It all started on 5 July 1928. That’s the date when Philip Francis Nowlan published a novella titled Armageddon 2419AD in the pages of Amazing Stories Volume 3, Number 5. Even though the magazine is dated August 1928, copyrights and indicia of the magazine quickly show that each issue was published on the fifth day of the preceding month.

Nowlan’s novella, a science fiction story, was a first person account by a World War One veteran named Anthony Rogers. Rogers was born in 1898 and went into suspended animation in 1927 after being exposed to radioactive gas in a mine. He wakes up in the year 2419 and finds America at war. He joins the battle, meets a woman named Wilma Deering and the rest just follows. At no point in the novella is Rogers referred to as ‘Buck’, nor does Anthony leave Earth, two factors that would follow in the strip to come, at least at first.

At the time of publication, Nowlan was earning a living writing a series titled His First Job, which was syndicated by King Features Syndicate. He had begun the series in 1927. Previously he had worked in the Editorial Department of the Retail Public Ledger in Philadelphia and penned other series, Your Names History and First Jobs of Big Men, again, both for King Features. All told, Nowlan had been writing for newspapers since 1919. On the personal front, he married Teresa Junker the year before, on 6 June 1918.

Shortly after publication of Amazing Stories, Nowlan was approached by the John F. Dillie Company to work up a science fiction newspaper strip based on his novella, which Dillie would offer to newspapers for syndication via his company, National Newspaper Service.

John Flint Dille was born into a world of literature. His father, Jesse Brooks Dille, founded Dixon College, Illinois, in 1881, three years before John Dille was born. Dille’s mother, and wife of Jesse Brooks, Florence Flint Dille, was the daughter of the college’s first president, John C. Flint. Jesse Brooks Dille would serve as college president for thirty years. Much of John F. Dille’s early life was spent on the college and he was highly educated. After finishing his education, Dille set out to work at a number of jobs, eventually finding himself working for George M. Adams, the founder of the Adams Newspaper Service in Chicago. In 1916, he founded the National Newspaper Service and began to oversee the syndication of cartoons, text and strips for American newspapers.

One of the people who supplied Dille with material was artist, and former World War 1 pilot, Lieutenant Richard Calkins. Dick Calkins, as he preferred to be known, began his professional career after the war, and was cranking out one panel gags for various newspapers before landing a steady job illustrating and writing a gag strip titled Amateur Etiquette: Politeness for Beginners for John F. Dille. He started that strip in 1925 and was working on it until 1928. When the concept for Buck Rogers was worked up, Calkins was reported as pitching an idea to Dille for a newspaper strip based on cavemen and prehistoric monsters, ala The Lost World.

(Above: the cover for Amazing Stories, August 1929. Despite what many people have thought, the cover image is not Buck Rogers. The image illustrates E.E. Smith’s Skylark)

Who approached who with the idea for a newspaper strip? Depending on whose story you chose to believe, shortly after publication of Armageddon 2419¸ either Nowlan approached Dille with an idea for a newspaper strip, or Dille tapped Nowlan for the same.

It is important to note that, right from the start, Armageddon 1419 was never registered for copyright protection. The issue of Amazing Stories was registered for copyright on 16 July 1928, but that was for the magazine itself, not for the contents, other than editorial content. Thus Armageddon 2419 was in the public domain from the moment it appeared. No copyright notice appeared on the story. It is also worth noting that the cover for the issue in question does not feature Buck Rogers, instead it is an illustration for the main story in the issue, E.E. Smith’s The Skylark of Space.

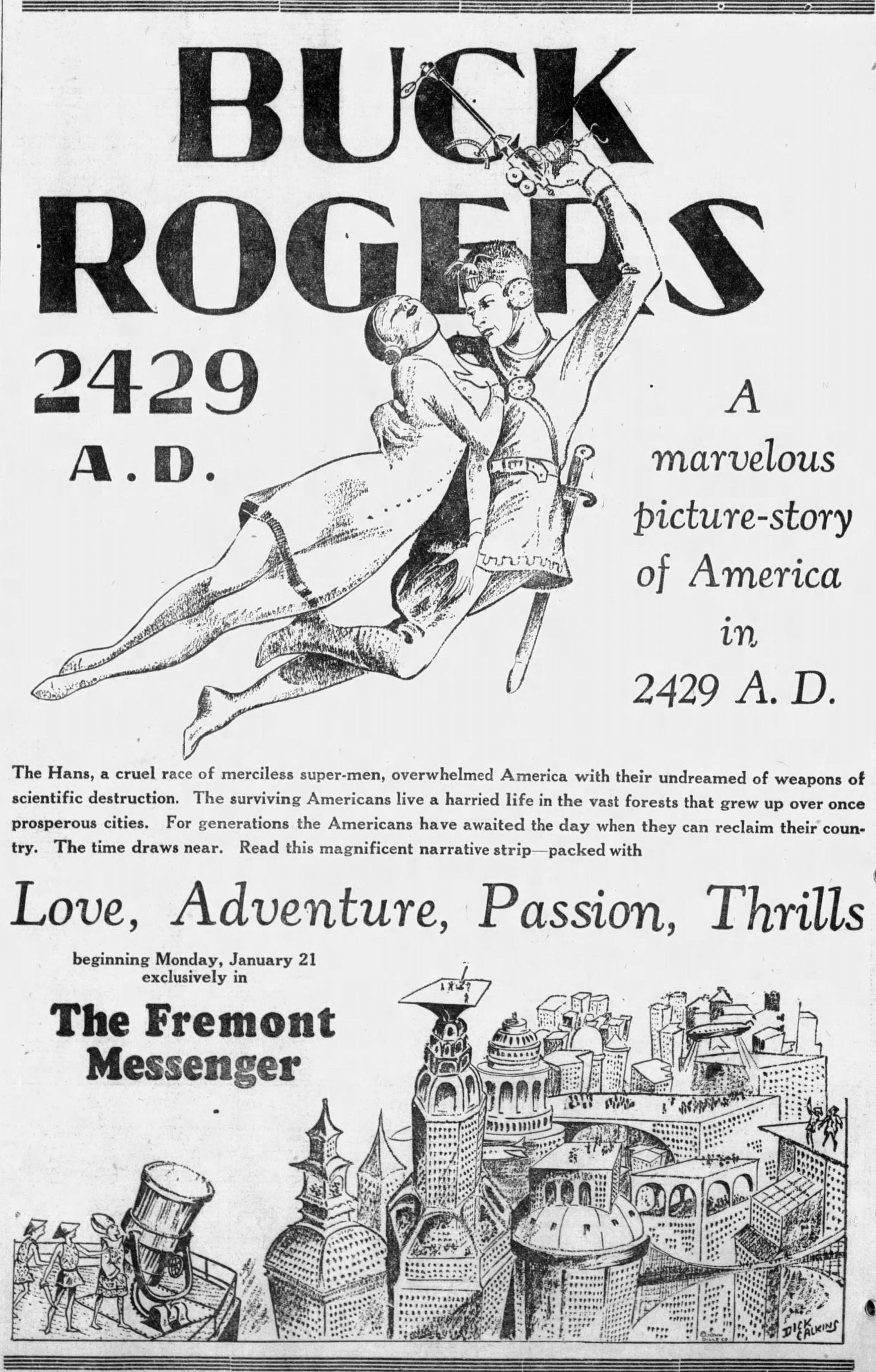

No matter who approached who, the first contract between Dille and Nowlan was executed and signed on 27 August 1928. The contract calls for Nowlan to be paid 25% of gross sales, with a guaranteed $50 per week for the first five weeks, and $75 per week for every week following.

Working from his basic idea, Nowlan took Armageddon 2419, renamed the hero Buck Rogers and he submitted his first copy for the Buck Rogers newspaper strip to Dille on 13 September 1928. Dille then engaged the services of Dick Calkins to illustrate after rejecting Calkins own cavemen strip.

It couldn’t have been that simple. In 2020, Flint Dille, the grandson of John F. Dille, would challenge the narrative that Nowlan created Buck Rogers.

“Armageddon 2419” was a Rip Van Winkle story about a guy named Anthony Rogers who fell asleep in 2019 and woke up five hundred years later. It was set on Earth and involved various techno-tribal organizations rising up against their Han overlords in America. It had ray guns and backpacks, but what’s most significant is what wasn’t there. Buck Rogers has been known as a space hero, but Anthony Rogers never leaves Earth. There are no space ships, no bubble helmets, no Warlords of Mars, Venusians, or anything else space related.

Somewhere in the transition from short story to comic strip, Anthony Rogers became Buck Rogers. There are various theories on where the name “Buck” came from. Some say he was named for my grandfather’s dog.

I developed a theory about what was my grandfather’s. It is utterly scientifically indefensible, but the ways in which brains work are partially genetic—I think. There were certain ideas, inventions that seemed like something I’d think of. Just unique fingerprinty things. I guessed those were my grandfather’s. By all accounts, my grandfather (JFD) was hands-on. Nowlan would die in 1939 of cirrhosis of the liver. My grandfather had hired Phillip Francis Nowlan to write it, but Nowlan missed deadlines and couldn’t quite wrap his head around it.[i]

Nowlan would not die of cirrhosis of the liver in 1939, but we will get to that.

Jim Steranko, writing in the first volume of his History of Comics, offered this account.

The idea for a comic strip that portrayed the world and the worlds of the future was conceived by John Flint Dille, president of the National Newspaper Syndicate. Impressed by the science fiction pulps of the day, Dille envisioned their potential in a series of continuities. He contacted pulp writer Philip Nowlan who adapted his highly romantized (sic) tales from the pages of Amazing Stories into strip form. Loosely based on Armageddon 2419 A.D. Nowlan’s script had the hero, a World War I pilot, become the victim of a 500-year state of suspended animation. He awakes in 2430 to discover the Red Mongols have conquered America. At Dille’s suggestion, Nowlan had changed the hero’s name from Anthony Rogers to Buck Rogers.[ii]

Steranko went on to claim science fiction writer E.E. Smith’s Skylark and Lensman series ‘blueprinted every Buck Rogers character and situation to follow.’ The first installment of Skaylark appeared in the same issue of Amazing Stories as Armageddon 2419 A.D. and Lensman didn’t appear until 1948. While an argument could be made for Skylark influencing the overall feel of the Buck Rogers newspaper strip, it is difficult to understand how the series Lensman could have influenced Buck Rogers when the latter had been in print for two decades prior to the former’s publication.

One person who felt that Buck Rogers wasn’t an original idea was author Violet Snir. Writing under the pseudonym of Berenice V. Dell, Snir had published a book titled The Silent Voice in 1925. Described as a ‘highly racist, sexist novel set in 4000 A.D. in which a land run by women and non-Aryans is at war with the exiled Aryans[iii],’ Snir felt that similarities between her novel and Armageddon 2419/Buck Rogers were enough to file a plagiarism suit against Nowlan claiming $1,000,000 in damages in 1935. The suit went nowhere, but it would be the first time that a court case would be filed with Buck Rogers.

No matter who did what, it is entirely possible that Nowlan and Dille collaborated on the idea to get to the final point, much the same as Bill Finger fleshed out Bob Kane’s Batman idea.

Buck Rogers was the first in a genre of ordinary men being cast into a futuristic world and left to fend for themselves. Strips and stories in a similar vein would follow Buck Rogers. Some, such as Flash Gordon, would eclipse it. Others, like Brick Bradford, Don Dixon, Speed Spaulding and Dan Dare would fade into obscurity. The strip also influenced the likes of George Lucas (Star Wars) and Gene Roddenberry (Star Trek). No matter the success of those who followed, Buck Rogers holds the distinction of the first.

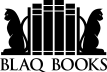

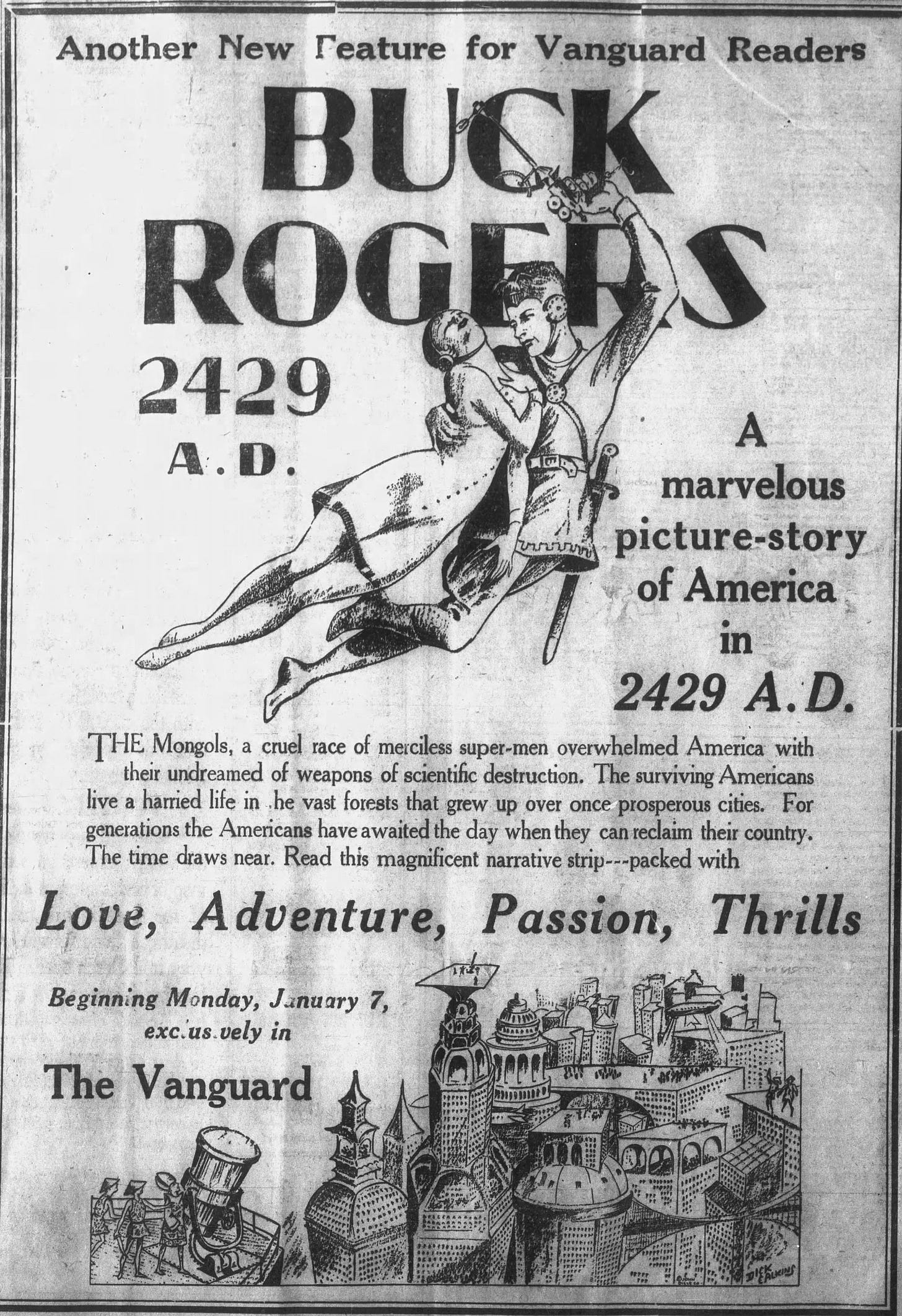

On the second of January 1929, ads began to appear in newspapers for the Buck Rogers strip. The first strip proper appeared on Monday 7 January 1929 and began to appear in other newspapers from there, with several starting its run two days later on Wednesday, 9 January. Another newspaper strip debuted the same day in the form of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan by Hal Foster.

In the beginning, Dick Calkins would draw the daily strip; Russell Keaton would handle the Sunday strips. On the strength of his Buck Rogers work, Keaton would be approached by Jerry Siegel in 1933 who felt he’d be able to sell his Superman concept as a newspaper strip easier with an artist of Keaton’s caliber as opposed to Joe Shuster. Artists who drew the strip over its life included Murphy Anderson (better known for his later Superman work), Rick Yager, George Tuska and Zack Mosley (Smilin’ Jack). When the strip was resurrected in 1979, Gray Morrow was tapped to be the artist, followed by Jack Sparling. It becomes very clear that the character has attracted some of the best the genre has to offer – even Neal Adams had a small stint on the strip, and Frank Frazetta provided cover art for the 1950s comic book adaptations.

On 5 February 1929, Nowlan published another novella. Titled The Airlords of Han, the story is the direct sequel to Armageddon 2419 A.D. This story was also published in Amazing Stories and also was not registered for copyright.

On 29 July 1929, John F. Dille, via his National Newspaper Services, filed the first trademark registration for Buck Rogers. The trademark was for an ‘Adventure Strip for Newspapers’ and Dille made the claim that the name had been use since 10 September 1928. This gives the first major clue as to when the name was actually thought up.

On 9 September, using the pen name Frank Phillips, Nowlan’s story, Onslaught From Venus was published in Science Fiction Stories.

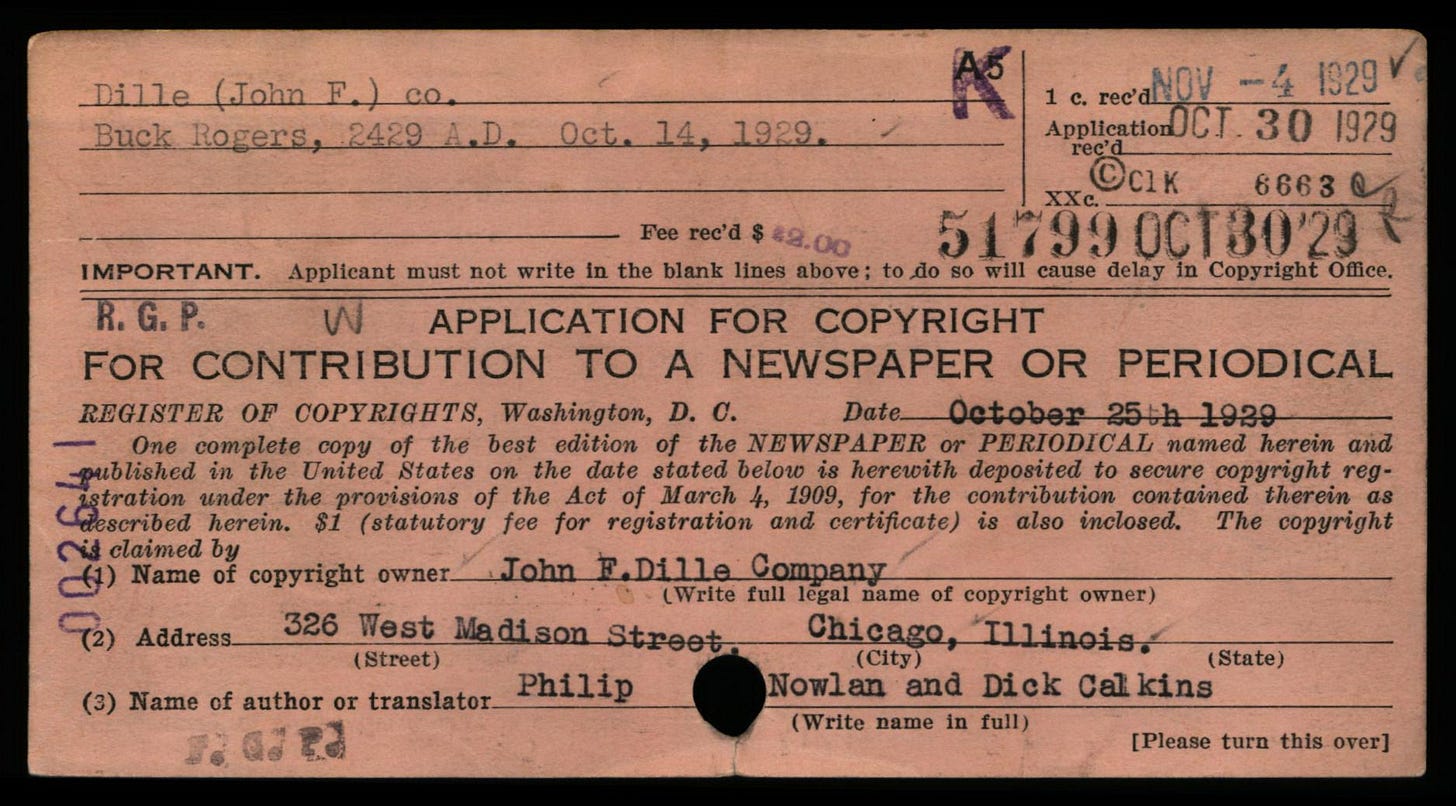

Dille filed the first copyright application for Buck Rogers on 4 November 1929. Dille claimed ownership, with Nowlan and Calkins listed as the authors. The copyright application was to protect strips 1 to 204 of Buck Rogers 2429 A.D. At no point was the strip listed as a work for hire creation. Dille would be sure to lodge copyright applications each year for the newspaper strip.

On 15 November the deal between Dille and Nowlan was reworked. This new Memorandum of Agreement was for Nowlan to write the Buck Rogers newspaper strip, now titled Buck Rogers 2429 A.D.. The Memorandum calls for Nowlan not to sign his name to any other strip for the life of the contract without the prior permission of the Syndicate. His pay is increased and is now 25% of the gross after the Syndicate subtracts $300 per week for costs. If total sales do not reach $20,000 per year, the Syndicate will increase the profit cut until that amount is reached.

Finishing off 1929, on 24 December, National Newspaper Service was granted the trademark for Buck Rogers. It was clear that, at this stage, John F. Dille was the rightful owner of the trademark and copyrights to the series.

Dille would often be referred to as the creator of Buck Rogers, as would Nowlan and even Calkins. It wasn’t out of the ordinary for a publisher to be credited as a creator. Even though Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Superman, editors Mort Weisinger and Harry Donefeld both claimed to be the true creator of Superman, more than once, and these claims made the media.

Next: Dille tightens his grip on Buck Rogers. Films, television, radio and more.

[i] Dille, Flint. The Gamesmaster: My Life in the '80s Geek Culture Trenches with G.I. Joe, Dungeons & Dragons, and The Transformers (2020)

[ii] Steranko, James. The Steranko History of Comics Volume 1 (1970)

[iii] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/12584570-the-silent-voice

Delightful. I wish you'd do something similar for Tom Corbett, Space Cadet.