiest thing for Thad writing this, especially for new readers of these concepts: to have it be reader friendly. The original proposal we were putting together was telling the story in present day terms. This stuff isn’t only multi-dimensional but also historical; there’s a long history with this cosmos. The first proposal was set in the present day and there were so many references and so many things going on and something new and strange in every panel that I just felt lost as the artist drawing it and I could just imagine how the reader might feel. So that was one of the main things that Thad tried to do with this first issue of Danger’s Dozen: to make it much more reader friendly and try to narrow down the concepts and if he references anything that’s not going to be elaborated upon immediately he keeps it to a minimum.

Back to that page (9). I did have a panel design where you could see the ground below but it just didn’t work as well with the dynamic so I left a completely open space behind them. The plane in the first panel, I got specific reference for that from Thad. I’m not used to that; I’m used to doing all my reference on my own. I don’t mind finding my own reference but it does save me time to have that stuff done for me whenever possible.

Daniel: I suppose you’d not need reference for a desert.

Norm: Actually <laughter> it’s funny you say that because Thad did send me reference for the desert to let me know just how flat and plain it is. It’s just flat desert, that’s all there is. There are no dunes; no mountains and he actually sent me a photo of that.

Daniel: What reference did he send for the city on page 18?

Norm: Anthony Cannonier, who is an artist and First Salvo partner, basically designed almost everything. He sent a drawing of the design of Eridue, which is the city on page 18.

Daniel: That page reminded me of a shot from the movie Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, when they come to the city there.

Norm: Oh yeah. I saw that movie but it was a long time ago. I don’t even remember that scene, I’ll have to go and watch it again.

Daniel: On the following page you have some humor with the guy spitting water out of his water bottle. It’s a very cartoonish face which goes at odds with what’s happening on the page, especially with a slaughter going on in the very next panel. Is it a conscious thing to draw something cartoony as that?

Norm: It’s always conscious yeah. That was in the script; ‘One spits out the wine’ <laughter> I can’t take credit for that.

Daniel: As I said, it’s a very cartoonish face, as opposed to the realistic faces you place on other people, even in the same panel.

Norm: Well spitting out wine is intrinsically kind of humorous; it’s kind of like slapstick no matter when you do it or why. So even if it happens when someone is being gutted by an alien, it’ll probably still have a humorous element to it.

Daniel: Thad seems to have a very clear vision with this.

Norm: He sure does.

Daniel: From the sound of things it appears he gave you fairly free reign with the artwork as well.

Norm: The original proposal was done Marvel style and I’d said yes to that, but when we retooled it one of my specifications was that we don’t do it Marvel style, we do it full script. Mainly because, as I said, his concepts are so multi-layered and there’s so much stuff there, for instance, the two main characters in the first issue of Danger’s Dozen, they have pointed ears but their ears aren’t identically pointed and I didn’t even know that. Some of the characters have little details, such as costume details, details about their past that affect the way they’re drawn and it’s very difficult for someone new to the multi-verse that they’ve created, like me, to have all that in the panels, so I asked for a full script for Danger’s Dozen and it’s helped a lot. Besides I prefer full script anyway as a matter of principal because then I can design where the word balloons are going to go. If you work from the plot first it’s a little different. It might be more fun for the artist in some ways but I’ve never really felt that because you don’t know where the words balloons are going to be or how much space they’re going to take up. They can cover up large parts of the design and can even counteract the design that you lay down. So, to me, full script is always superior but then that also depends on having a good writer, somebody who understands comics. If you get a full script from somebody who doesn’t understand comics it can be very much like a prison for the artist. Thad, however, really loves and understands comics and because he’s been creating them for the past fifteen years or so that is not a problem at all.

Daniel: What were the differences between the original concept and this story?

Norm: Just a matter of setting and time. The first issue of Danger’s Dozen is set in 1945 I believe, just at the tail end of World War Two. The original presentation was set in the present day. That made a big difference.

Daniel: Whose idea was it to alter the concept?

Norm: The main reason it was changed was because the original proposal was presented to Image Comics and Erik Larsen did not like it. So Thad was asking for everybody’s opinions around him, including me and the other creators, and all of us pretty much zeroed in on the same thing, the complexity of the thing for a new reader. It was just too complex and there was just too much going on. That’s why he came up with the second concept which I think works much better. It’s more reader friendly than the original.

Daniel: This must be one of the few times I’ve ever seen you draw a camel.

Norm: Yeah, I probably did a couple of them in Birth of the Demon, but I know I drew some horses there. In fact I pulled them out when I was gathering reference for this issue and I realized, <chuckles> most of those horses I drew are not…I can’t use them for reference. They’re not good enough and frankly I think I’ve gotten better and I think the horses in this issue are much better. I had better reference material this time around too. Horses aren’t something I can draw off the top of my head as well as I can draw the human body, so I need reference for them. By the way, First Salvo didn’t provide my horse reference; I did.

Daniel: Every artist has told me that horses are hard to draw. There’s an old trick of drawing a horse in long grass so that way you can cheat and only draw the head. <laughter>

Norm: I remember when I was having dinner with a bunch of other creators at WonderCon in around ’92, just after Birth of the Demon had come out and among other people there was Joe Kubert. He had seen it and I pressed him for an opinion. He said that he’d liked it and I pressed him for something constructive, some criticism and that was the first thing he zeroed in on, the horses. I didn’t think about it much at the time but looking back on it he sure was right. I’d like to know what he thinks of my horses today.

Daniel: Have you started work on issue #2?

Norm: Not yet. It’s been two or three weeks per issue, then I switch over to Of Bitter Souls and do an issue of that and I have some other clients as well. In one week I’ll be starting the second issue of Danger’s Dozen.

Daniel: How many issues has Thad scripted out for you?

Norm: He’s plotted out the first four or five I believe. I’ve only received the full script for the first issue.

Daniel: It looks to be an on-going concern and not a limited series.

Norm: Right. It’s been on-going for a long time. This is the same universe and the same characters that First Salvo has been publishing for the past fifteen years. It’s always been on-going; this is just a relaunch to get the greatest interest.

Daniel: First Salvo have put together an impressive collection of artists; Mark McKenna, Bob Almond, Sal Velluto, Jerry Ordway, Ron Frenz, Pat Ollife and Joe Rubenstein. Do you think there’s any chance that we might see someone such as McKenna, Almond or Rubenstein inking your work?

Norm: I think everybody knows by now that I prefer inking my own stuff but it’d be neat seeing another inker after all this time and I’ve always appreciated Joe’s inking so I don’t have a problem with his inking my stuff. The main problem would be that it hardly takes me any more time at all, if any, to ink my own pencils than it does to do full pencils for an inker. I ink my pencils on a light box and my pencils are done four by six inches, they’re basically like large thumbnails, or small roughs, and they’re detailed enough so that I can just enlarge them on a photocopier, put them on a lightbox and then ink them that way. But if somebody else is inking my pencils I have to take those thumbnails and do a full sized drawing and that’s the time I would be inking. So I don’t really gain anything by having somebody else ink my pencils. I don’t gain any time and, of course, I like doing it all myself anyway.

[i] Since this interview was conducted the Disney Corporation bought Marvel.

[ii] Catching Up With Norm Breyfogle And Chuck Satterlee by Edward Carey; October 10, 2006, http://www.comicbookresources.com

Next: New Light Through Old Windows.