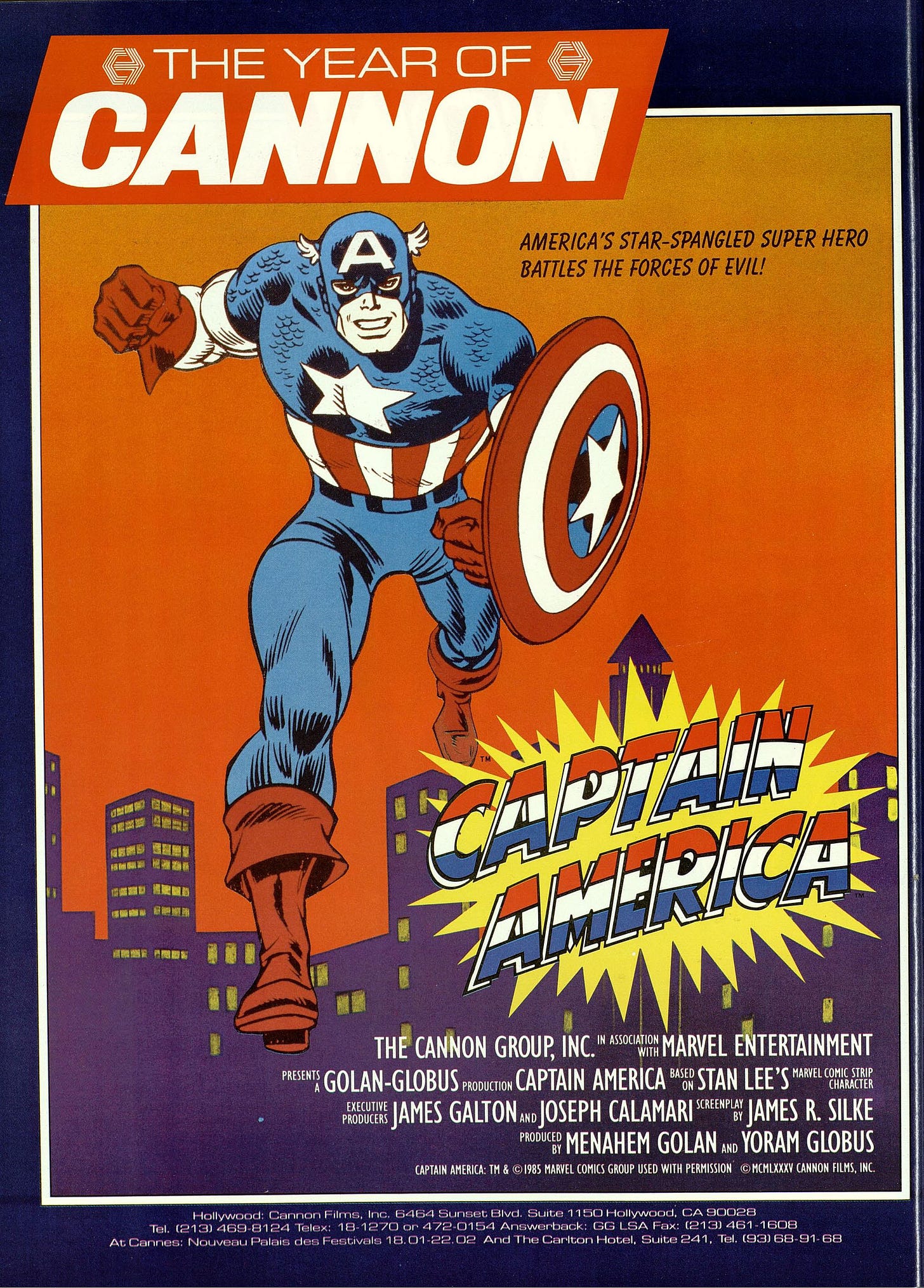

Captain America: Making Movies With Stan, Joe, Jack in the 1990s.

Superheroes in Hollywood. An on-going series of articles looking at the various superhero films pre-2000

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Daniel Best - Author to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.