Norm Breyfogle (Auto)Biography: Coming Home: 1996 – 2003

"At that point Norm became more trouble than he was worth."

Coming Home: 1996 – 2003

Conversation with Norm, plus contributions from J.M. DeMatties and Rick Veitch.

Once Malibu was free from Image and began enjoying their own success, several other publishers begun to make overtures to purchase the company. Rosenberg entertained several offers before deciding upon Marvel Comics. The decision was made partly due to a pre-existing relationship between Rosenberg and Marvel’s then owner, Ron Perlman, and also due to the high profile that Marvel enjoyed in the industry. What wasn’t well known was the fact that Marvel, despite appearances to the contrary, was hemorrhaging cash at a great rate and was verging on the brink of bankruptcy. Increasing competition, the loss of company assets in the form of artists such as Lee, Liefeld, Larsen, Valentino, Portacio, Kewon and McFarlane to Image, and others, such as John Byrne and Frank Miller to Dark Horse, along with a glut of sub-standard titles (in an effort to saturate the market) and the reduction of the direct market had all conspired to reduce Marvels profit flow and severely undermine its foundations. What the Malibu staff wasn’t aware of was the mass firings that were already going on at Marvel.

Each time a new round of firings began the word from the upper level management was that it would be the last. Morale was at an all-time low and the nature of the dismissals resulted in some long time staff members being handled poorly. Throughout all of this Malibu kept publishing their titles with success.

Marvel subsequently increased the cover price on all of its titles and those of Malibu’s. Rosenberg was concerned enough to begin to petition Marvel over their handling of the overall situation and his concern for the Malibu personnel. Marvel responded by beginning to integrate the Ultraverse with the Marvel universe via a series of crossover’s. One result of this saw Norm being tapped to draw a Prime/Captain America annual, the first time he had drawn the character since his Marvel debut in 1985. That book marked the last work Norm would do for Malibu. Rosenberg was then advised that Malibu would also have to shed staff in order for Marvel to survive. Malibu employees offered to take a decrease in wages, but Marvels then management was insistent so staff were dismissed. Rosenberg then left Malibu/Marvel both in disgust and in protest about the way staff had been treated. Once Rosenberg had left Malibu the line of titles were quietly wound up and the characters retired, seemingly forever.

Fortunately for Norm he fully owned Metaphysique and as such it didn’t suffer the same fate as Prime and the rest of the Ultraverse. When asked about the Malibu characters in 2005, Marvel Editor in Chief, Joe Quesada replied, ‘Let's just say that I wanted to bring these characters back in a very big way, but the way that the deal was initially structured, it's next to impossible to go back and publish these books. There are rumors out there that it has to do with a certain percentage of sales that has to be doled out to the creative teams. While this is a logistical nightmare because of the way the initial deal was structured, it's not the reason why we have chosen not to go near these characters, there is a bigger one, but I really don't feel like it’s my place to make that dirty laundry public.’[i]

Quesada’s claims have been publicly challenged, in part, by several of the Malibu creators, including Prime creator Len Strazewski. ‘As far as I know,’ said Strazewski, ‘there is no dirty laundry to speak of.’ ‘As for it being a 'logistical nightmare' to pay creators a percentage of a character usage,’ adds James Hudnall, ‘if Malibu could do it I don't see why it would be so hard for big bad Marvel... I have no idea what Quesada is talking about when he said there are some other issues. They bought the Ultraverse free and clear. They had no problem doing Ultraverse comics for a couple of years after they did that. I would love to know what he's talking about.’[ii] ‘Marvel just isn’t interested in publishing those characters,’ said Norm, ‘I heard that they just don’t want to pay the creators of the Ultraverse a certain percentage every time a character is published.’

For whatever reason Marvel have resisted both internal and external demand to resurrect the Malibu/Ultraverse characters and have indeed taken steps to remove all reference to the characters from their publications.

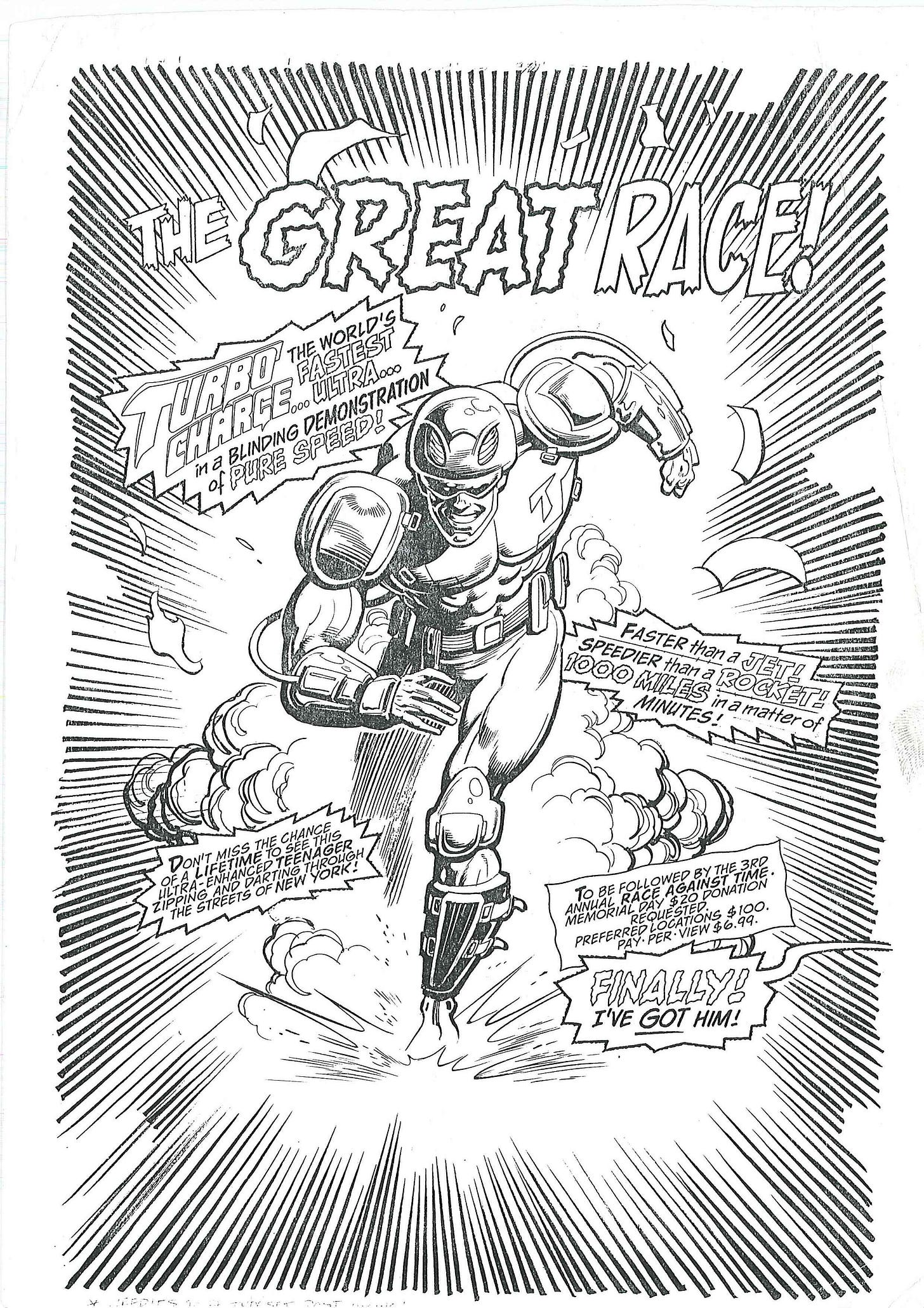

With his Malibu obligations finished Norm was thus free to seek employment elsewhere and was quickly snapped up by Valiant/Acclaim and assigned the book Bloodshot. ‘Bloodshot’s another example of a character that I didn’t really feel that I would necessarily want to do,’ Norm said at the time, ‘but I ended up enjoying it a hell of a lot. I’m drawing the last issue right now, and I’m going to hate leaving it. He was a lot of fun. I got a chance to expand my visual repertoire a bit, because I’ve never really drawn any big guns or anything like that… it was also a bit of an education, and I think I’m getting better at it!’ [iii]

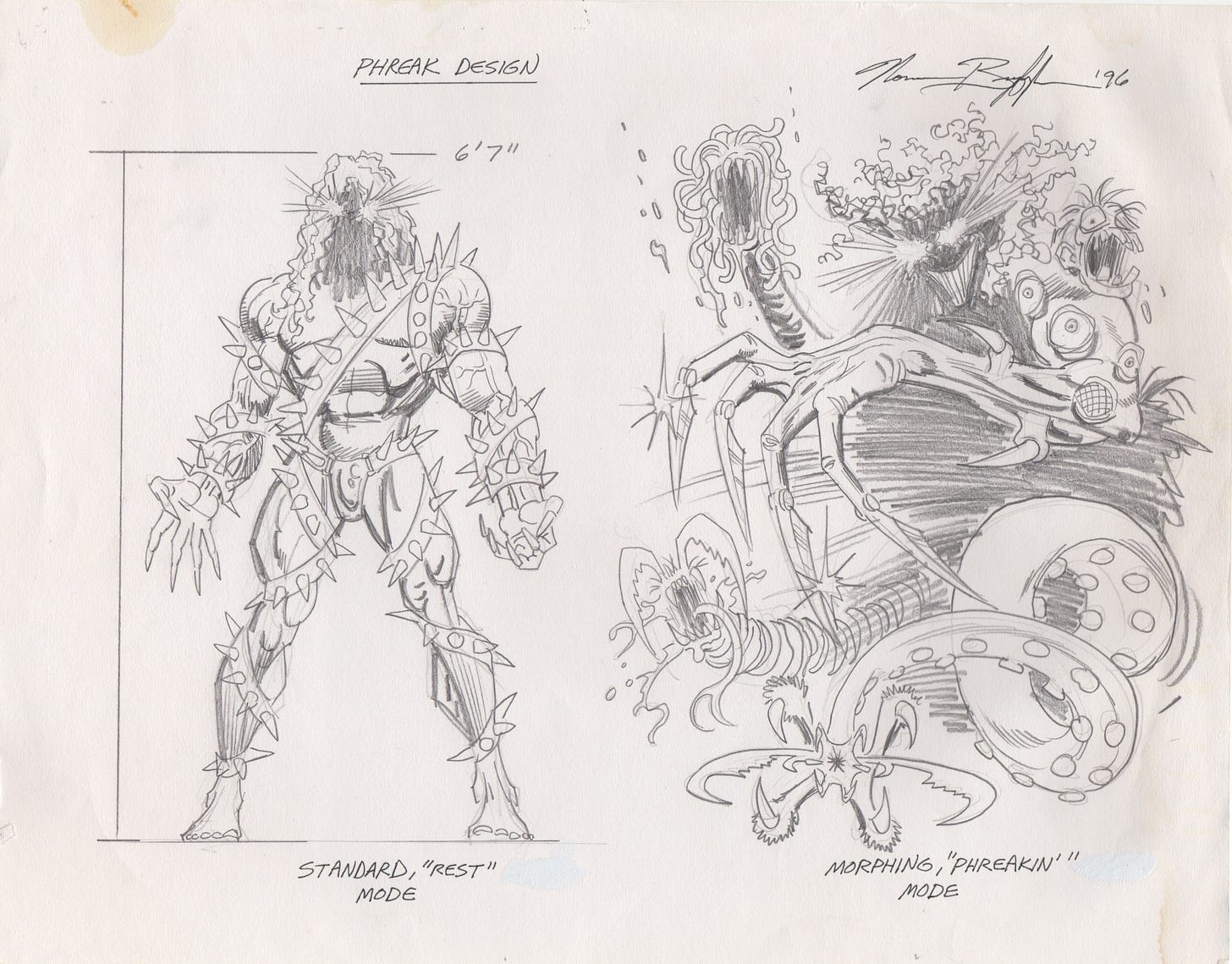

Working with writer Jesse Berdinka, Norm developed another new character for Acclaim. Sadly it would never see the light of day. ‘I designed the character and came up with the first cover,’ said Norm at the time, ‘He’s a very different character – he even looks very different – but that’s about all I can say at the moment. The first issue will be out in August, I believe, and it looks like it will be for their Valiant line. There are some things coming up that I can’t really talk about, but… I might be involved with a number of creators that will be challenging the present status quo of publishers and creators in a new imprint. Beyond that I can’t say anything.’ Shortly after that statement Acclaim, which had been struggling since their revamp, cut back on their line and would eventually cease publishing comic books for an extended period of time.

Once Norm had finished with Acclaim he then returned to DC, reuniting with Alan Grant for the fiftieth issue of Batman: Shadow Of The Bat. The reunion was further extended when DC commissioned a four part mini-series featuring Anarky, the character that Grant and Breyfogle had created and introduced in Detective Comics. The series was successful enough for DC to further commission a regular, on-going series from the pair. Sadly the series wasn’t a lasting success. Beginning in May 1999, the series lasted a mere eight issues and was cancelled by December 1999. A further two issues were scripted and penciled, but these remain unpublished by DC. The status of Anarky in the DC Universe is largely unknown with the character being largely ignored since both Grant and Breyfogle ended the series.

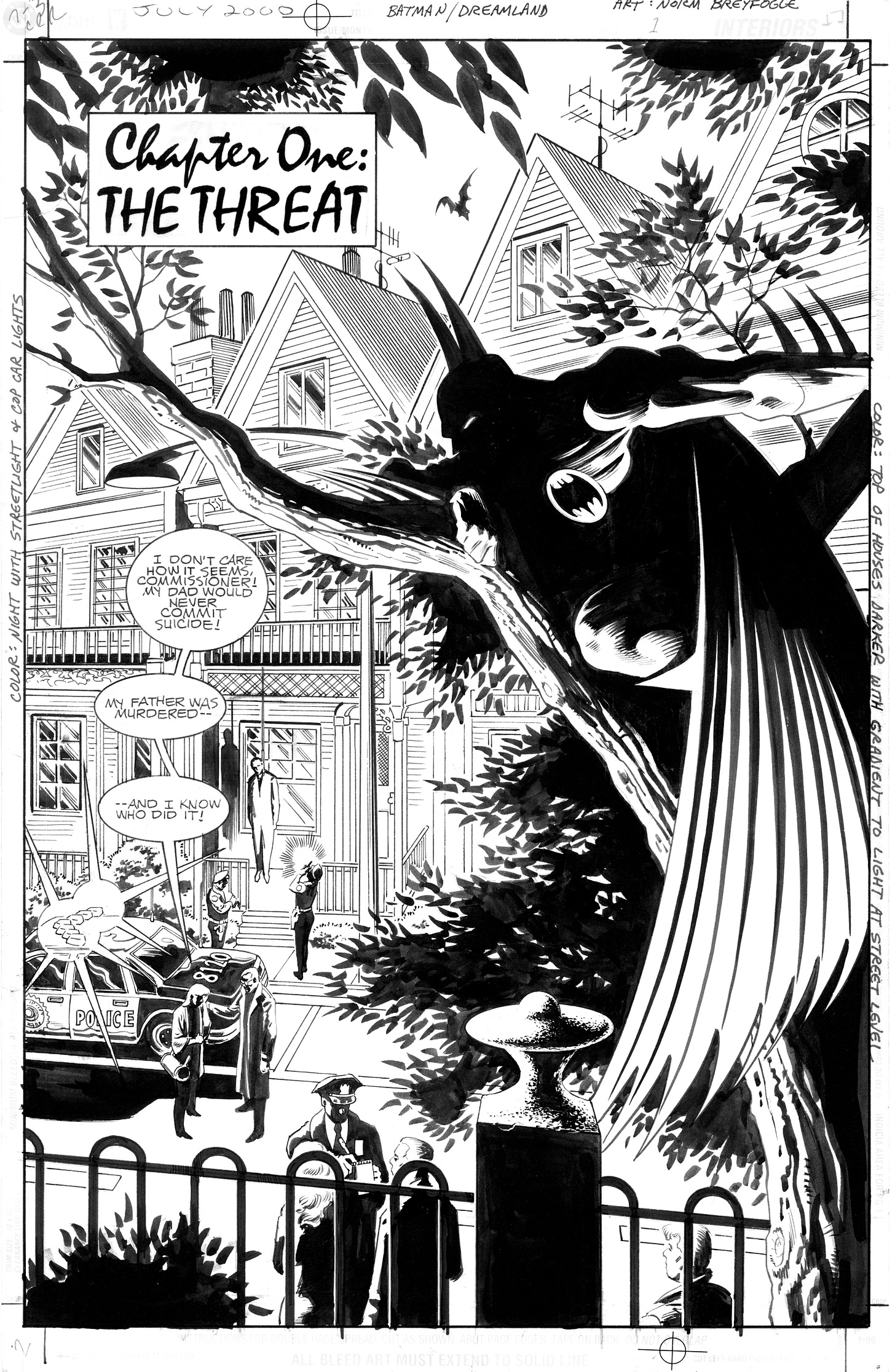

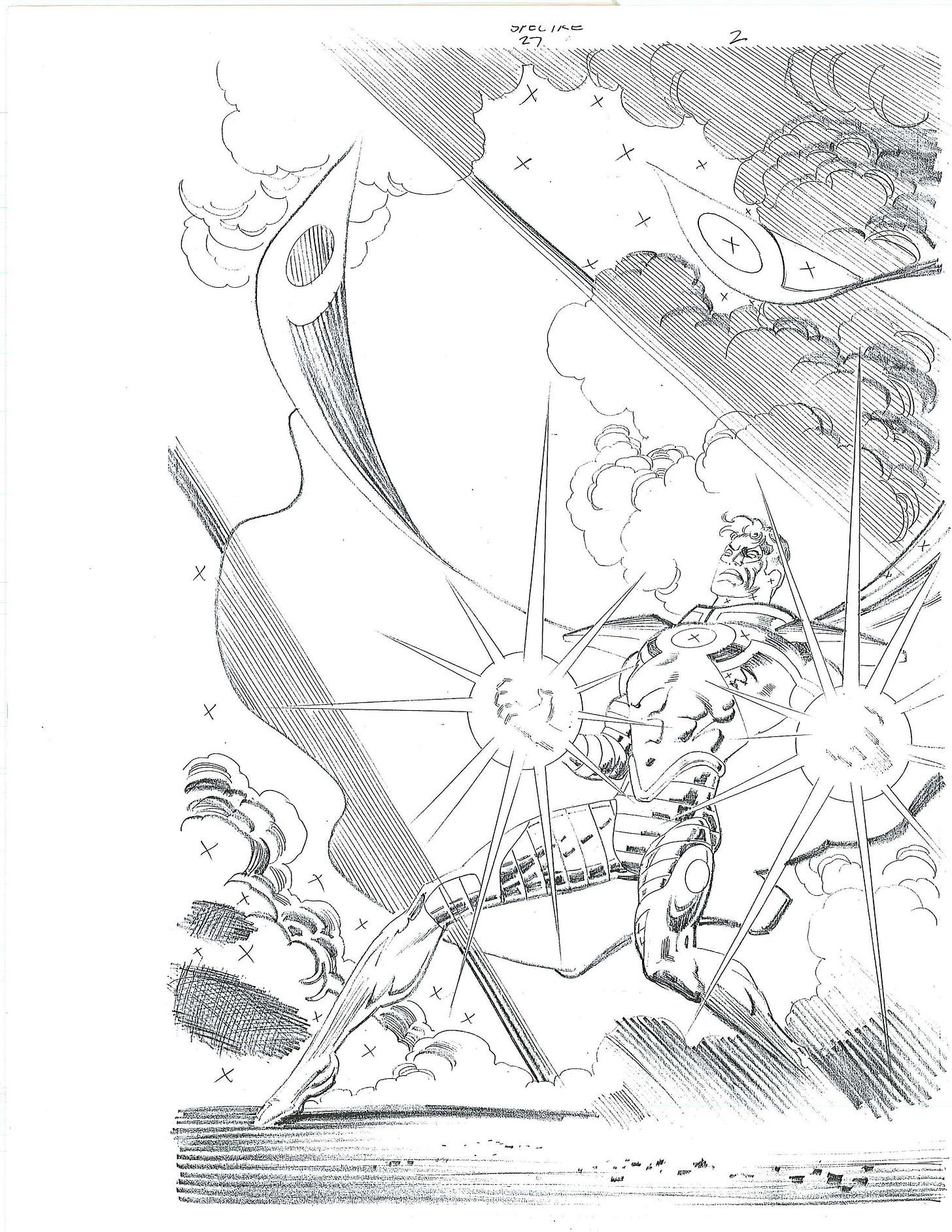

While at DC Norm began to work on titles as diverse as Hawkman, Lobo, Superman, Wonder Woman and Catwoman. The latter two were of particular interest as Norm inked industry legend, Dave Cockrum, on one of his last comic book related jobs and also inked noted ‘Bad Girl’ artist, Jim Balent, on Balent’s signature title, Catwoman. Norm also penciled the three issue Elseworld’s series, Flashpoint, an alternate telling of the story of The Flash and this, along with other one-off issues such as Green Lantern: Circle of Fire, would see him doing steady, non-Batman related work, for DC until he also pitched an original idea featuring Batman to DC with Alan Grant attached as co-collaborator, which was accepted, resulting in Batman: Dreamland. Sadly this one shot would mark the last time that Norm drew the character that made him famous in a sole book, with the exception being Batman being featured as a supporting character in a Green Lantern tribute to Julie Schwartz issue in 2004. Along with Alan Grant, during his second stint at DC Norm was fortunate enough to work with yet more visionary writers, notably Rick Veitch on Aquaman and J.M. Dematties on The Spectre.

Anarky Farewell

Anarky's cancellation might laughingly tempt conspiracy theorizing. After all, the main character's views are potentially politically sensitive. And you should see the two issues that were already completed but will now never see print! (I'll just say two words: ‘East Timor’.) When all the smoke clears, however, the marketplace, for good or ill, whether manipulated or not, rules the roost.

Ultimately, unless proven to be factual, conspiracy theories are just mental exercises. They are fun or unnerving, depending on one's attitude, but generally ineffective for real social change. This is why Anarky, though often thought-provoking, is mainly just plain fun. He can fulfill the theorist's fantasy of acting in situations where we normally feel so impotent.

Alas, the topics Anarky addresses with such wish-fulfilling effectiveness may be somewhat unsuited for certain genres. The obvious trend for many ‘blockbusters’, with some exceptions, is toward more escapism and less social relevance. An alchemical mix of the two is far less commonly successful. For those who DO want anti-establishment politics in their comics, super-heroes may seem a bizarre venue for it.

Anarky is a hybrid of the mainstream and the not-quite-so-mainstream. This title may have experienced exactly what every ‘half-breed’ suffers: rejection by both groups with which it claims identity. Certain young aggressive bulls prefer straight energetic power-fantasy (a large part of the super-hero fan base.) These turks may be bored by anything even remotely resembling a political manifesto. Others write off the super-hero genre as intrinsically juvenile. I personally enjoy full integration of both modes, but if Anarky's cancellation is any indication, I'm possibly in a minority.

The battle lines between ‘escapist’ art/culture and ‘relevant’ art/culture were drawn long before Anarky was even conceived. Any character not immediately fitting in snugly with either faces an uphill battle. It requires time to build a fan base, something a periodical business is not liberally willing to put to risk. Alan and I knew from the beginning that Anarky probably wouldn't last in this environment.

But cheer up, Anarkists. Anarky is not ‘really’ dead. He's still in the DC universe. He's still camped out underneath the Washington Monument. He's still hunting down, exposing, and ostracizing the shadier and more taboo villains that the other super-heroes generally fear to touch: those parasites cloaked in the guise of the respected elite. View his absence from comics pages not as an extinction but as symbolically fitting. After all, if someone were really exposing corruption in high places, would his adventures be available in a monthly forum? Superman may be dramatically saving the planet from destruction (and more power to him; I'm a fan) but I consider Anarky still working to make this a better, freer, and more just place to live. Consider him on a highly secret case, and we just don't have a ‘need to know.’

And every now and then, maybe an adventure or two of his will see the light of day...[iv]

In 2001 Norm split with Mike Friedrich as Friedrich slowly began to move away from artist representation. Friedrich recently looked back on his time with Norm and had this to say when asked how he had seen Norm's art develop over the years, ‘His figures and faces became more developed and better drawn, along with a bolder inking approach. He designs a panel and a page to grab your eyeball and keep it moving.’ Asked for strengths and weaknesses in Norm’s art Friedrich felt that the strongest aspect of Norm’s art lies in his storytelling, his weaknesses, in his view, lies in his range of facial expressions. In closing Friedrich added the following, ‘He defined ‘Batman’ for the late '80's and early ‘90’s. He launched ‘Prime’ with even more excitement than he had brought to ‘Batman’. Unfortunately industry and readership tastes constantly change and he eventually was treated as ‘ho-hum, been there, done that’ and fell out of favor. I'm sorry that happened, because he had then and still has a lot of talent. I greatly enjoyed representing his business interests for the time that I did.’

At the same time work began to dry up at the major companies. In response to this Norm, in 2001, wrote a series of letters to the Comic Buyer’s Guide questioning the hiring practices of both Marvel and DC and in particular the trend to hire younger, unproven, talent over established professionals. These letters were not received well amongst editors at Marvel and DC and it led to Norm not being offered any further work at Marvel. When this response was questioned a senior editor at Marvel offered the following reply.

Every editor is looking for creators who can make his titles sell. Whose work he likes, and who are easy to get along with. Norm hadn't had much luck cracking Marvel until the Thunderbolts and Avengers Annuals, and the Hellcat limited series. And the response to them was all right, but we didn’t have anything else for Norm immediately thereafter--as you can see, all of those books would have been additive to our publishing schedule. As we tend to do in situations like this, we told him we'd keep him in mind if anything came up down the road.

Not long thereafter, we began receiving letters from Norm, which were sent not just to me, but to Joe Quesada, (then) Marvel President Bill Jemas, and the Comic Buyers Guide, basically accusing Marvel of having an organized conspiracy in place to lower costs by eliminating the veteran artists in favor of newer talent which could be hired more cheaply. Now, that's a patently absurd statement, as anybody who looks at our output over the years since Hellcat can attest. But we expected this was all part and parcel of the way Norm was feeling towards the industry at that point, suddenly finding it hard to get assignments after years of regular work.

Nonetheless, the reaction of folks who read these letters (and there was more than one--the CBG printed them for three or four issues running) was A) what is this crazy guy talking about? B) Why does he think he's owed work, especially when he's only done a handful of jobs for us, and C) Even if we did give him work, is he stable enough to get through it, or will he wig out like this the first time a problem shows up?

At that point Norm became more trouble than he was worth. We have enough problems putting out all the titles we do a month--we don't need creators doing big flip-outs and running to the media and Marvel's bosses whenever he's unhappy. Given that none of the editors at Marvel had hired him before this, my guess is that this became the thing for which Norm was known to them--not a ringing endorsement when considering an artist for an assignment--or they didn't notice at all, in which case things simply continued as they had been.

The absolute reality of this business is that absolutely nobody is owed work and you have to prove with every job that you're the best guy for the assignment, better than everybody else in the industry and better than all of the young artists clamoring to get into the industry. There's no point where you're ‘safe’, where you can just sit back and cruise, content in the knowledge that there'll always be work. It's unfortunate, but that's the reality. So you've got to constantly be working at your craft and at being desirable to the people doing the hiring. And even if you do that, there's no guarantee things will work out. This industry is littered with the bodies of people who once worked in it but were kicked to the curb at some point (editors as well as artists and writers).[v]

Norm was told, bluntly, that, if he was to work for Marvel again, he’d have to supply samples of his work and be prepared to accept a page rate that was equal to that of a novice artist breaking in. He’d also have to remain silent on certain subjects. This was despite decades of work, on high profile jobs, and Norm’s most recent Marvel work being a few years old.

This virtual blacklisting also extended to writer Alan Grant, who had also become very vocal in what he perceived as ill treatment from editors.

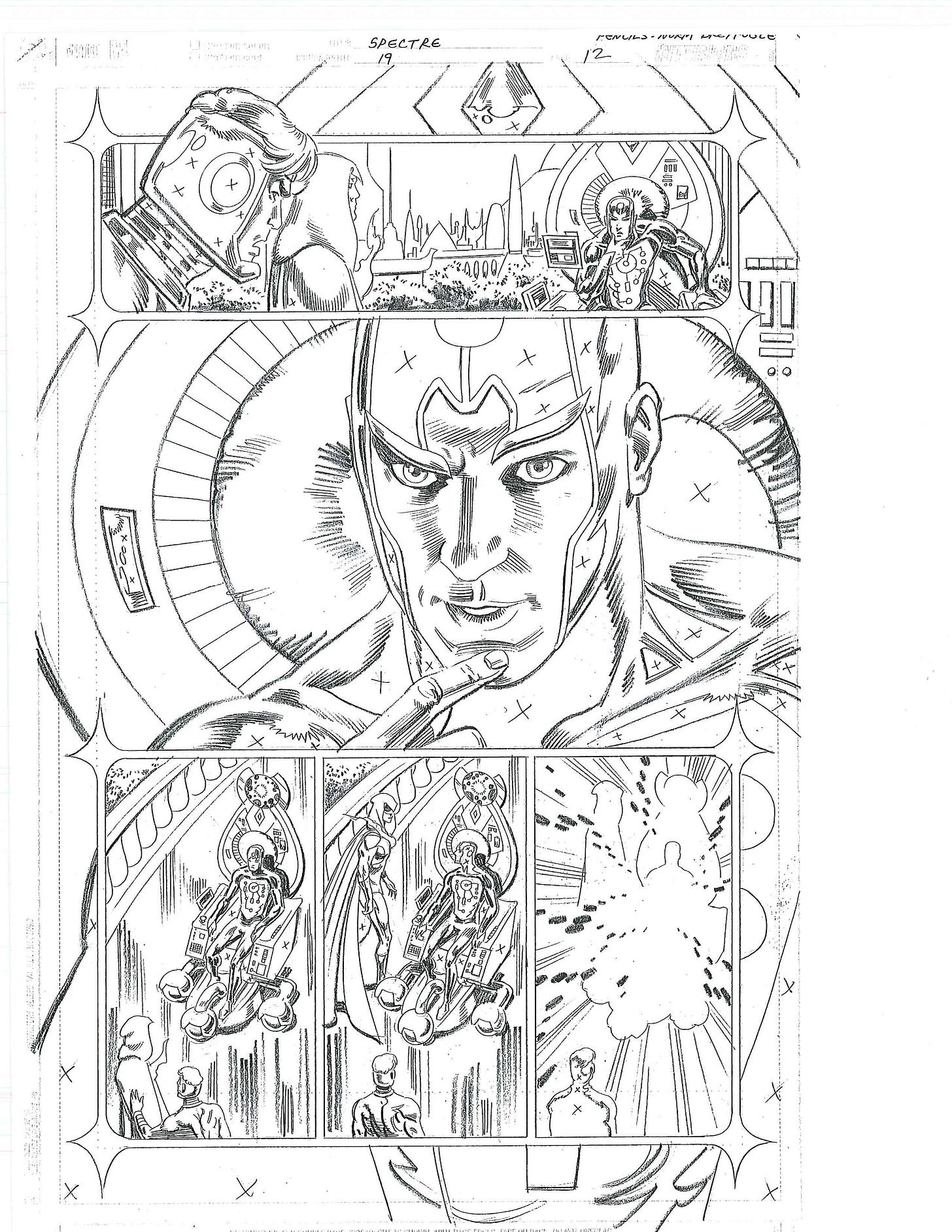

Despite the treatment towards Norm from Marvel, he was assigned regular penciling duties (with inks by Dennis Janke) for an extended run on DC’s Spectre, a title that suited Norm’s expressionistic approach of the time. Writer J.M. DeMatties was delighted to have Norm as the regular penciler, and as such began to experiment with more expansive storylines, which suited Norm down to the ground. Norm’s Spectre work was well received and its unique style was welcomed at the time, and, as with Mitchell and Batman, Janke’s inks only served to enhance what Norm had penciled, rather than overpowering it. Norm’s art during his second stint at DC was handled by a number of different inkers, including himself. In a rare opportunity Norm was able to see his work inked by artists such as Klaus Janson, Scott Koblish, Kevin Nowlan, Norm Rapmund and Sal Buscema, amongst others.

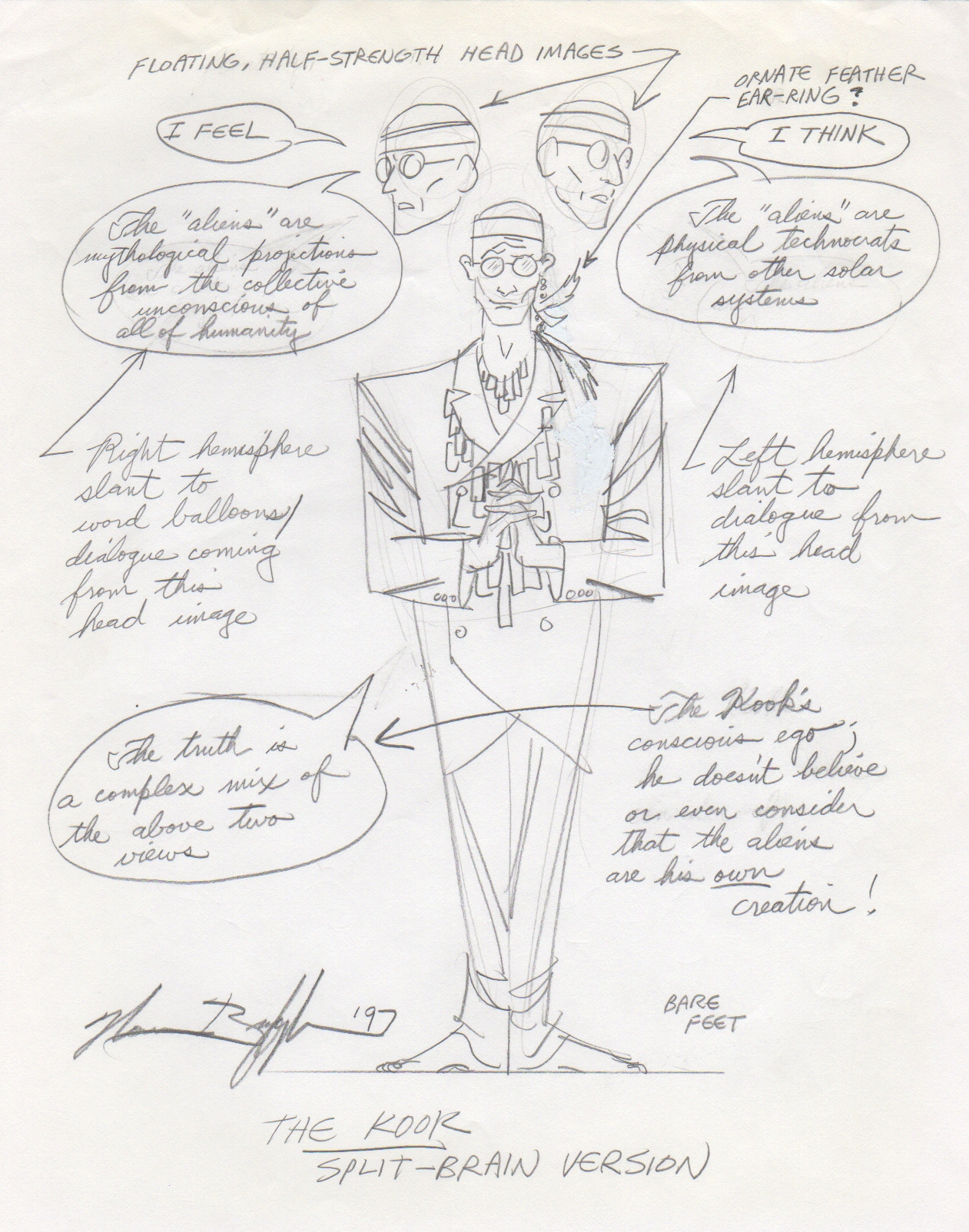

Two projects, Batman: The Abduction and Batman: Dreamland marked another personal milestone for Norm. The idea for the first story was born out of a series of faxed exchanges between Norm and Alan Grant, whereby they would debate politics and philosophy, and after one discussion turned towards UFOs the germ of an idea was planted and Norm ran with it. Creating a new character for the project, The Kook, Norm and Alan co-plotted the story and Grant wrote the final dialogue.

‘I co-plotted both books,’ said Norm, ‘but only got credited with co-plotting the sequel (‘Dreamland’). The lapse was a mistake; I'd been told I'd be credited with co-plotting both books, and I received an apology from Denny O'Neil when I wasn't credited on ‘The Abduction’. The Kook was a simple character based generally on UFO ‘experts,’ but yes, I did ‘create’ him more or less alone…including his name.’

The Kook was an extension of Metaphysique, both in outlook and powers. ‘Basically, he’s a transformation of my own character, Metaphysique.’ said Norm at the time. ‘It’s like Metaphysique as seen through a much more skeptical filter. That’s why he’s called the Kook.[vi]‘ The story, which revolved around alien abductions, went through many changes, at one point Superman was involved, but soon discarded as a story involving aliens wouldn’t have worked with an alien as the main character. Dreamland was a sequel to The Abduction and was also co-plotted by Norm and Alan Grant. Norm also painted the cover and this marked his last complete Batman story.

Daniel: You co-plotted Dreamland and Abduction. Lots of artists never even get to that point. I've spoken to a few who say they only ever drew what was in the script and had no desire to write.

Norm: I know. I was motivated; I was digging up work, and DC was showing the first signs of letting me go. I was in fact working on ‘Dreamland’ when I got my strange phone call from Mike Carlin asking me out of the blue if I was a ‘team player.’ Even though he was the Editor-in-Chief, he seemed very surprised that I was inking it myself, and then he had a thousand nitpicks regarding my inking techniques. I look back on that job now, with ten years objectivity toward it, and I now consider it the very best inking I have ever provided for DC!

Daniel: It's some strong inking, and when you compare the inking on Dreamland to the ink job on Abduction, which was very heavy indeed, Dreamland did prove, or should have, that your best inker is indeed yourself.

The concept behind Dreamland seemed very much more of yours than Alan’s.

Norm: Well, yeah; it was my idea. I guess I was proud of that. But still, alien abductions were all over various TV shows; it seemed an obvious idea to me.

Daniel: I kind of had a problem with it at the time because Batman seemed surprised at the aliens, yet the DCU is full of aliens, some of which are his best pals.

Norm: You keep saying that, but to me, the aliens behind abductions were very different than the known aliens in the DC universe. Still, your driving that point home for me makes me remember that I did kind of consider it an Elseworld's-type story, though not officially so. The way I figured it, the mystery behind the abductions would be an ideal exercise for the World's Greatest Detective.

And the more I recall it, the more I realize that I did contribute a lot to that story. One most crucial example: Alan wanted Batman to just appear inside ‘Dreamland’ (Area 51) with no explanation, but I felt that credulity stretched a bit too far, and I insisted that we show how Batman actually breaks in. I even suggested the EMP device to kill all the electronics in a small area.

Rick Viech: (On working with Norm on Aquaman Secret Files 2003) … Just great. When I got his pencils back for the script I was jumping for joy, because he really got what I was trying to do and made it work beautifully. I wish he'd been the regular artist on the whole series. What I liked best in working with him, beyond his utter professionalism, was his story telling ability. I'd been a bit frustrated with some of the younger artists who tend to ignore any sort of panel direction and load up the pages with superheroes just standing around looking tough. I'm old school, in the sense I want those characters to act and do things that give depth and meaning to a story. Norm is right there. He understands how to interpret a script and use the action and characterization to tell the story in an exciting manner.

J.M. Dematties: (On working with Norm on The Spectre) Our editor, Dan Raspler, chose Norm for the assignment. I wasn’t aware of all of Norm’s work, but I was certainly familiar with his Batman tenure—and so I was delighted when Dan told me Norm was coming on to The Spectre. I was even happier once we started collaborating. It was a collaboration I still look back on fondly.

Norm is a thinking artist—someone who’s not just concerned with what he’s drawing, but with the entire story, from every vantage point. He sees into the story, has challenging questions, and explores things philosophically and emotionally. He was perfectly suited to a book like Spectre, which dealt with the metaphysical on a monthly basis. I loved our conversations about the stories as much as I loved seeing the finished pages.

What I love about Norm—and this is going to sound funny—is that, when he draws a story, it looks like a comic book. What I mean by that is that Norm brings all the energy, dynamism and emotional power to the page that we’ve come to expect from the best mainstream comic book artists. His work flow, leaps, explodes across the page. I still remember one Spectre issue in particular where the Spectre was manifesting to a crowd of people at the U.N. Norm drew this incredibly dynamic scene. Looking at that page, I felt like a ten year old kid again, sprawled out on the living room floor, reading my favorite comic. Not many of artists—even some of the truly brilliant ones—can do that for me. Norm’s work gets to the heart of the traditional American comic book experience—and yet the perspective he brings to the work is completely modern. It’s a wonderful combination.

Norm’s last work for DC was an eleven page Green Lantern story, published in 2004, starring Superman, Wonder Woman, The Flash and Batman, in a special Julie Schwartz tribute issue. This story was inked by industry legend Sal Buscema and showed that Norm had lost none of his touch as an artist.

Over the years Alan Grant and Norm had been invited to submit proposals for Batman stories as public interest increased. Each time the proposals would be rejected, the final proposal coming in 2006 with an idea that Grant ranked amongst the best he’d ever had. Norm also submitted ideas of his own and in conjunction with other writers, each time he was knocked back. The knockbacks weren’t limited to sole DC projects.

Dark Horse, when pitched a Batman/Tarzan crossover with DC, assigned Norm to draw it. This request was rejected by DC editors. The artist on the project was Igor Kordey.

Norm also spent time working with other artists and writers on various proposals, including a Coyote proposal for DC with Steve Englehart, a submission of Phantom art samples for King Features with artist Joe Rubenstein and many more, including a Batman proposal with the author of this book.

None of the proposals or samples would lead anywhere.

[i] http://www.newsarama.com/JoeFridays/JoeFridays9.html, Joe Fridays - Week 9, Newsarama, 2005

[ii] Lying In The Gutter, June 28th, 2005 http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=14961

[iii] Stormin’ Norm by Paul Birch

[iv] http://www.normbreyfogle.com 1999

[v] At Norm’s request, I have chosen not to name the senior editor at Marvel who sent that email to me. I did pass it on to Norm who replied, at the time, ‘I expect no less nor no more from him. It does back up my claims of being blacklisted.’

[vi] Bats goes for the ride of his life by Brad Cook

Next: Norm goes independent.

I’m certain it’s a result of the vintage of the first life of manuscript, but the ways that this chapter talks about DREAMLAND as the last Breyfogle Batman story (or even the last Grant/Breyfogle Batman story) doesn’t take into account his BATMAN BEYOND work, nor the pair’s BATMAN RETROACTIVE one-shot, both of which were some of the best output of his final professional years.

I know you know, and I don’t mean to be a pedant. I remember despairing in the mid-‘00s that maybe that was all they wrote for Norm, and hoping that his song would come around again. I’m so glad it ultimately did!

Thanks again so much for putting this bio out into the world!!

Query, Daniel, anyone: Where does the Heroes World debacle/shit show/disaster fit into the Malibu timeline at top of the post?

And FWIW, Tom Brevoort has repeatedly strongly implied that there’s some sort of problem with using the Ultraverse characters. My Spidey sense says that theirs is some sort of creator share thing involved. Now, why that would be a problem, if it is, would be pure speculation on my part, obviously.

Now, part of my sussing is that I cannot believe that there’s *no* interest in, as we say in the 21st century, Marvel exploiting the IP — nose smiting face and all that.

INSTANT UPDATE: My AI chatbot of choice hypothesized (!) or implied that the problem maybe isn’t the creators but the deal with Rosenberg:

https://g.co/gemini/share/3f84ec956c59