The Buck Rogers newspaper strip continued to gain traction and popularity as the 1930s rolled on. Plans were afoot to capitalize on the growing popularity by exploiting it outside of the confines of a syndicated strip. The strip evolved, and Buck was no longer confined to planet Earth, but was now moving into the realms of traditional science fiction, with rockets, space travel and ray guns. Proof of the popularity came when The Wichita Beacon reported how an eleven year old, Tom Hargiss, designed a space ship for Buck Rogers to leave Earth. Once he finished the design, he then mailed it to Calkins. The design was highly complicated and well thought out.

In the beginning, each year of the strip was set exactly 500 years in the future. In 1929, the strip was titled Buck Rogers, 2429 A.D., in 1930, Buck Rogers, 2430 A.D. and so on, until the strip was retitled Buck Rogers In The 25th Century as of October 1932. In 1933, the strip was carried with both titles, 25th Century and Buck Rogers, 2433 A.D. From 1934, the 25th Century title was put in place forever.

Calkins was now illustrating the syndicated strip Sky Roads, as written by Lester J. Maitland. Sky Roads was an aviation themed strip, which would also evolve over time. Often the two strips appeared next to each other in the newspapers.

On 2 September 1932, National Newspapers Service and Nowlan signed a Memorandum of Agreement to sell the rights for a radio show titled Buck Rogers 2419. The price was to be a minimum of $250 per week for a minimum of thirteen weeks. If the final price was more than $250 per week, Nowlan would be paid 50%, otherwise he was to receive 30% of the gross. The radio show debuted on 7 November 1932. By 1935, it would be heard across America.

Each year Dille would register the copyrights for each series of stories as they appeared in the newspapers. Each year they were registered as belonging to the John F. Dille Company, authored by Phil Nowlan and Dick Calkins. This would remain until well into the 1940s, even after Nowlan’s untimely death.

Dille was also careful to register his trademarks. Toys, rocket ships, toy pistols on 11 April 1934. From then on it was free for all for Dille. Toy wagons, baseballs, helmets, candy, clothing – even explosives. Dille registered for the trademark for it all. All told Dille registered eleven trademarks between July 1929 to July 1960, with six separate registrations coming on 27 August 1935 alone. Most of these trademarks now lie expired.

Behind the scenes, all wasn’t rosy with the strip. William Randolph Hearst approached Dille in late 1933 and offered to buy Buck Rogers. Not to be deterred by Dille’s refusal, Hearst hired artist Alex Raymond to create his own spaceman adventure strip. Titled Flash Gordon, it wasn’t to be the last time someone stole the basic idea of Buck Rogers and ran with it. Over time, Flash Gordon would overtake Buck Rogers in the public eye, mainly due to Hearst being the only owner of the strip, via his King Features Syndicate. As with all things Kings Features, Hearst and his successors made sure they rarely went out of print, and, if they did, it wasn’t for long.

It also helped that Raymond was a far superior artist to Calkins.

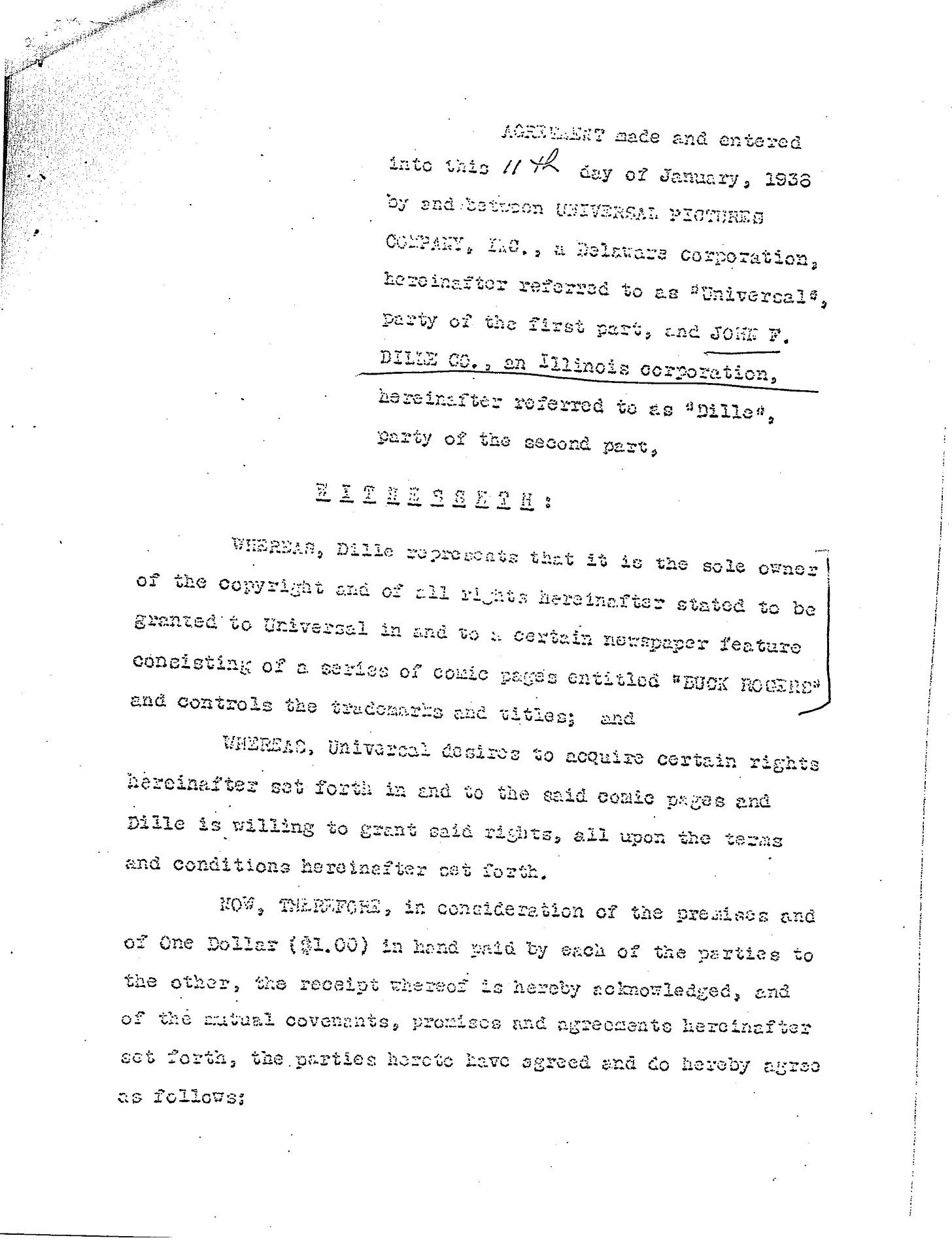

On 11 January 1936, Dille signed an agreement to allow Universal Pictures to create a Buck Rogers serial. Flash Gordon had beat Rogers to the screen, and there was no reason to believe that Rogers couldn’t do the same good business as Gordon did.

The deal was for a twelve part serial. The serial starred Larry ‘Buster’ Crabbe, making Crabbe one of the few people to play both Flash and Buck.

Crabbe wasn’t the only similarity between the two serials. The same director was used (Ford Beebe) along with the same music (which, to be fair, was recycled from Universal horror films such as Bride of Frankenstein and Were Wolf of London and many of the same sets and locations. Later in life Crabbe would comment that there was no real difference between the two serials and that he often got them mixed up with each other.

The strip was still motoring along, albeit with changes. In 1939, Nowlan was off the strip as writer, but his name would remain. As to if he was fired, or quit, the mystery remains. Artist Dick Calkins would take over the writing from Nowlan and leave most of the art to his assistants. Interviewed decades after the event by the Comics Feature, Murphy Anderson, who took over the art duties on the strip from Calkins, claimed Nowlan was fired from the strip for ‘being too far out there’ with his storylines. Anderson would also recall that he was paid $65 a week for drawing the daily strip.[1] It was said Dille had promised him royalties but never delivered.

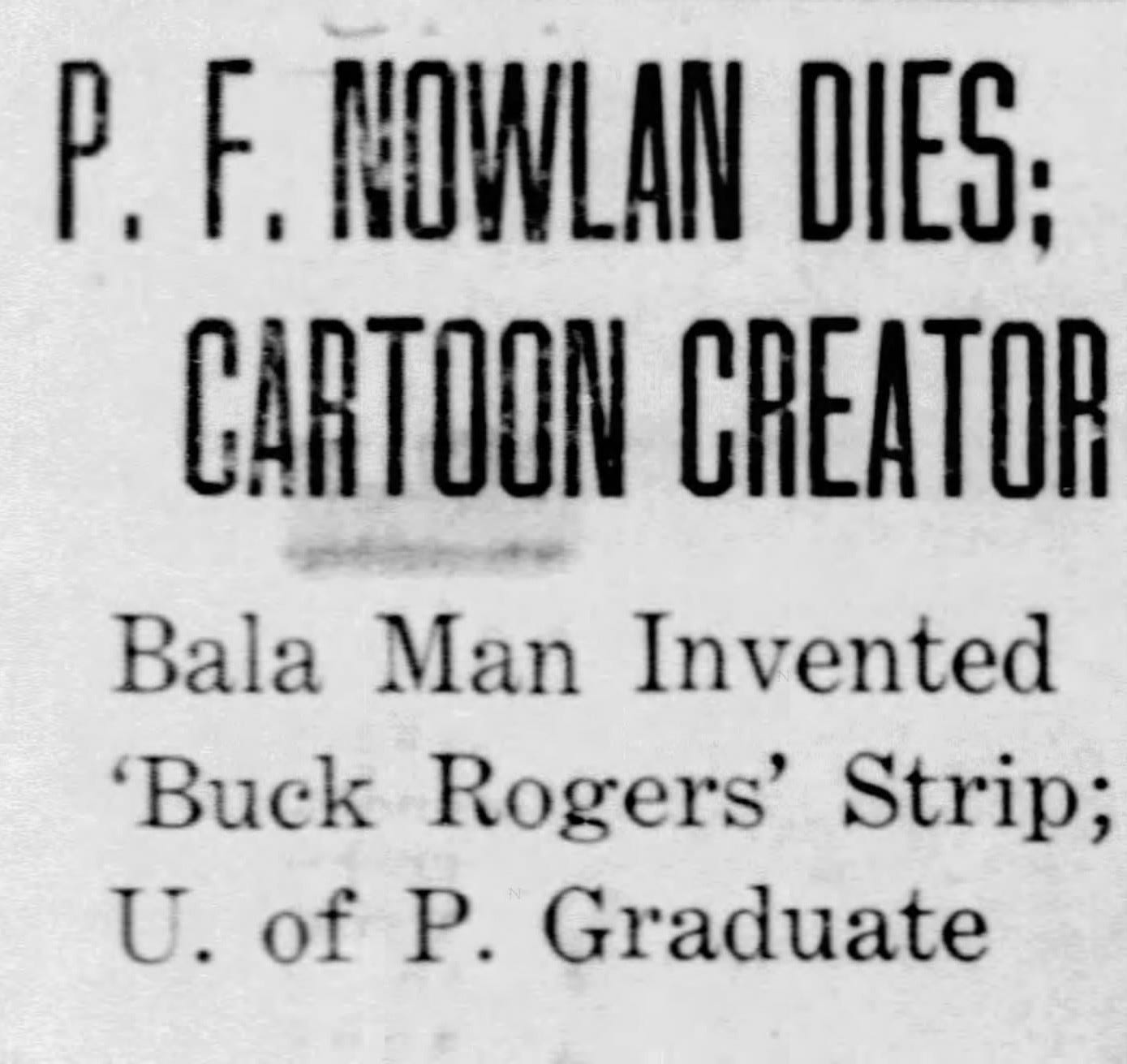

Sadness hit when, on 1 February 1940, Philip F. Nowlan died, aged 52. He didn’t die of cirrhosis of the liver in 1939 as Flint Dille claimed, instead he suffered a stroke two weeks previously. His obituary states that he had been in poor health for the previous two years, which might have been have factored into Flint Dille’s story. Nowlan left a widow, Theresa and ten children, Theresa[2], Helen, Louise, Philip Jr, Michael, Mary, Lawrence, Patrick, Joseph and John. Shortly after his death, fantastic Adventures published his story The Prince of Mars Returns. Astounding Science Fiction would publish his last story, Space Guards, in May of the same year.

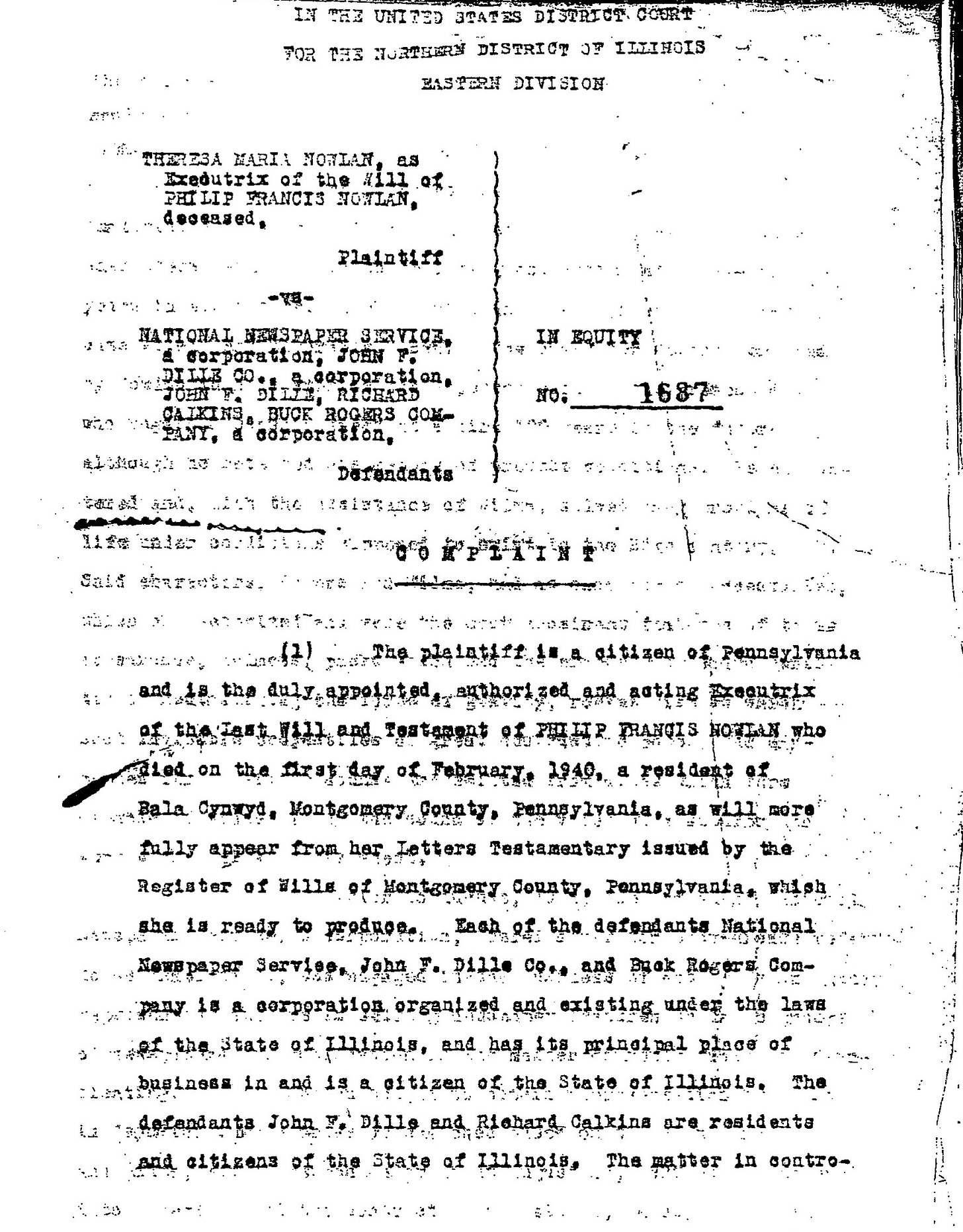

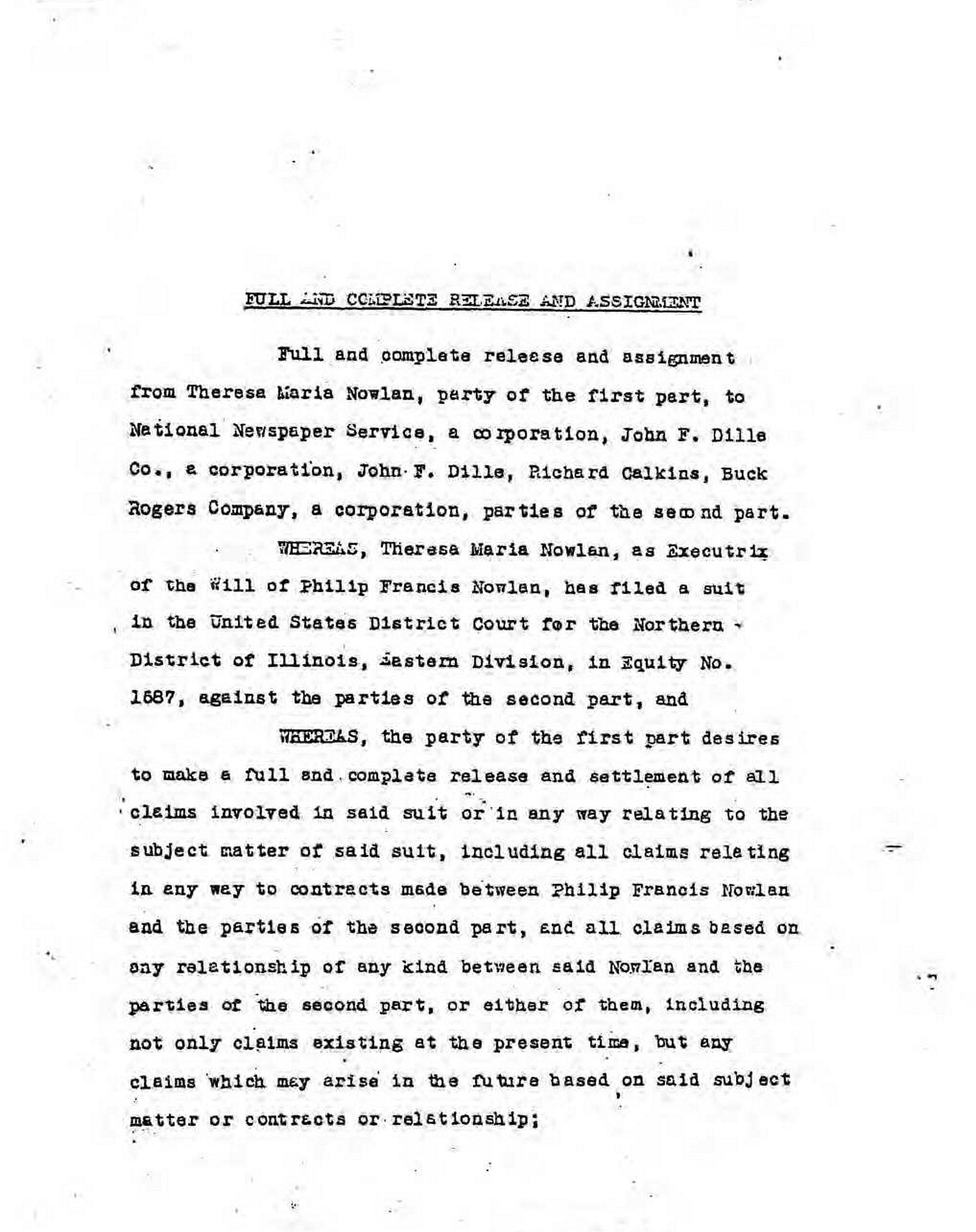

Payments of the strip appear to have stopped upon Nowlan’s death, so Theresa Nowlan filed a suit against National Newspapers for the rights to Buck Rogers, which Philip Nowlan had bequeathed to her in his will. After some back and forth, Dille settled with Theresa Nowlan on 14 April 1942. An agreement was drawn up and executed by Theresa Nowlan. This release and assignment between Dille, Nowlan and his estate, released and assigned all Nowlan’s rights in Buck Rogers to Dille, Calkins and the Buck Rogers Company for the sum of $1,750. The assignment covered everything but, notably, did not mention the original novella, Armageddon 2419. The assignment would see the 1941 court case dismissed without costs.

From that date onwards, Buck Rogers legally belonged to John Dille and the National Newspaper Syndicate, Inc. The Syndicate was run by John Dille until his death in 1957, after which time it was taken over by his son, Robert. Robert died in 1983; the Syndicate was wound up in 1984.

In November 1947, Dick Calkins stepped away from the Buck Rogers strip for good. His replacements were John F. Dille as writer, and Leonard Dworkins on art duties. This lends credence to the theory that Dille did collaborate with Nowlan in the early stages of Buck Rogers creation.

The growth of television in the late 1940s and early 1950s saw programmers looking far and wide for content. Dille signed a deal to get Buck Rogers on television for 1950. Sponsored by Peter Paul Candy Manufacturing,[3] the show would be live action. The Maxon agency had put the deal together and shopped it around, CBS-TV passed on Buck Rogers and elected to pick up Dick Tracy. NBC-TV also passed on Rogers.

Earl Hammond and Eva Marie Saint were both offered five year deals to star as Buck and Wilma. Saints contract called for her to do the show for $125 per week, with yearly raises of $25 per week. Her contract was worded as to prevent her from appearing on radio or television, nor to promote a show that wasn’t the sponsors, for the duration of the show. Hammond was promised a thirty nine week minimum at $200 per week, with his pay increases to hit $700 in the fifth year. That was if the show aired for eight consecutive weeks. Both could be sacked with five days’ notice if the sponsor withdrew from the show. Earl Hammond took the offer, Saint passed. Eva Marie Saint didn’t suffer. She moved from television to stage and then finally cinema where her career went from strength to strength, winning an Academy Award in 1955 for On The Waterfront. On 4 July 2025, she will turn 101 years old.

Starring Kem Dibbs as Buck Rogers and Lou Prentis as Wilma, and produced and directed by Babette Henry, the show began at 7pm on 15 April 1950. Each show had a budget of $5,500 and was filmed live to air. It was rated fifth for children’s shows in September’s issue of Billboard, behind Cactus Jim, Howdy Doody, Super Circus and Lucky Pup. It was aired in fifteen cities and reached 439,000 houses for a 9.5 share of the market.

Although websites and books insist that Earl Hammond was the first Buck Rogers on television, contemporaneous reviews clearly state that Kem Dibbs had that role. As the early episodes no longer exist, it is difficult to confirm who stepped out on that first night.

The cast and crew threw a party after the first show was screened. In what might have been a forerunner for what was to come, The Buffalo News reported that the party turned into an all out brawl which needed police to attend to break it up.

The reviews weren’t the best.

Success of such a show will depend on the scripting and writer Gene Wyckoff showed sufficient initiative on the opener to indicate he'll be able to turn out the amazing" stories in stride. Apparently with the N.Y. water shortage in mind, although he never referred to it, Wyckoff spun his tale about a couple of "tigermen" from the planet, Mercury, who came up with a horrendous scheme to drain all the water off the earth to gain control of the universe. Only trouble with the script, probably because of video's still-limited facilities, was that it was played entirely on interior sets. Lack of exteriors cramped the space mood it should have had.

Variety, 19 April 1950

The TV version of Buck Rogers is not too promising if the first show is any criterion. In radio the audience could depend on its imagination to take it winging into space. On TV the audience is compelled to see what stacks up as a cheap production geared to a limited budget. Titled Piper of Doom, the story had Rogers taking a space trip to get pictures of the sun, only to be nearly burned alive by a convict (who played the flute, yet).

Hampered by the script, the acting never got off the ground. As Buck Rogers, Kem Dibbs looked the part, but otherwise was only adequate. Lou Prentiss was his properly hysterical female companion unnerved by the musical villain. As the brainy Dr. Huer, Harry Sothern had trouble remembering his lines. The real villains of the show were the commercials. They made the program into a cliff-hanger, to be continued after the next commercial. There were four in number and they repeated that Mounds are fresh, fresh, fresh.

Billboard, 13 May 1950

The show ran for thirty six episodes over 1950 and into 1951. Three actors were used as Buck – Kem Dibbs, Earl Hammond and Robert Pastene. The show was wiped, only a few episodes exist today.

In a surprise move, Dille sold the exclusive rights to Buck Rogers, barring the newspaper strip, to a consortium of businessmen from Hollywood. The four men, millionaire sportsman Robert S. Howard, paper mill owner Louis J. Meunier, motion picture attorney Max Gilford and movie and television producer Bert D’Armand, then formed three separate companies, each designed to exploit the rights in their chosen field. The companies were the Buck Rogers Merchandising Company, Buck Rogers Theatrical Productions, Inc and Buck Rogers Television Productions, Inc. The exact cost of the deal is unknown, but newspapers at the time reported that ‘several million dollars in rights and royalties’ were involved.

The plan was for the consortium to open offices at the Hal Roach Studios and begin casting for a twenty-six episode television series and a full length feature film to follow. A new radio show was also being talked about.

None of them would eventuate and the rights would eventually come back to Dille. In 1954, Dille would renew his trademarks.

On 10 September, 1957, John Flint Dille died. Aged seventy two, he died after an operation in Evanston, Illinois. Newspapers reported him as the sole creator of Buck Rogers, with a few calling him a cartoonist on the title. Editor and Publisher, a publication that should have known better, wrote Nowlan out of the creative process and stated that Dille created the strip with Calkins. By now Nowlan, dead for seventeen years, was forgotten. With the passing of John F. Dille, his son, Robert C. Dille would take control of the National Newspaper Service and the John F. Dille Company.

More upheaval came in June 1958 when Rick Yager quit the newspaper strip. Yager wasn’t happy with the direction of the strip, and the feeling was mutual. ‘Too much editing, too much criticism. I just couldn’t create any more,’ Yager told Time Magazine.[4] Robert C. Dille wasn’t upset., saying simply, ‘We’re happy he quit.’[5]

The end had been coming for a while. Dille insisted that Yager supply his ideas for the strip well in advance and to tone down the science fiction aspects. The strip had to be rooted in reality. ‘We argued and talked about it,” Dille was quoted as saying, ‘and, believe me, there are times when a syndicate president would like to put an artist into orbit.’ Yager wasn’t looking back. He was negotiating with three syndicates for a new science fiction strip that he hoped would put Buck Rogers in the shade. Plus, with the launch of Sputnik, Yager felt that a reality based Buck Rogers was obsolete. ‘Buck Rogers’ day is here,” explained Yager. ‘So now a fellow has to think up things the scientists haven’t got yet.’[6] The strip that Yager developed was The Imaginary Adventures of Little Orvy. It didn’t last long. Replacing Yager would be Murphy Anderson.

When Dille published The Collected Works of Buck Rogers, he was more gracious with his words about Yager. ‘Rick Yager - as fast as he was talented - rendered Buck Rogers characters in a forceful, vital manner, employing heavy, self-assured strokes for his delineations. His drawings virtually breathe. He was one of the few artists capable of making a transition from the grotesque 'cartoon' style of the late Twenties and early Thirties to the true 'illustration' style popularized by Terry and the Pirates and other strips. Many of Yager's contemporaries developed an overly slick technique that transformed drawings into little more than photographs drained of incipient movement and life. Not Rick.’[7]

Anderson remained on the strip until April 1959, after which he was replaced by George Tuska. Tuska would remain with the strip until its demise in 1967. Writing the strip for the remainder of its life would be Jack Lehti, Howard Liss, Fritz Kleiber and Ray Russell.

[1] The Comics Feature #10, July 1981

[2] Theresa’s daughter was also name Theresa, however she also spelt her name as Teresa. I will use the latter name to denote Philip’s daughter throughout this series.

[3] Not to be mistaken for former Stan Lee Media, Inc executive Peter Paul.

[4] Passing the Buck, Time Magazine, 30 June 1958

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] Dille, Robert C., editor. The Collected Works of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (New Revised Edition, 1977)