Norm Breyfogle (Auto)Biography: Breaking In: 1980 – 1987

"You know I actually considered becoming a trucker."

Before we start the next chapter, I’d like to address the number one question I’ve received since starting this series: Is there going to be a print edition of Norm’s (Auto)Biography?

The short answer is, I’m not planning one.

The long answer is this. I do have my own publishing imprint, and I can do it, but I’m not thinking that far ahead right now. There’s a lot of pain behind this series, it seemed cursed for a while, as you can read in the first installment. I’d love to see a print edition, but I have two projects on the plate right now which are well advanced and need to be finished before I start.

There’s also another issue that I have to deal with. As you’re going to read, this series was completed when Norm was still alive. I’ve not touched it, other than a quick edit for spelling and to change the tense. To get a print edition out there means working on the manuscript - which I believe I can do. It also means I have to write the final chapter. And that I really don’t want to do.

Norm wouldn’t want anyone feeling pain about his loss. He’d want people to be happy, to celebrate him and enjoy the work he left behind. This doesn’t change the fact that what happened to Norm was utterly senseless. It left a massive emotional wound that hasn’t fully healed. When someone passes through a long term illness, or age, you can deal with it. The way Norm went was simply not fair. He deserved better.

To put it bluntly, I’m not quite ready to write that last chapter just yet. Ask me the question again when the series is ended - and I’ll be keeping it up and open, for free, unlike other parts of my archive. It’s what Norm would want.

By all means, ask me any question about Norm and I’ll do my best to answer them.

Now, onto the good stuff.

Breaking In: 1980 – 1987

Conversation with Norm, plus contributions from Mike Friedrich.

Throughout his childhood and adolescent years Norm kept drawing. He would produce entire comic book stories, written, penciled, inked and lettered, with encouragement from his mother. In 2008 some of these stories were gathered together and privately published by Norm as a sketchbook and printed in limited numbers and offer an insight into Norms formative years. The stories show a developing artist whose abilities in being able to tell the story as opposed to having flashy art was clearly evident.

At the age of thirteen, with the encouragement of his high school art teacher, Norm’s mother enlisted the services of a commercial artist and teacher in the area, Andrew Benson, to train him and teach him art. Norm spent the bulk of his Saturday mornings receiving private lessons in design, technique, anatomy and penciling and inking skills.

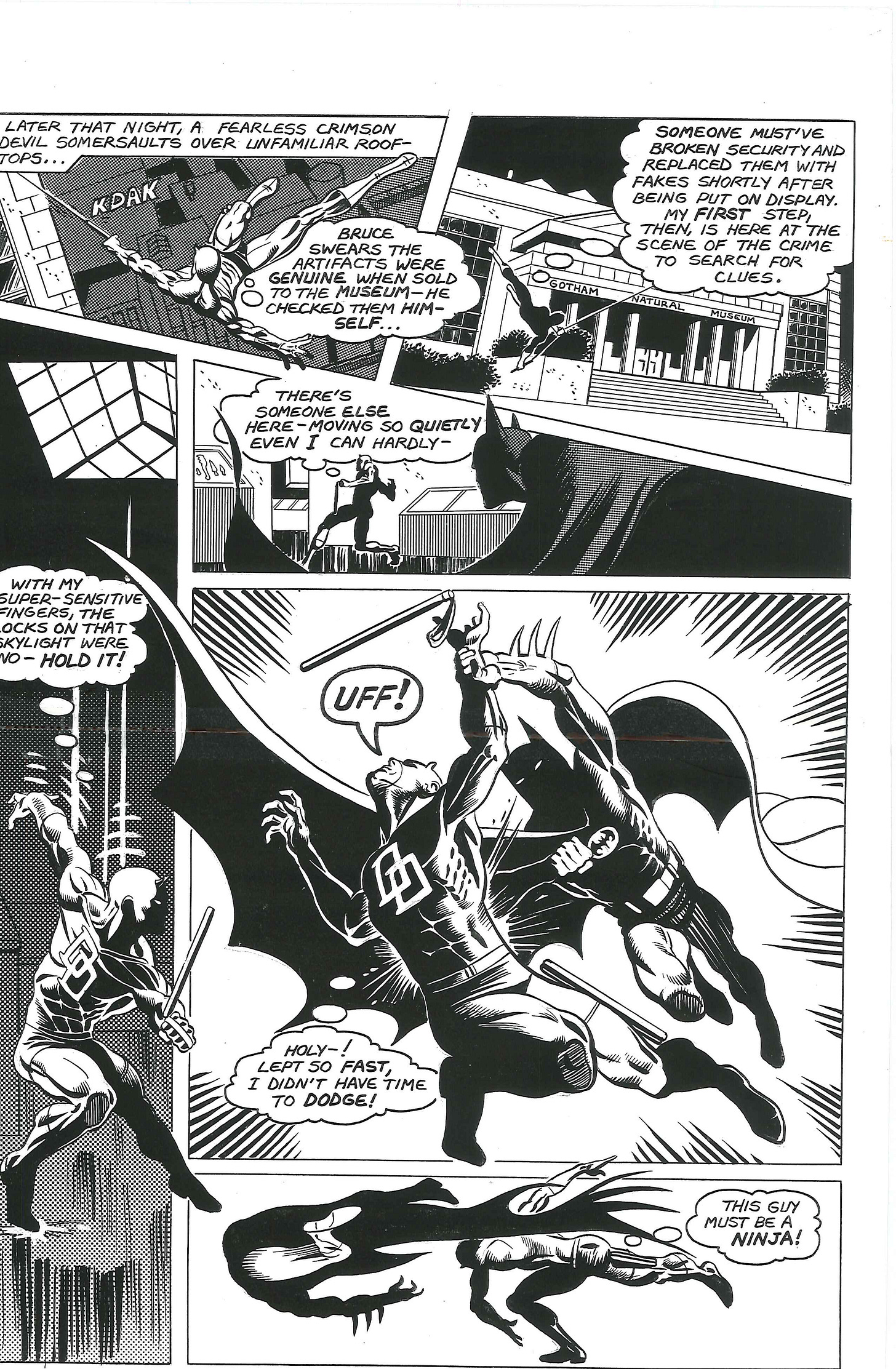

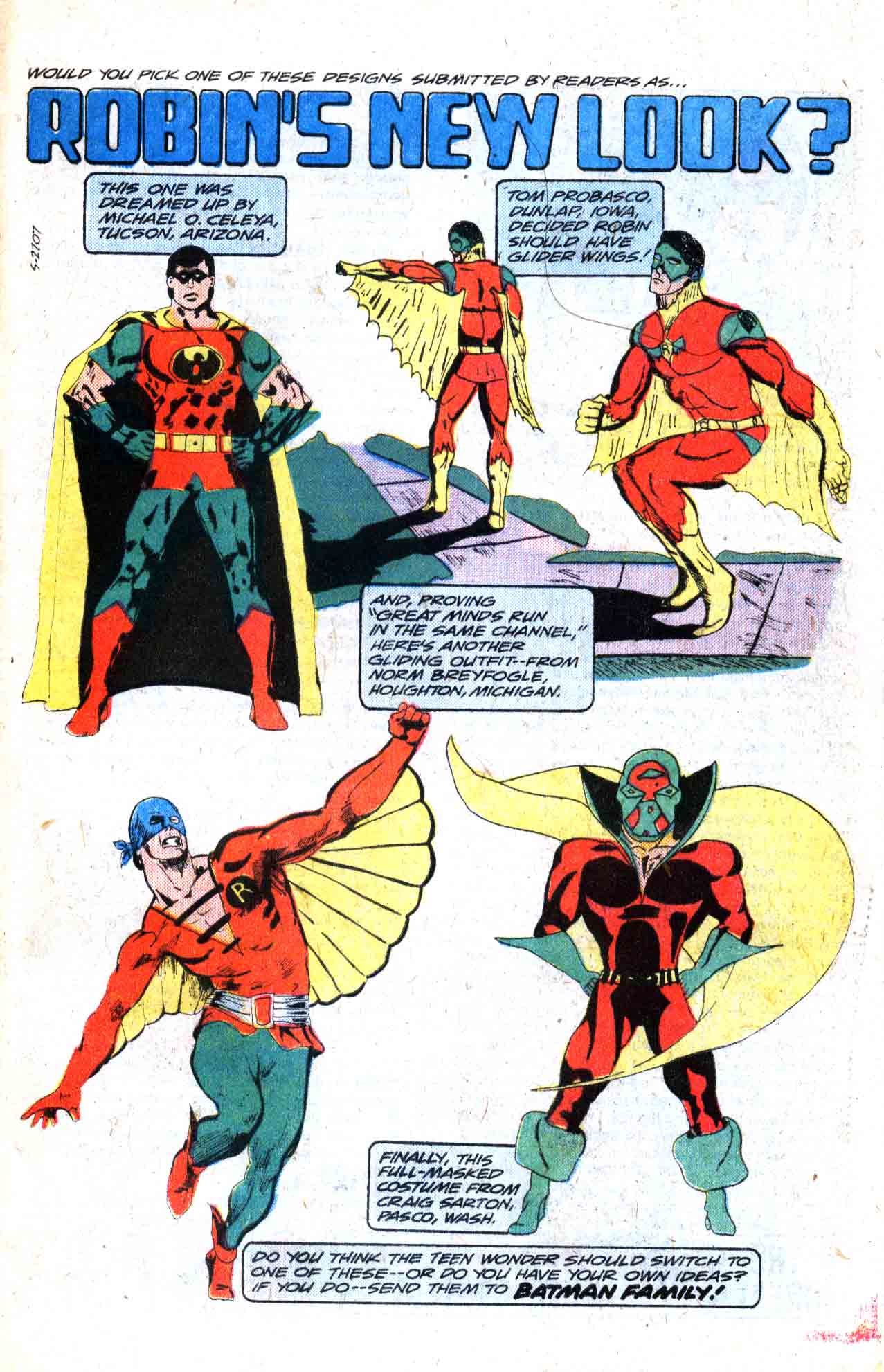

In the late 1970s DC Comics ran a competition for readers to design a new costume for Robin. As part of the competition readers submissions were published in an issue of Batman Family. Norm’s design, which wasn’t that far removed from the designs he would professionally submit to DC upon request over a decade later, was one of those selected to be published in Batman Family #13, resulting in Norm’s name and art being showcased by DC in a Batman title for the first time.

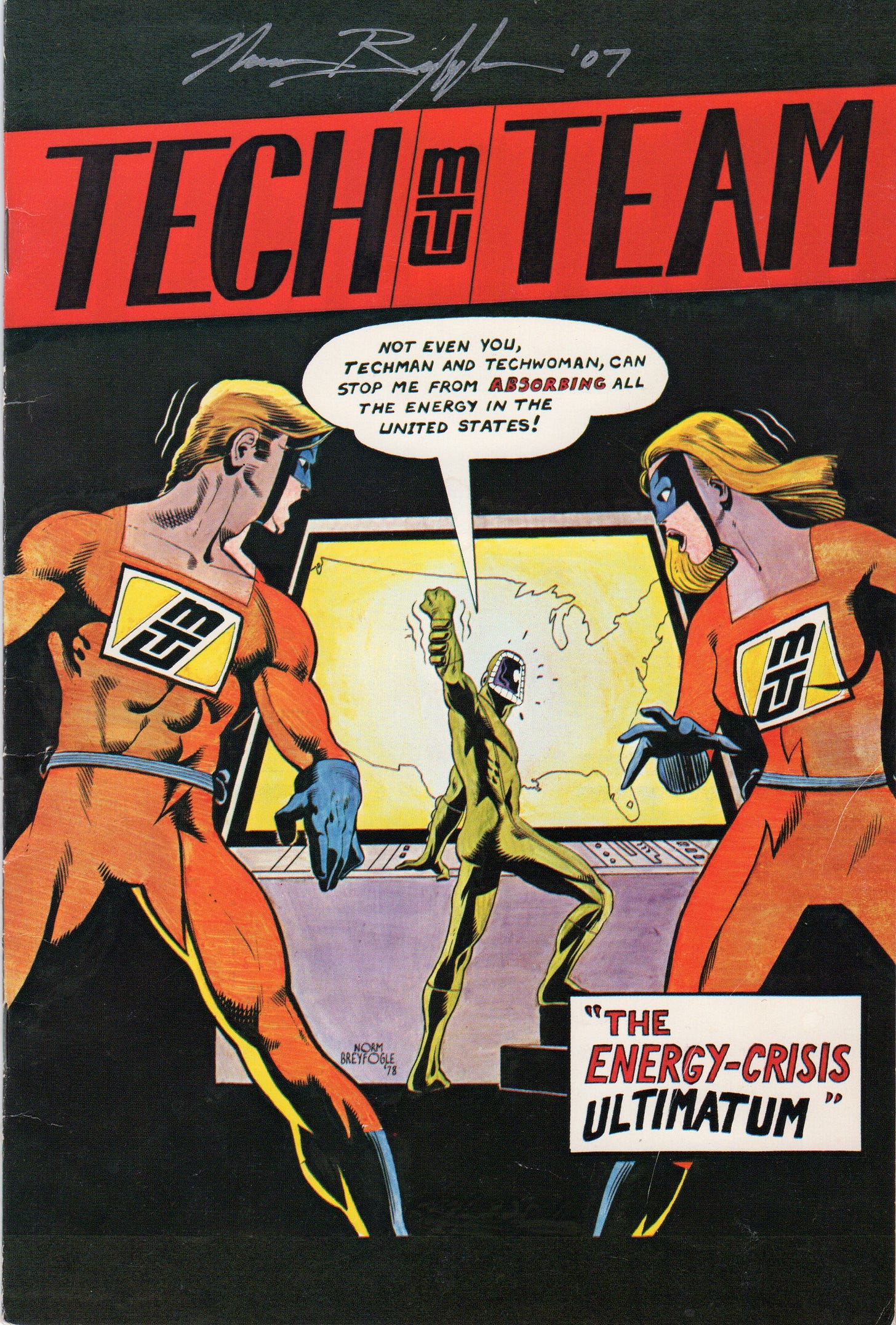

At the age of 17 Norm was asked to write and draw a full blown comic book, titled Tech Team for the College Of Michigan. The original art can still be seen at the college to this day and this led to Norm enrolling at Northern Michigan University where he majored in both painting and illustration. He fell one class short of graduation.

In 1982, Norm moved with his mother and brother, Kevin, to California. He found work doing technical design, including a stint with NASA where he helped with the space shuttle program by illustrating the official training manual for the refurbishment of the solid rocket booster. This led to more technical work for the Air Force.

While doing this technical work, he was sending samples to comic book companies, and, as is the way, he collected a number of rejection slips. A typical rejection came from Eclipse Comics, who told Norm that his penciling was weak but his inking was strong. First Comics replied to the same set of samples by telling him that his penciling was solid but his inking was weak. These contradictions both confused and amused him.

It was when he attended his first San Diego Comic Book Convention that things began to happen. He placed some of his paintings into the art show and came second. This led to an approach by art agent Mike Friedrich, who, via his Star*Reach imprint, was more than happy to sign the young artist to an exclusive contract. ‘Norm’s work was in the art show (at San Diego),’ said Friedrich, ‘Lee Marrs spotted it there and suggested that I take a look at it. I was impressed by his dynamic storytelling.’

‘I had a number of pieces in there,’ recalled Norm, ‘some black and white comics that had been unpublished, a Batman story and a couple of paintings. And one of them actually won second place behind Moebius’ first that year.’

San Diego also led to another opportunity. Norm was enlisted in Sal Amendola’s New Talent Showcase program, where his first professionally published work for DC was published, in issues #11 and #13.

Using his vast industry contacts Friedrich was able to secure Norm his first major comic book work drawing Bob Violence, then a back-up series in Howard Chaykin’s American Flagg (published by First Comics). Violence wasn’t a regular gig, stories were sometimes drawn by Joe Staton, but it did mark Norm’s breakthrough.

Bob Violence was a challenge for Norm. The art was cartoon like, which went against what Norm was wanting to do.

I’d never worked on anything as cartoony as Bob Violence. I’ve read about how Neal Adams had an early interest in cartoony art, exaggerated stuff, which really surprised me when I read it, so I didn’t think doing Bob Violence would affect my realism. I really got into that strip.[i]

Norm’s theory was simple – if it was good enough for Neal Adams, it was more than good enough for him.

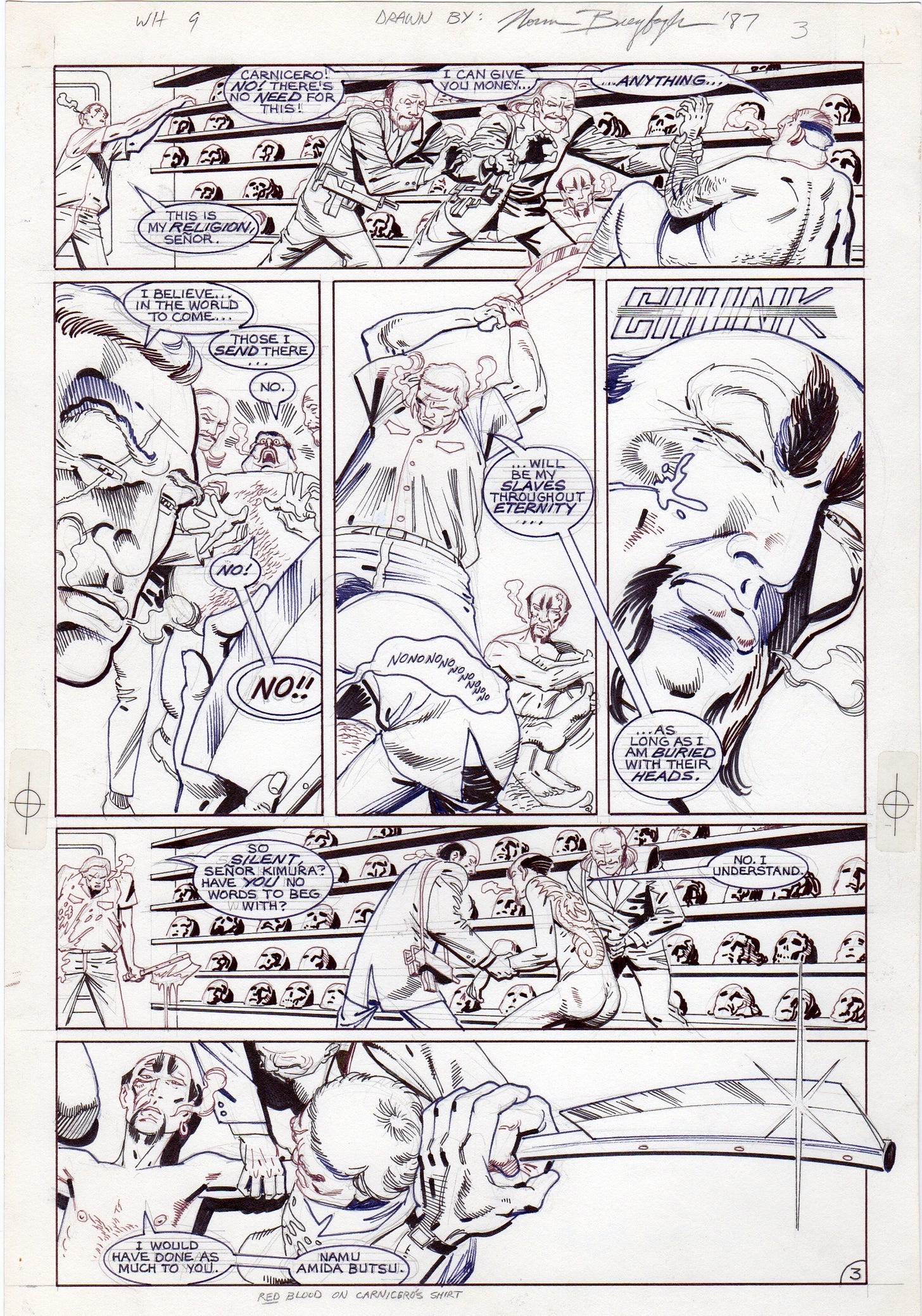

Norm’s work on Bob Violence didn’t escape notice and he was soon tapped to become an artist on First Comics’ Whisper, written by Steven Grant. Described by Norm at the time as being a ‘…political drama with a lot of sleaze.’ He started by penciling the third issue. By the seventh issue Norm was penciling, inking, lettering and hand painting the covers.

Painting was something that Norm loved to do. Inspired by old Gold Key comic books covers, he lobbied First Comics to allow him to paint. The first step was to send in color separations at his own expense, which led to the approval. The caveat was simple – even though painting took more time and work, First made it clear that the rate they’d pay for a painted cover was less than that of a line cover.

Norm wasn’t fazed. He wanted his paintings out there for two reasons. The first was he enjoyed the medium and was learning with each painting he completed. The second reason was to show other comic book companies what he was capable of. He would also state that he found painting the covers easier to do than penciling the interiors.

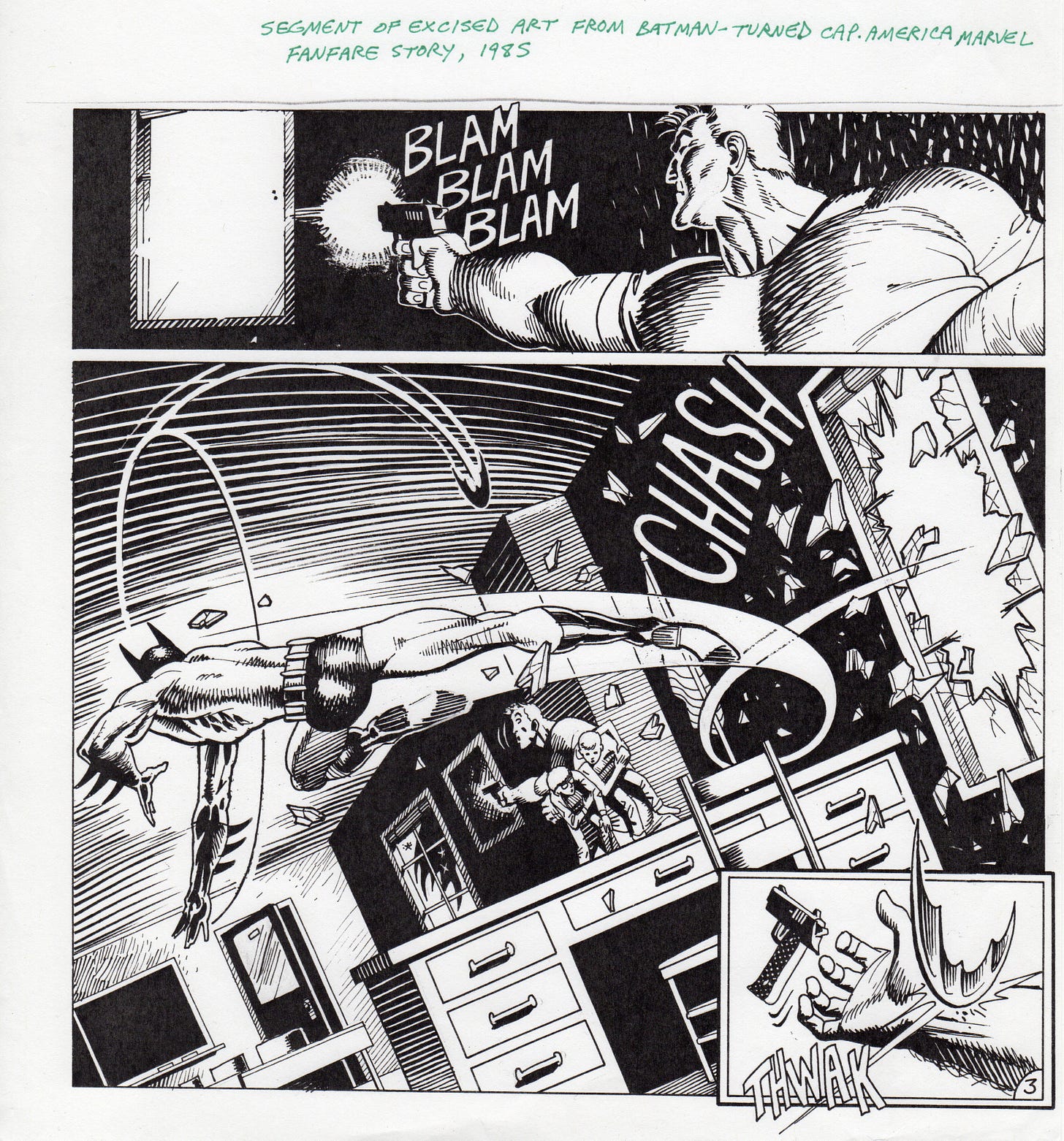

Norm had also managed to pencil a Legion of Superheroes back-up story and had sold Marvel a Captain America story, which he wrote, penciled, inked and lettered, which subsequently appeared in Marvel Fanfare. Marvel Fanfare was, at that stage, a title that showcased inventory stories, new talent and stories by creators who enjoyed a very flexible deadline.

The Captain America story began life as a Batman story. DC Comics rejected the story, so Norm merely cut the Batman images out, replaced them with freshly drawn Captain America figures and sold the end result to Marvel. Norm would later state that he threw all of the Batman illustrations in the bin shortly after.

‘The funny thing about that story was that DC didn't like the artwork, and didn't like Norm's work,’ Mike Friedrich said. ‘(so) Al Milgrom over at Marvel had Norm redraw the story as a Captain America story. Al said that after Norm's story ran, editor-in-chief Jim Shooter said, ‘This story was all wrong for Captain America - he acted like Batman.’’[ii]

‘As I understand it,’ said Norm years later, ‘when Shooter made that statement he didn't know the story's origin as a Batman story.’

Acting like Batman or not, this first work for Marvel was received with positive comments via the letters pages in Marvel Fanfare. ‘…I think that Mr. Breyfogle will be an artist to look out for in the future,’ wrote Kevin Hall, ‘his story-telling abilities are first rate.’ ‘The back-up feature was very good,’ wrote Alexander St Cloud, ‘Plotted, written, penciled, inked and lettered all by the same person? Wow!’[iii]

Norm also visited New York and made a pilgrimage to Continuity Studios where he hoped to meet Neal Adams. It wasn’t to be. As Norm told it.

Neal was ‘too busy’ to meet me, so he sent his daughter out because I was a nobody to Neal. She looked over my work and said she’d tell Neal all about it. I heard nothing. Later, when I was drawing Batman, Neal made contact and invited me to join Continuity. Now I was the one now turning Neal down.

Two issues after his Captain America story Norm was able to land another back-up feature into Marvel Fanfare, this time showcasing the Fantastic Four and drawn in a style very reminiscent of John Byrne and Jerry Ordway, both of whom were the current art team of Fantastic Four at the time.

Norm was being noticed.

Conversation with Norm

Norm: I’ve got the very first published comic that I ever did, the first comic book that I ever got published - Tech Team - which I’m sure you’ve heard about..

Daniel: You did that while you were still at school?

Norm: Yeah a friend of mine was I think a grade below me. He was a close neighbor of mine in my neighborhood.

He was familiar with my artwork because he saw it in school and high school and stuff and when I was about, well when I was 17 years old apparently he talked to his mother about it and she got the idea of putting together a promotional comic book for the local college and she was in the administration department at the college. I forget what her job was.

But her son, Chris Kipers was his name, he told me about that and she gave me a call and invited me over to their place to talk about this project. So we basically co-plotted it, she and I, and I don’t remember her name either except her last name Kipers. We co-plotted it and then I wrote it and drew it and well if you were to read it, it’s pretty atrocious. The artwork’s pretty well developed for a 17 year old, it’s relatively professional, pretty professional, and pretty darn good actually if I do say so myself, but the writing is just awful. You can even tell from the title, The Energy Crisis Ultimatum. It’s really corny. It’s like a Marvel, DC comic book from the 60’s.

Daniel: So what kind of art education did you have other than lessons at school?

Norm: Andrew Benson was a professional commercial artist that my mother took me to, drove me every Saturday morning for two hours to Carpentersville Illinois Saturday mornings, which I hated because Saturday was my day I didn’t have to get up for school, but I had to get up to go to these private art lessons. That was when I was 13 to 14 and up until that point I had only considered art as a hobby. I was really into it because I really enjoyed it but it was all just pure enjoyment and I guess I was thinking a little bit about my future but I was pretty young, I was thinking more about the sciences. I wanted to be an astronomer.

I remember reading The Search for Planet X which was about the 1940’s and I found that so fascinating and yet when I picked it up recently a couple of years ago, it was so boring I can’t believe I found it interesting at 13. But that was what I was into then.

Daniel: What sort of tools were you using when you first got into the comics? The Whisper pages I’ve got look like they’re inked with marker pen. Why marker pens as opposed to ink?

Norm: Up until that point, as an amateur, I had been developing my inking skills using brushes and dip pads and as I recall I was feeling like I had stalled with a brush somehow. I had stalled creatively like I had too much experience with it as an amateur and I felt using felt pens would force me to think of things in a different way and they really did. I think that’s the main reason I started using pens on Whisper. It wasn’t really because it was quicker, it wasn’t really that much quicker because like I said I’d developed my abilities with a brush. The main reason was because I could draw many small, thin, parallel, feathered lines, not even feathered but small thin parallel lines that I couldn’t do with a brush as well.

Daniel: So then what made you swap back over to ink?

Norm: God I don’t know. It’s too bad that I didn’t get Batman years later because I didn’t really switch back until well into Batman and it was just before DC stopped my inking stint, started getting inkers and wouldn’t allow me to ink my own work anymore.

And sometimes I’ve wondered if maybe it’s because I was using marker pens and I wasn’t using brushes or I wasn’t using permanent ink enough. I don’t see how they would normally care because they printed okay.

By the time I got onto Shadow of the Bat, I was using almost entirely permanent ink.

Daniel: Why brushes over pen?

Norm: Brushes are the most pleasant things to ink with because they’re such a smooth line. There’s no scratching, there’s so little friction felt at the tip. So that’s why I’ve always preferred to brush. But there are certain things that are really a lot more difficult to do with a brush than they are to do with a pen. If you want to do some of the Neal Adams type techniques and some of the modern image type techniques where there are a lot of thin parallel lines right next to each other and cross hatching. That’s harder to do with a brush. It’s not as pleasant to do with a brush.

There’s a tendency with a brush to draw you into a different style, well kind of an Alex Toth type style or a Nick Cardy style or a Joe Kubert style, all of whom are a bunch of my favorite artists. Sadly Nick’s style is not sought after by Marvel and DC anymore.

Daniel: You’ve also inked other artists along the way with different results. One that stands out on my mind is a Catwoman book you inked over Jim Balent.

Norm: That was weird, yeah that was very strange.

Daniel: How different is it for you to ink someone like that?

Norm: That was kind of painful. Although I did enjoy it because I always enjoy inking pencils I just knew that I was changing the character of the pencils so much that I didn’t think Jim would like it and I didn’t talk to Jim, I’ve never spoken to Jim. I pressed my editor at the time for what Jim thought about it, I don’t know who the editor was, but whoever it was seemed reluctant to give me any feedback. When I pressed the editor for Jim’s reaction basically he just said, ‘Jim didn’t like it’ and that’s what I expected.

My style was very different to Jim’s. Jim was going for a very Image Comic type style in a sense. It was extremely stylish, it wasn’t really naturalistic and I was adding a kind of naturalism to it. I tend to ink, when I ink people’s pencils I tend to impose my own style kind of like an Alfredo Alcala I guess or a Klaus Janson, and that doesn’t bother me personally except that if an editor doesn’t want that then yeah that bothers me in that sense but as a fan I would see combinations of inkers that would translate a penciller into their own kind of style. I always found that fascinating.

How do you think it compares to the previous issues?

Daniel: I’ve never been a huge fan of Jim Balent’s artwork.

Norm: Yep. Me neither.

Daniel: It’s so over the top and so unrealistic to the point where…

Norm: It’s plastic. A term that we would have used when I was in College for describing his style, one of the main terms would be highly mannered, it’s very mannered. It’s high on style and gloss and it’s kind of covering up a kind of lack of naturalism, a stiffness to the figures. That’s something that I tried to get around. In fact some of the faces, some of the figures I actually corrected technically from my point of view in terms of perspective and anatomy and I actually had to change one of them back because apparently Jim Balent was so dissatisfied that he complained and that bothered me because I’ve never had to do that before and frankly mine was better.

Daniel: When you ink a job yourself you generally draw thumbnails with pencils as opposed to the standard pencils and inks.

Norm: That’s right.

Daniel: Now some of these thumbnails like the first Spectre issue. Some of those are just gridlines with the globbiest shapes.

Norm: I know what you’re referring to. That was when I was still using my brother and he was enlarging my pencils and I wasn’t enlarging my thumbnail on a copy machine, he would just trace it full size. He was actually enlarging them by using a grid.[iv]

Daniel: How much work has Kevin done for you over the years that’s not been credited?

Norm: Oh quite a bit but that’s pretty common at the level of work that he was doing because he was basically just tracing my stuff. Now I’ve gone on my way to get him credit on some things especially where I felt that he was doing more than just tracing and I actually asked him to add a little more detail to the pencils.

I’ve never really sat down and figured out just how many issues it was or anything like that but for a good four or five years what I had him doing was using those gridlines to enlarge my thumbnails.

So basically what I got back was full size 11 x 17 versions of my thumbnails that he had enlarged by using a grid. Now it’s funny because he was doing that all along and there was no need. I don’t know why I didn’t think of it, it’s just crazy, I just don’t really understand it because I’m aware of copying machines, I use copy machines all the time, I never thought about enlarging them.

See what I do now, I enlarge my thumbnails on a light box to full size so nobody has to trace or redraw them at all and I can ink them right on a light box. I had an aversion to working on a light box because it didn’t feel natural.

Light coming through the paper, it just didn’t feel right and it took a bit of adjusting and getting used to and I’m pretty much adjusted to it, I have been for years. I got a lot of experience that way. So Kevin probably got a lot of layout experience that way that he wouldn’t have got if I had thought a little bit more and just not hired him at all and instead adopted my present technique a long time ago. So he really kind of lucked out. He got a good income for a while too especially for the amount of work he was doing. I was paying him a healthy percentage of what I was making. Kevin has gone on to do his own stuff. He has penciled and inked in his own right.

Daniel: Let’s talk paint.

Norm: I was finger-painting when I was in Kindergarten of course but I really started focusing on painting with those private art lessons when I was 13 or 14; and Andrew Benson, the commercial artist who was teaching me, originally got me started with pastels because he said they were easier to control and that was the way he taught his students about color. I never liked pastels because I hate my fingers being dried out. For some reason all my life I hate my fingers being dry, maybe because I don’t have workman’s hands because my hands are really soft. To this day, every day I put lotion on my hands, I’ve got soft baby hands, my girlfriends have always loved it.

But that’s why I hated pastels because they dry. Chalk basically is what it is. It’s kind of a pastel with a little bit of grease or oil in it so it’s not as quite as dry as chalk, but it’s basically chalk and I hated working with them because it got my fingers really dry and also there’s a lot of friction when it hits the paper, kind of like with using a pen as opposed to a brush. I like the liquidity.

So I couldn’t wait to get past the pastels and then we did and I started using oil paint, I just fell in love with it immediately. So I was doing oil paintings all the way through high school before I even went to College. When I was a born again Christian for four years in high school almost all my paintings were religious in nature. Basically all of them were. I did paintings that depicted the salvation of man, the fall of man, the Garden of Eden, Jesus battling Satan, blah-blah-blah, went on and on and on, and they were in oil on canvas before I even went to College; and that’s something that really bothers me sometimes when I think about it. I get a real thirst for doing some oil paintings again because I haven’t done any because of time constraints because they take forever to dry. I haven’t done any for… God I haven’t done an oil painting in, could be 20 years now; and it’s the best kind of painting, because it’s the smoothest, you get the richest depth of color and gradation and it’s the most permanent.

Daniel: It’s clear that you use reference when the painting calls for it.

Norm: I very rarely used any photo reference from our watercolors. They were usually a live model. Most of the watercolors that are in that sketchbook are done from live models in class. What were you going to ask about the photos?

Daniel: You’re not doing a straight copy of the photos, you’re painting from the photo, and you’re not copying the photo onto the page, if that makes sense. You’re not tracing it?

Norm: No I didn’t trace it, that’s true. With a watercolor it really wouldn’t make much difference. First of all it would be hard to trace it literally because the watercolor paper’s too thick. I guess you could possibly trace a watercolor on a light box but I’ve never even tried that. But a watercolor is so temperamental that it wouldn’t, it’s not really ideal for tracing. I guess I could have traced the figure on the watercolor paper with pencil and then water colored it, added the color afterwards, but it just seems too laborious.

I’ve done very little tracing at all. I’ve always felt very little reason for tracing. Even when I was a kid, when I was drawing Neal Adams covers I didn’t even think about tracing them. It’s funny; I’ve heard that other artists or other kids were doing that. It didn’t even enter my mind. It was like, well anybody can trace. A monkey could trace it if you could train it to do it. It’s just following a line. I wanted to learn to draw from the very beginning.

So I was drawing Neal Adams covers when I was eight years old. They were crap of course but I was trying.

Daniel: One of your paintings that leaps out at me is the cover art for the first issue of Metaphysique.

Norm: That’s mixed media. Its rotering art of colors which I was using a lot back then, in fact I painted all of Batman versus the Demon: Origin Of Ras A’Ghul with mixed media but mostly rotering artists colors and it’s basically a waterproof watercolor. I really miss those because they don’t make those anymore. So now I have to use Doctor Martin’s dyes and the quality is different. I guess maybe I can adjust to them but I just don’t think they’re as good. So I really miss those rotering artists colors; and then on top of that I layered, I added layers of color. You can do that with these waterproof watercolors because unlike watercolor where you have to get the density down pretty much immediately because if you try to add a color afterwards it changes the quality of the surface of the paint because it’s not waterproof. With rotering artists colors and waterproof watercolors that doesn’t happen.

Once it dries you can paint over it and the underlying layers remain the way they were.

So you can build layers and you can give the illusion of like the depth of the oil painting or an acrylic painting. Waterproof watercolors are transparent, but once I built up a lot of those layers then I would go over the painting with some opaque colors with acrylic or even a… well no I never used oil because it takes too long to dry. The only reason I switched from oil was because oil takes too long to dry and I really miss working in oil. All of the full color paintings I did for Detective Comics, the few that I did were done in the same way.

Daniel: Going back to Metaphysique, the first version, I don’t know if you remember it or not?

Norm: Right, yeah. Now that was done in acrylic, not in rotoring artists colors, it wasn’t a buildup of… it was before I even tried using waterproof watercolors and I didn’t want to do it just in watercolor, I wanted to use permanent… I wanted to use something that you can add layers, add layers to without disturbing the layers underneath, so it had to be waterproof.

So I was using acrylic. At that point I was doing a lot of acrylic painting. Those two covers were done with almost entirely in acrylic paint and they were among the first fully acrylic paintings I had worked on. I had just began doing that when I was in college mainly because, well again, because of the time constraints.

I wanted to learn to do it because I knew they would dry faster and I would be able to handle them better, more quickly. Send them to publishers or get them scanned or whatever but yeah those were among the first, well that was probably within the first year or two that I was working with acrylics when I did those covers.

Daniel: Were you using those painting techniques with the watercolors and the acrylics for interior pages that you did?

Norm: That’s a good question. There’s a lot of mixed media in the interior pages. The first story in the first issue, The Path, isn’t full color. I started it in oil. The first panel was done in oil, the first panel on the first page was a problem, so I switched over to acrylic and the rest of the book, the rest of that story was in acrylic, but it was all full color. I expected it to be printed in full color but during the process of printing it, the Eclipse Comics decided to print the entire book in black and white, without telling me and I was a little bit upset by that when I finally saw it. They didn’t even tell me until it was in print. It was like, ‘Wait a second, how come this isn’t in color’. The original pages of The Path are really pretty, they’re full size; they’re rich in color, much prettier than you see in black and white.

Daniel: It was a weird book because I’m looking at stories such as The Path and Microwars which is almost like a Bill Sienkiewicz style. There are just so many art styles in that book.

Norm: Yeah well I was experimenting a lot. There’s not much more to say about it than that. I hadn’t yet had a… when I did those stories that was; actually they were done before I did Batman even though they weren’t published until afterwards. Most of those stories, all of those stories, except… well not all of them.

The second issue there were a couple of stories that I had written earlier and I redid later after I have had… after I had cut my chops, I’m doing monthly comics. But most of the stuff in the first issues, I think, were all done back when I was ‘an amateur’ before I was drawing Whisper even, before I drew Bob Violence; and some of them were even done while I was in college. So I was experimenting a lot with different styles and I hadn’t really developed any kind of formula for turning things out on a regular basis, on a swift periodic basis.

You know I actually considered becoming a trucker.

Daniel: Good God why?

Norm: Well because I wasn’t breaking into comics and I was… it was one of my first years on the California Coast after I’d finished my college years and we were living out there and I was looking for work. I worked in McDonalds for all of four hours. Luckily I didn’t have to continue there because I got my first drafting job. But before that I painted houses, I delivered telephone books. Back when I was delivering these telephone books, I had to walk all day long up and down these neighborhoods and I was still recovering from a broken heel bone. I was off the crutches and I wasn’t in a cast anymore but my foot was still quite tender and God I was limping badly by the end of that day.

I was a draftsman at a power plant. It paid the bills. It wasn’t fired up at the time. I wasn’t running a radiation risk. This was before Diablo Canyon started. They were having all kinds of problems with the nuclear regulatory people and other protest groups because they’d built the plant too close to the San Andreas Fault. I used to go into rooms and see so many conduits and pipes which were being installed as back-up systems in case of an earthquake. They were putting so many conduits in these rooms that you’d walk into one of them and just see solid pipe. You’d have to wriggle and crawl and climb over things in order to get into spots where you’d have to make a drawing. It was fun. I got to do lots of chin ups on the pipes. And there were times when I was out in the field away from the drawing board. Got to walk around. I miss all that. But it was still too technical for me. It doesn’t compare to free-hand drawing.

Daniel: Batman, Birth of The Demon was totally painted, from the covers to all the interiors. How daunting was that and how fast can you now paint?

Norm: Birth of the Demon was indeed a huge challenge for me. Over one hundred pages of full-color illustrations was a massive undertaking by any standards, and I highly refined my illustration skills while doing that book. At the beginning of the book I was taking three to four days to finish a single page, but by the end of the book I was actually doing one page per day! And many of the techniques I employed on that job I still use in my illustration work today.

Daniel: How do you look at the changes of your art?

Norm: When I first started drawing Whisper and Bob Violence it was just a matter of getting the stuff done and trying to have a sense of quality and I didn’t really have the formula yet. So I was developing my style so to speak and it was all under pressure.

Once I was getting proficient at it after a couple of years and I was finally drawing Batman, I was always feeling like I’ve got to strive to do something radically different here, like I was doing back when I was in college. Like you said there were big differences in styles between the black and white work in Metaphysique and the painted color work in the second Metaphysique. I felt that I needed to get to challenging myself, which is the main reason I switched from using a brush to markers on Whisper as well because I thought it would help me break up my style. I didn’t want to get stuck in a rut; and so I felt the same way when I was… after I got proficient with meeting the deadlines, I felt like okay now I want to start challenging myself again but I never really got around to it.

In fact what slowly happened was I segued into my own style and ever since then, even to this day, it’s become more a question of perfecting that style and it’s not like I sit, it’s not that I consider it a rut anymore, it’s more like… it’s more like it’s my own expression, and it’s a question of perfecting it.

Daniel: So how far do you think you can go with it?

Norm: Well to be brutally honest with myself I have to say that I have taken it as far as I really can. I can always perfect it, I can always get it, make it smoother, I can always get it more efficient, I can always get more economical with my line, I can become more like Alex Toth. In fact by the way Thad Branco likes to compare me to Alex Toth, which I find very flattering.

If I want to get away from that, if I want to get away from a formula, I feel like the best way to do it is by writing and yet I don’t have any, I don’t have any comfort at all in making a living off that. That’s what I’ve said recently is that when I write I feel like I used to feel when I was sitting down at a blank page and drawing.

Drawing now is really comfortable and I really enjoy it and I get a real kick out of designing a page in a way that the storytelling is smooth, that it’s dynamic, that it has all of the elements that I want all juggled together in a perfect balance and that’s what I love about comics now and I don’t feel like I’m in a rut because that’s how I approach each page; and yet there’s a certain lack of impressionist to it. There’s a certain lack of… well each page is a challenge but I guess… I don’t know. I’m trying to get at what you’re question was and the point that you raise and really what it comes down to is when I’m writing I feel the most like I’m free again. Like I don’t, like I’m not dealing with a style. I don’t feel like I have a style in my right. I’ve sensed a certain development of a style with like my poetry but it’s not very much there yet. So I feel a lot more freedom. I guess that’s what it comes down to, I feel like there has been more freedom. I don’t know.

This kind of stuff I don’t really think that much about. When I approach a job, I approach a job and I do it to the best of my abilities. I’m not like, it’s not like I’m really trying to change what I’m doing. But I guess if the right job came along and I was asked to do it, I could do that. That’s the way I would do it. The best way of changing my style in the past was to change the tool that I was using. Like for instance, if I were to do a fully painted story now, it’s been a long time and that would be a real blast.

Daniel: Let’s divert for a while and talk about your writing. I think you’re actually quite a good writer. The stuff that I’ve seen you write has been very impressive.

Norm: Thanks. I really appreciate that.

Daniel: You have genuine talent. You can write poetry, and I’m always envious of people who can write poetry.

Norm: Some of my poems are good. Poetry is a very elitist skill and I would assume that among really good poets I would be considered pretty lame. But maybe even among really good poets some of my poetry, I tend to think that some of my poetry maybe I can find at least a couple of them that some really good poets might think were worthwhile. When it comes to my short stories I think my short stories are even better frankly. But that’s just me.

I won’t go so far as to say that I’m a Haiku Poet, Haikuist, what’s the term?

Daniel: I’m not sure.

Norm: It’s the latter of Haiku. I think I’ve done enough of them now to be considered experienced. I was going to say expert but I don’t know what that takes, in comparison to Siacarcu, who supposedly wrote 24,000 of them in one day and one night I’m a pleb.

Daniel: But it’s unbelievable that he could physically write that many of them in one day and one night.

Norm: Oh the Encyclopedia Britannica wouldn’t lie to us.

He didn’t even write them down, he just recorded them, so probably most of them were probably crap and a large percentage of them probably weren’t even proper Haiku’s.

Daniel: You could probably say 24,000 but physically writing them I think that would be…

Norm: It sounds impossible. I actually figured it out once. I forget exactly what the figures were because I forget exactly how many, I think it was 24,000, I forget exactly how long it took him supposedly. But it came down to just a few seconds per haiku which means he was just talking constantly.

With my Haiku’s I actually labored over them for five months. I was writing these back and forth, Denis Janke has got his own 1,300 Haiku’s and even more than him from what I was able to gather. I have gone over mine and tried to improve them but there’s so many of them that I think it would be an almost endless process. Because every time I go back to those and I read them I find little ways to improve each Haiku. But I’ve really labored over them and unlike Siacarcu who just rattled them off and nobody even recorded them. Maybe I would be qualified as a Haiku expert.

How many do you have to write to be an expert?

Daniel: I don’t think it comes down to mere numbers. Jim Steranko is considered to be an expert in comic book art and he didn’t draw that many comic books.

Norm: Well that’s true, that’s true.

Daniel: And it’s a case of …

Norm: Quality not the quantity.

Daniel: Now with the revision thing, going back and changing it, how much of your art would you go back and change?

Norm: Oh very little, very little.

Daniel: Say I came up to you and said, ‘I want you to…’

Norm: Oh you mean if I could.

Daniel: If you could.

Norm: Like what Neal Adams did in the recent collection of his Batman material?

Daniel: Bang! If I’m going to go and put out a collection of Whisper and say to you, ‘Okay, I want you on board with it’, how much of that would you change?

Norm: If I started making changes it would be endless. So I would probably not make any changes. Well I can’t say that. That’s off the top of my head. My first reaction is I would not make any changes. But if it was a reality and I was given the chance to change it and I was going to be paid for the time that I put in to changing it, I would probably make some changes. I would only have to guess but off the top of my head I don’t know.

The more I think about it, I’ve thought about this before, not with Whisper but about Batman collections especially after Neal Adams starting changing his Batman collection, I started thinking about that and we even discussed it on my message board and I think I’ve concluded that it’s probably better to not touch it at all and the best example I have of that is Neal Adams.

The things that he changed most of them were for the worst and the things that were for the better were the lettering. Like sound effects were re-lettered. The coloring was arguably better too. But the actual drawing changes that he did I felt like the originals were for the most part much better.

Daniel: It is funny because Alan Kupperberg summed it up perfectly for me which was, ‘I hated him doing it because there was nothing wrong with it in the first place, why change perfection’.

Norm: I wouldn’t feel that way about my own work and that’s exactly what Neal Adams didn’t feel either. But learning from Neal Adams example, I think that would prevent me from following my inclination to want to change it because I don’t think it would be a good idea.

First of all there’s a good argument from principle against it, why change the past, it’s kind of sacrosanct; and if you start changing it, my main problem would be if I started changing, Neal Adams must have faced this too. If you start changing something where do you stop? I could redraw the whole damn thing and it would be better but I can’t, I don’t have the time or the energy to do that and then it wouldn’t be a reprint anyway.

Daniel: Exactly. Revisioning it or not revisioning it, re-imaging it.

Norm: Yeah a revision, it would be a revision in the total sense which you never see, almost never.

It would be really interesting to know if Adams since then has felt differently. How often has he looked at the stuff? Will he get distance from the stuff and look at it and go, God the originals were better.

The most difficult thing about these questions, these issues, is the element of subjectivity. There’s no way to really remove it. When I was looking at this stuff, the Neal Adams Batman collection, I was doing my damnedest to try and like it. I guess with the computer terms it would be like a worm virus. I was trying to worm out all of the old patterns of recognition that I had for the old stuff and try to look at it fresh, just as freshly as I’m looking at his new stuff and it’s impossible to do.

When I look at the original printing, the original inking of his old Batman stuff, I can’t separate that from the time in which I saw it and the way it’s impacted me emotionally and it’s got a certain aura about it that it wouldn’t have if I saw it fresh for the first time now. So actually the best way to determine these things, whether or not it was a good move on his part or not, whether or not his changes were better would be to get people who had never seen the original in print or at all ever, and then they would just compare them side by side. That would be really interesting to do.

I pride myself on my objectivity about things like this and it seems pretty damn blatantly obvious to me that most of the changes weren’t as good as the original. The originals were inked by Dick Giordano, or most of them were inked by Dick Giordano, and Dick was frankly a better inker in a lot of ways than Neal. Although in some cases there are some issues of Neal Adams Batman that I value because Neal Adams inked them.

Do you remember Moon of the Wolf? I think that might have been inked by Neal Adams, I’m not sure. The Five Way Revenge, I’m pretty sure that was inked by Neal Adams too.

Daniel: The shot of the Joker running on the beach.

Norm: Right. God that shot has become the ultimate Batman pose for years and decades now. He even put it on the cover of one of the Batman reprints and it wasn’t as good as the original.

Daniel: Now I wonder whether or not when he drew that he thought ‘this is the icon shot’. Have you ever drawn something and thought that this is going to be the poster pin-up or this is going to be the money shot, without it being a splash page or the cover?

Norm: That’s a big question. I guess the general answer is yes, but the way you phrase it I would have to say not really because you can’t predict what’s going to have lasting impact, not really. You can guess that certain covers, like first issue covers of a new series, might have an impact.

For instance the first issue of Prime, I felt the importance of that first issue but of course Prime has disappeared. It’s like Prime never existed.

I put a lot of effort into that first issue where he’s holding his finger up in a number one sign and got the big smile on his face, showing off his muscles. I felt it was an important issue and of course the number one issue cover is an important issue for the series. But to your general question I guess the ideal is to develop your abilities to the point where you wouldn’t be ashamed to have anything have lasting impact, and that’s the value of refining your style.

For instance Alex Toth, again a good example. If you can pick anything that he did in his later years, any panel or even in his earlier years for that matter because he was such a master but especially in his later years, you can pick any panel and it’s majestic in itself. It can stand the test of time. It’s not like some things are better than others, it’s all great and that’s the ideal.

Daniel: Look at Batman #457 where you introduced the new Robin.

Norm: Right, the double page spread.

Daniel: You must have known that was going to be picked up?

Norm: I was working under such pressures and I had so much going on in my life and I guess I knew that to a certain degree but I still don’t to this day know just what kind of lasting value or how important it really is. I get a certain inkling of certain people, certain people it is but time marches on. If you look at the top editors at DC now, they seem to think that I might as well just be Alex Saviuk.

Which isn’t fair to Alex by the way.

Daniel: It’s a very fair call.

Norm: Well that’s one thing I don’t want to be. I don’t want to be a hack (not that I’m saying Alex is a hack). I don’t want to be a hack, I’ve never wanted to be a hack, because I love drawing, I love comics; I love the medium of comics. I want to have the impact that my favorite comics had on me when I was a kid; and that’s actually some of the most gratifying experiences I’ve had is when fans relate to me that they did get that impact from me.

Daniel: In a way you’re on a double edged sword because the fact that DC haven’t hired you to come back and do Batman means that you’re not in competition with yourself. Everyone looks back at those runs of Detective of Batman and Shadow of the Bat and go, ‘It’s great’. You never got bad. You never went downhill.

Norm: Well I would have to get a cross-section of opinion; that’s a high opinion.

Daniel: You know what I mean though. If you look at say when John Byrne went back into that X-Men stuff, people were saying, ‘Yeah it’s not as good as it once was’ and there was a little bit of luster lost.

Norm: No that does bring up something else. I’ve wondered if I were to do a Batman, very recently especially because I thought that we had Alan Grant and I had a project, a Batman project, that DC was going to okay. I thought it was already a done deal. It did enter my mind a number of times that no matter how good I do this, no matter how much I think it’s better than my earlier work, a lot of the fans that see it are going to be comparing it to their golden age experience of seeing my earlier work and they just might not think it’s as good even if it’s better, objectively if that means anything.

Objectivity, is there any objectivity in art? I’ve had some of the most interesting conversations with artist friends about that, the idea that there is an objective sense of quality. It’s the same question that comes to morality or any kind of refined experience or attitude or outlook or point of view. As soon as you get away from the consensus, there’s no objective way to measure objectivity. All you’ve got is your own feelings.

Daniel: And you did say that whole nostalgic thing. To use the classic example, when I think of John Byrne and Superman when he relaunched it, I loved it. I really did. Then I looked at what he did when he went back to the character in the Generations mini-series, it looked half finished.

Norm: My prime example for this would be Jim Aparo. Jim Aparo is good just to illustrate both points. The change of his quality of its work from the early 70’s to before he died, both illustrates a certain amount of objectivity about taste, about the quality of the drawing, but recently I’ve looked at a lot of his earlier work that I thought was fantastic and I see all kinds of problems with it that I didn’t see it at the time.

It’s a really darn good question. Is there any objective quality to two dimensional imagery, after all it’s just ink on paper.

Objectively speaking, it is ink molecules on pulp wood bark. Every sense of quality that we give, one example of that over another example is so wrapped up in the complex moronal structure of our own experiences there’s arguably no objectivity to it at all. When you look at different work from your own experience, you can’t help but feel that there’s an objective sense of quality there.

Daniel: But what’s good to one person is no good to another.

Norm: Exactly.

Daniel: I know people that will sit there and tell me that Alan Weiss is no good.

Norm: Really? There are people that say Alan Weiss is no good? You visit mental institutions often? I guess it all comes down to…

Daniel: …how we view it.

Norm: So there’s certain objectivity. But even the objectivity itself is an illusion and you don’t even see that until you can escape it.

On a different topic, some of the horror stories I’ve heard in the comic industry have made me realize that I’ve been extraordinarily lucky. Maybe it’s because I started working for DC really early on. I didn’t work for a lot of independents before I became famous because of the Batman stuff. Maybe that’s kind of protected me.

Daniel: You worked for both DC and Marvel at the start of your career. So it’s not like any small publisher is going to be able to say to you ‘Oh look you’re breaking in and we do this thing here and this is how it works: you pay us and we’ll put it out there for you’.

Norm: I would have been that stupid early on. I remember in some of my early letters to DC when I was sending them samples. I was telling them like many wannabes were, I’ll work for free. You hear this all the time from amateurs that want to break into the industry and I was saying the same thing and I’m just lucky that nobody took advantage of me.

I wouldn’t do that now. If somebody wants me to work for free, that’s something I’ve avoided. Even when everything was falling apart and DC and Marvel weren’t hiring me and I couldn’t find any work, I was getting offers but they were basically Image Comics type offers which I would have done if I had some money in the bank and I didn’t have a lot of debt but it just didn’t make rational sense to me. I think my rationality saved me to a certain degree. I was more willing to become a bartender or to work as a janitor than to do our work for free. It didn’t make any sense to me. I needed to make an income.

DC wouldn’t accept work for free anyway. It has something to do with their professionalism. Maybe it’s because they’re a big fish in a little pond and they don’t want to disturb their position but they regularly refuse work for free.

[i] Amazing Heroes #174, March 1989

[ii] Prime Suspect by Rogers Cadenhead

[iii] Marvel Fanfare #33, July 1987

[iv] Kevin Breyfogle. An artist in his own right, Kevin has worked with Norm since Norm began working at DC drawing Batman. Typically Norm would do the initial layouts and pencils, Kevin would enlarge them and tighten the art and Norm would then ink the finished result. Kevin would often be credited with ‘Art Assists’ on a lot of Norm’s books.

Next: The Majors: 1987 – 1993. Including conversations with Norm, Alan Grant and Steve Mitchell, plus contributions from Denny O’Neill, Jose-Luis Garcia-Lopez, Tim Sale and Mike Friedrich.

Thanks so much for publishing this!! Norm’s voice comes through so clearly. I don’t pretend to have known him as well as you did, but I really loved his work, and deeply enjoyed the times I got to talk with him at length. Getting to read this account means a great deal to me.